Coercive Diplomacy and North Korean Denuclearization

Trump and Kim shake hands at the historic summit in Singapore on June 12th of this year. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Trump_and_Kim_shaking_hands_in_the_summit_room.jpg

Trump and Kim shake hands at the historic summit in Singapore on June 12th of this year. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Trump_and_Kim_shaking_hands_in_the_summit_room.jpg

Two Decades of Failure and Broken Promises:

Chairman Kim Jong-Un proclaimed North Korea’s newfound nuclear status during his New Year’s Speech of 2018, thus marking the failure of two decades of US policy towards non-proliferation. President Clinton utilized dialogue and engagement, Bush sought a confrontational approach by labeling the country as apart of ‘axis of evil’, while Obama’s efforts were termed a malign neglect owing to lack of any substantive effort to denuclearize North Korea.

President Trump’s recent Singapore Summit statement towards denuclearization is unlikely to succeed after examining Pyongyang’s record. The DPRK broke the 1985 NPT (Non-Proliferation Treaty), 1992 Joint Declaration on the Denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula, 1994 Agreed Framework towards denuclearization, 2005 and 2007 pledge to denuclearize, and 2012 agreement to suspend all nuclear activities. Therefore, the DPRK’s pledge at the Singapore Summit is dubious, indubitably so due to the dearth of details regarding how denuclearization will occur.

