Climate Refugees: A Story of Classification, Bureaucracy, and Recognition

The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States published a study this May predicting the next 50 years will leave 1 to 3 billion people outside of the climate conditions that have been considered habitable for humans over the past 6,000 years. The findings of the study portend that a substantial part of the world population will be exposed to temperatures higher than anywhere found on the planet today. This will leave entire communities in conditions unsuitable for life-sustaining activities such as agriculture and without access to basic needs like clean water.

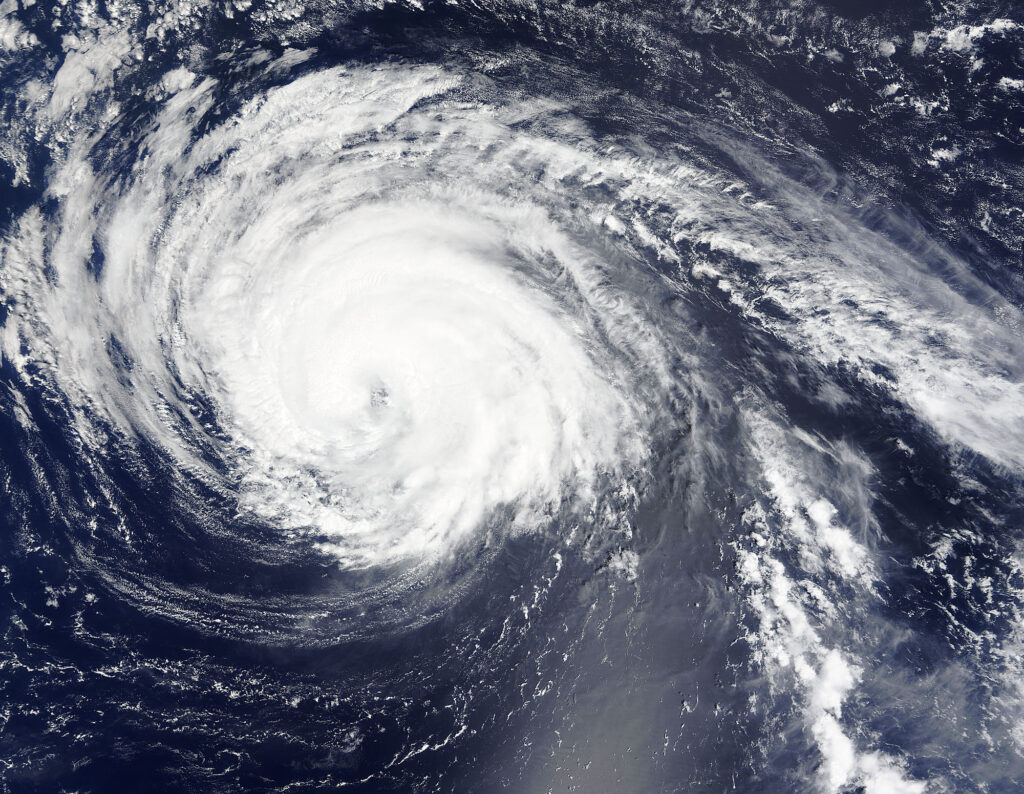

While mitigation efforts remain an important part of lessening the global impact of climate change, many parts of the world have been left vulnerable to its effects for years. With many countries already experiencing immediate threats, including several small Pacific Island nations such as Kiribati and Tuvalu, the urgency of the matter is clear. The geographical position of these states makes them most susceptible to rising sea levels and more frequent and higher intensity cyclones, both phenomena that scientists have consistently said are the first indicators of what will continue as part of a dangerous upwards trend of extreme weather patterns on a broader global scale. Extreme weather events, when combined with the vulnerable geography of such nations, also make internal climate migration impossible, as the effects of climate change are all consuming. This means that citizens of such states will be forced to flee to other nations. Yet, as of now climate refugees are still not recognized within any international legal framework.

