Colombian Exceptionalism: The Unusual Absence of a “Left Turn” Amid Continued Colombian Conservatism

The Palacio de Nariño, residence and workplace of the President of Colombia.

The Palacio de Nariño, residence and workplace of the President of Colombia.

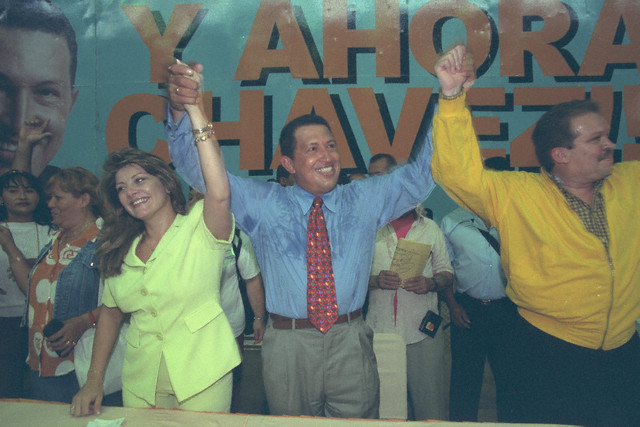

We all know about the doctrine of “American exceptionalism”—that the United States has been uniquely molded by the values of liberty, equality, representative democracy and laissez-faire economics—but have you ever heard of “Colombian exceptionalism?” Likely not. Return for a moment to 1982, at the onset of the Latin American debt crisis. With countries unable to pay back debts accumulated during industrialization to international creditors, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) consequently provided much of Latin America with the necessary funds through structural adjustment programs (SAPs). These conditional loans reoriented Latin American economies towards a supply-side economic model characterized by austerity, privatization, and reduced social services. This pro-market reform was far from a resounding success. Not only was it largely ineffective in mitigating economic instability, but it also visibly increased socioeconomic inequality and poverty throughout Latin America over the next two decades. In the case of Colombia, GDP growth fell below 1% in 1998 before plummeting into one of the worst recessions in the continent by 1999, as GDP fell by another 4.5%. The situation across the rest of the region proved equally untenable. Plagued by popular disapproval over growing poverty and economic stagnation, the pro-IMF Caldera government was ousted in Venezuela in favour of Hugo Chavez in the 1998 elections, realigning the entire Venezuelan political system and marking the rise of mainstream leftism in Latin America.

Although much of Latin America saw the commonization of socialist rule in the early-mid 2000s in response to the failure of the IMF’s agenda, no “left turn” ever swept Colombia. Rather, the presidency of the conservative Álvaro Uribe (2002-2010) continued to carry out neoliberal economic policies in line with international economic institutions like the IMF and the World Bank. Even into the present-day, subsequent governments, including the incumbent Duque administration, have adhered to pro-business fiscal conservatism. With this in mind, why has the Colombian right remained so unshakable for so long in contrast to the rest of Latin America?

The Effects of Plan Colombia

Perhaps unsurprising given the history of American intervention in Latin America, the United States has played an essential part in shaping political outcomes in Colombia through “Plan Colombia,” an aid package first initiated under the Clinton administration. From 2000 to 2015, the U.S. government contributed $10 billion USD to strengthen both the Colombian government’s counter-narcotics program and its military campaign against the left-wing Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) insurgency. The restoration of law in FARC-controlled territories was deemed crucial to the United States’ success in the War on Drugs, as the revolutionaries were mostly concentrated in areas of heavy coca cultivation and utilized drug trafficking as a source of funding. As part of Plan Colombia, the Direction Antinarcoticos, a subset of the Colombian national police force, began an aerial fumigation program spraying thousands of hectares of farmland in Colombia’s coca-growing provinces, causing cocaine production to falter and the FARC to increasingly lose ground alongside it.

Although the plan succeeded in both undercutting cocaine production and the accompanying insurgency, it has left behind enduring ramifications for the left in Colombia. Going back decades, the Colombian army has been documented collaborating with right-wing, anti-Marxist paramilitary support groups who have been responsible for roughly 75% of human rights violations in Colombia’s civil conflict.1 Although there were calls from human rights organizations during House-Senate negotiations in the U.S. to “root out army complicity with paramilitaries” before granting funding to the plan, President Clinton waived five of six human rights concerns put forward by these groups, deeming Plan Colombia to be in the “national security interest.”2 Consequently, these concerns rang true, for right-wing paramilitaries were emboldened by Plan Colombia, leading to an increase in acts of violence, particularly against supporters of the perceived “left.”