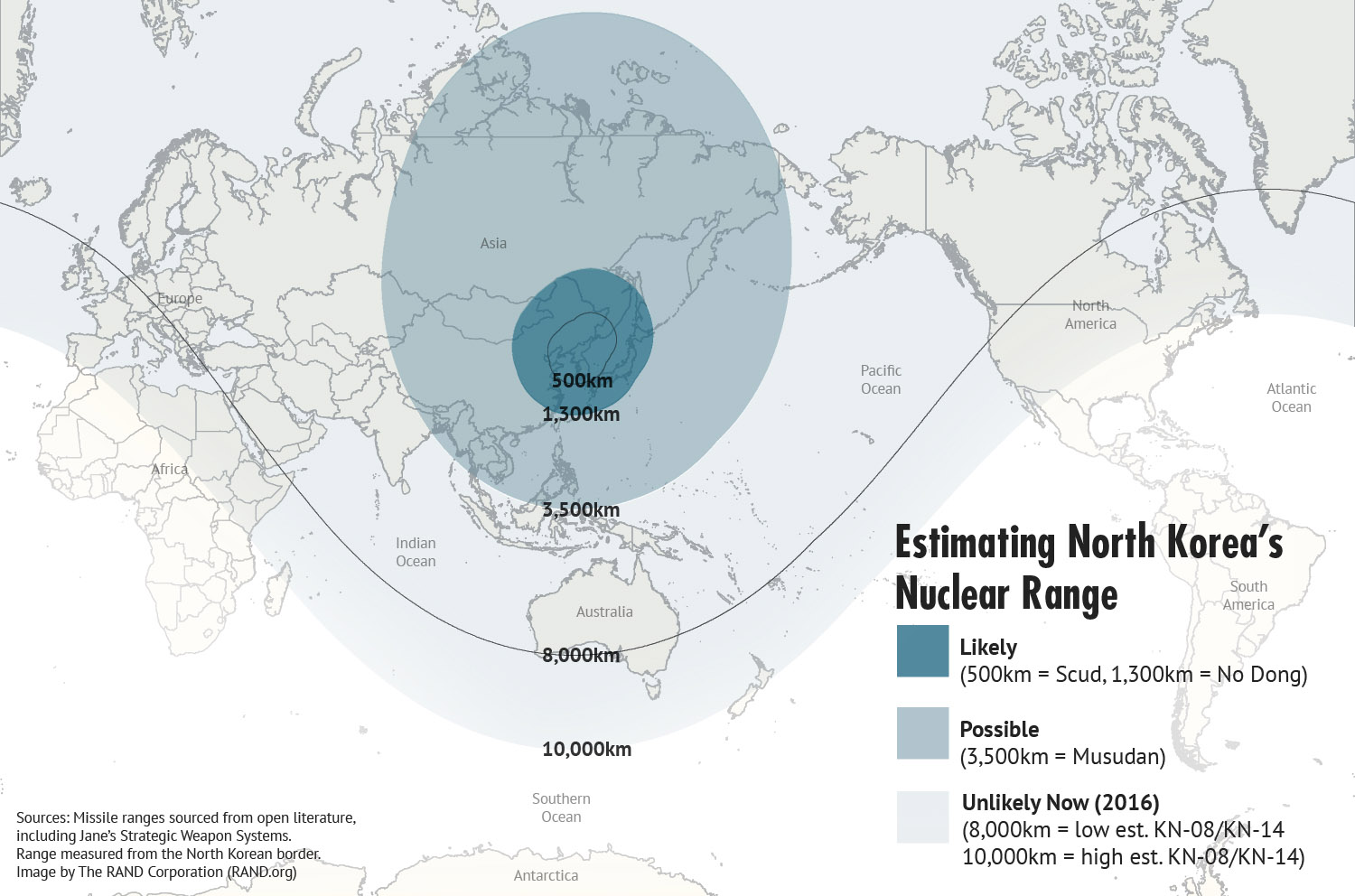

The DPRK will renege on denuclearization due to underlying security concerns, i.e. to deter hostile regime change by the US alliance in tandem with South Korea, known as US-ROK. While Pyongyang’s military doubles that of the US-ROK alliance, their equipment is antiquated. The US-ROK, meanwhile, is a modern and potent force, with the balance of power in their favour and this reality unlikely to change by conventional means. Thus, Pyongyang sought nuclearization due to its effect as a great equalizer, whereby nuclear weapons permit even the smallest states to achieve deterrence against a powerful adversary, permitting the DPRK to maintain parity through the power of the atom.

The Danger of North Korea’s Nuclearization:

Pyongyang has a history of providing sensitive nuclear assistance to rivals of the United States, e.g. Libya and Syria, thus imposing strategic costs on Washington by proliferating their rivals. In addition, North Korea has historically provided nuclear assistance to despotic regimes, problematic as this would permit these regimes to violate human rights without fear of humanitarian intervention.

Pyongyang’s nuclearization is a threat to US allies, who may respond by seeking their own nuclearization to the detriment of the NPT. South Korean public opinion increasingly favours nuclearization; however, this may prompt a North Korean preventive attack due to their military-dominated government. This is alarming due to the military’s preponderance towards preventive attack, which runs a high risk of escalating into a regional conflict.

What Should the Response be to North Korea’s continued nuclearization?

- Military strikes: Military strikes can be conducted to neutralize Pyongyang’s nuclear deterrence. However, South Korean public opinion is opposed to such action, and their consideration matters as any escalation into regional conflict will occur in their homeland. In addition, poor intelligence regarding the whereabouts of Pyongyang’s arsenal, coupled with their utilization of mobile road launchers, make it difficult to attain complete destruction.

- Sanctions: Sanctions would pressure Pyongyang to denuclearize in exchange for ean conomic reprieve. However, this is unlikely to succeed as North Korea weathered two decades of sanctions in order to nuclearize. In addition, Beijing is loathe to isolate Pyongyang due to fears of regime collapse resulting in the reunification of a US-aligned Korea; this concern predicated Beijing’s intervention in the Korean War and likely to remain.

- Coercive Diplomacy: Washington must work with allies to demonstrate to Pyongyang that further provocation will be matched, and that the regime security sought by Pyongyang can only be attained through denuclearization. Diplomatic overtures should include China to permit Beijing to assuage Pyongyang’s security concerns. Should this policy fail, coercive diplomacy will permit Washington to contain Pyongyang, prevent the export of sensitive nuclear assistance, signal US commitment to Asia, and thereby reassure allies and prevent their own nuclearization.

- A policy of coercive diplomacy is predicated on Pyongyang’s nuclearization to deter regime change against the overwhelming military might of the US-ROK alliance. Therefore, permitting a policy where Pyongyang’s regime security is contingent with denuclearization, as continued nuclearization will lead to continued US containment and escalating pressure through increased US commitment.

How to Conduct Coercive Diplomacy:

Diplomatic overtures to Pyongyang must seek the formulation of a plan towards denuclearization. Pyongyang would be compelled to negotiate because Washington with regional allies would apply military pressure, and enhance sanctions to prevent nuclear export and cut off revenue. Secondary sanctions may be needed against China to demonstrate US resolve to Pyongyang, and would aid current Sino-US trade disputes. Increased commitment in the region through an additional Carrier Battle Group, B2 bombers, and increased US-ROK military exercises will demonstrate US resolve. The deployment of the THAAD ballistic missile defence system will limit the effectiveness of North Korea’s nuclear weapons, and in conjunction with increased sanctions and military commitment, demonstrates US resolve to Pyongyang.

Pyongyang must understand that regime security can only be attained through denuclearization, and that a gradual path to denuclearization will be reciprocated through the easing of pressure against Pyongyang. Once dialogue is attained, Beijing must be included as their security guarantee towards Pyongyang is required to provide Pyongyang’s regime protection. Should denuclearization fail, coercive diplomacy will permit Washington to contain Pyongyang, while reassuring US allies to prevent their own nuclearization.

Despite fears that Pyongyang may retaliate to increased sanctions and US pressure through a preemptive attack, this is highly unlikely as it would provoke the very regime change they seek to prevent. In addition, Beijing can be induced to work alongside Washington despite ongoing trade disputes by utilizing their fear of a nuclear Japan, as stabilizing the Korean Peninsula and denuclearizing North Korea will stymie a potential cause for Japanese proliferation. As while Japan is unlikely to nuclearize any time soon, Beijing greatly fears the potential likelihood.

Finally, a policy of coercive diplomacy provides contingency plans should denuclearization fail, as it permits Washington to contain and punish Pyongyang; meanwhile, a failed military strike is likely to provoke military retaliation, and failure of sanctions provides no means to apply continued pressure against Pyongyang.

Edited by Andrew Figueiredo