Currently, the basis of all international law concerning the rights of the displaced comes from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, which defines a refugee as “someone who is unable or unwilling to return to their country of origin owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group, or political opinion.” The Convention explicitly indicates that this definition should be accepted as encompassing all refugees, not specific groups (as previous frameworks had done). The UN Refugee agency as a whole claims to protect refugees by intervening should states fail to uphold the core principle of non-refoulement, as is outlined in the 1951 Convention, which “asserts that a refugee should not be returned to a country where they face serious threats to their life or freedom.”

Calls for international recognition and more comprehensive protections for climate refugees have been made by scientists and human rights activists alike for years. The UN continues to reiterate their firm stance that climate refugees are not recognized by international law and explicitly articulates that “the term ‘climate refugee’ is not endorsed by UNHCR.” The UN has defended this position in the past by saying that the climate crisis will first have an impact on migration patterns in the form of internal displacement but, as we now know, this is impossible in the most vulnerable areas like Pacific island nations. In fact, the UN reported one of its first climate-related asylum claims back in 2015, when a citizen of the Pacific island nation of Kiribati was deported from New Zealand following a denied asylum application. In response to the 2015 case, the UNHCR made a statement in which they “determined that countries cannot deport people who have sought asylum due to climate-related threats.” However, without substantial amendments to existing refugee protections, this statement holds very little weight and can easily be worked around by governments seeking to avoid upholding the judgement.

Climate refugees are not the first to expose the inadequacies of current legal frameworks for asylum seekers. Policies such as Canada’s Safe 3rd Country Agreement have long drawn criticism for exploiting the ambiguity of existing international frameworks in a way that puts the rights of the displaced in jeopardy. Now more than ever, because of the urgency and scope of the climate crisis and the immediate danger it poses to the livelihoods’ of those affected by it, the UN must answer calls for amending the clearly inadequate current international requirements for determining refugee status. Even relatively conservative estimates predict asylum applications to increase globally, on average, by 28 per cent by the end of the century (which would mean at least 98,000 additional asylum applications per year). This comes along with scientific studies continuing to confirm a strong correlation between climate change, extreme weather events, and this accelerated increase in asylum cases.

While the UNHCR has made several statements in acknowledgement of the severity of the climate crisis as well as its implications for human migration patterns on a global scale, in the years following their first climate-related asylum claims, the agency has only adjusted frameworks in the form of unsubstantial goal-setting such as its recently adopted Global Compact on Refugees (2018). This Compact asserts that its objectives are to “(i) ease pressures on host countries; (ii) enhance refugee self-reliance; (iii) expand access to third country solutions; and (iv) support conditions in countries of origin for return in safety and dignity”. Beyond the fact that these objectives are clearly intended to excuse larger, more wealthy, and less vulnerable countries of any accountability for aiding in a global humanitarian crisis, the Compact also states that it is by no means legally binding, once again providing wealthy states with an easy loophole through which they may evade responsibility.

The UN is blatantly ignoring cries for help from small, poor, and at-risk states both by blindly relying on the false hope that internal displacement will occur before any international refugee crisis, as well as adopting frameworks like the Global Compact on Refugees. By doing so, the UN is creating more ways for larger and wealthier states to avoid taking an active role in protecting the most vulnerable in the ever worsening climate crisis, thus adding to the many ways in which the climate crisis will continue to disproportionately impact already marginalized groups. The bureaucratic structure of intergovernmental organizations like the UN along with the legal language of official documents obfuscating comprehensive understanding of available protections makes it nearly impossible for asylum seekers to seek individual help. Because of the harmful nature of such structures, the UN is able to leave unchanged a system which allows both their own agencies as well as other governments to forgo their responsibility to uphold the rights of vulnerable populations with little to no scrutiny. The UNHCR must fully reevaluate existing international refugee protections, not just through the addition of meaningless provisions to placate critics, but to ensure the rights of the displaced under all circumstances and in all parts of the world while simultaneously holding less vulnerable states accountable for upholding the principles of non-refoulement. Failure to do so will undoubtedly result in a global humanitarian disaster, and the UN will be to blame.

Featured image: “Climate change = more climate refugees.” by John Englart licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

Edited by Selene Coiffard-D’Amico