Although the left has not won office in Colombia, it cannot be stated that left-wing political and social movements outside the FARC do not exist at all. Movements like the Marcha Patriótica have emerged, which have denounced the state for promoting megaprojects and extractive industry—framed as “the forces of global capital assaulting the disenfranchised peoples of the Colombian countryside.”3 The Marcha Patriótica has also sought to improve social justice in Colombia by advocating for the socioeconomic rights of “traditionally excluded sectors of the population” such as peasants, women, blacks, indigenous people and sexual minorities. Given this, the issue at hand is that right-wing paramilitary groups, emboldened by Plan Colombia, have continued systematically targeting non-violent leftist organizations like the Marcha Patriótica and their supporters. For example, 166 members of Marcha Patriotica have been killed by the radical right since the foundation of the movement. Afro-Colombian organizations, seen as sympathetic to leftist groups like the Marcha Patriótica due to mutual concerns over black rights, have fallen victim to similar escalations of violence. In 2012, the leader of AFRODES (an association representing Afro-Colombians displaced by the FARC conflict), Miller Angulo Rivera, was assassinated by right-wing paramilitaries. In 2011 alone, twenty-nine black union leaders were murdered.4 In brief, American support in Plan Colombia has effectively trickled down to empower right-wing counter-insurgents with documented ties to the Colombian government, who have since intensified violence against the Colombian left. This violence frequently extends to members of the black community linked by guilt of association, creating a culture of fear around being identified as a leftist.

Colombian Conservatism and Class Linkages

The parties of the post-Chavez ‘left turn’ in Latin America, adhering to principles of economic redistribution and social equality, have traditionally drawn their support from groups of lower socioeconomic standing. This can be taken a step further, as certain (but not all) political leaders of the Latin American left turn have utilized populism to forge direct links with the poorer masses to garner political support. However, the conservative Álvaro Uribe, who watched as the left swept his Latin American neighbours, remained safely in power neither appealing to the lower classes nor utilizing populism.

The first of his 100 points in his 2002 ‘Democratic Manifesto’ prioritized the middle class above others. Therein, he famously proclaimed that “I dream of a Colombia with a predominant democratic middle class, tolerant, supportive and respectful.” Although Uribe did not give precedence to the socioeconomically disadvantaged, he did address some of their concerns. For example, in his 2002 campaign, Uribe swore to expand education to accommodate 1.5 million more students and to construct 100,000 new low-cost housing units per year.5 Nevertheless, these promises were not unusual in Colombian politics, and were subsequently followed by calls for government austerity.6 Uribe additionally disavowed populism in his 2002 election manifesto. He stated, “I offer a serious, effective government, not a miraculous one.” Uribe equally criticized demagogy and populism, seeing unrealistic campaign promises as unconducive to democratic credibility. Unlike Latin American figures of the left like Chavez (Venezuela) and Morales (Bolivia), Uribe refrained from using emotionally charged language that would have cast himself as the leader of ‘the people’ waging war against the forces of the establishment.

With this in mind, why did Uribe have little opposition from the left while in power? The answer is simple: despite the fact that he forsook populism and largely appealed to the middle class, Uribe strategically reined in the Colombian left by winning over their usual base: the socioeconomically disadvantaged. He achieved this by remaining steadfast in his militaristic stance against the FARC, which resonated with a populace exhausted with guerrilla violence.7 Poorer Colombians, who had formed the bulk of those harmed by the FARC guerrillas, welcomed many of Uribe’s hardline security measures. These notably include his promise to strengthen state security by doubling the number of soldiers, and to establish ‘Days of Recompense’ by which the government would pay citizens who had helped state security forces prevent a terrorist act or capture terrorist suspects.8 Poorer Colombians came to see him as the “rare politician who had the backbone to confront the guerrillas.”9

Uribe’s widespread support from the lower rungs of society also benefited from the “context of the times.” In the late 1990s, Colombia’s decades-long conflict with the FARC was becoming progressively more violent, with 7,500 mostly poorer Colombians being killed each year.10 In essence, it was the loyalty of the poorer classes to the strongly anti-FARC and conservative Uribe that was crucial in stopping a leftward turn from reaching Colombia. This strategy has largely been carried into the present-day by President Duque, who secured impressive electoral results in 2018. Campaigning on a program of truth, justice, and reparation, through which victims of the Colombian civil conflict were placed at the center of peace negotiations with the FARC, Duque won by double digits over his rival Gustavo Petro, Mayor of Bogotá and a former leftist guerrilla.

Colombian Exceptionalism No More?

For all the Colombian right’s apparent invincibility, there are telltale signs that its monolithic position is rapidly fading. Most importantly, Duque’s administration has utterly failed to sway young Colombians. Unlike older voters who remember the violence of the late 1990s more vividly, anti-FARC policies have not been sufficient in capturing the youth vote, of whom 80% express a negative opinion of Duque. As this demographic increasingly comes of age and displaces the older voter base, their vastly different concerns may see the “pink tide” of 21st century Latin American leftism fall upon Colombia at last.

Featured Image: Fachada del Palacio de Nariño by Juanjo70000 is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Edited by Anthony Kuan

Citations:

- 1. Justin Delacour, “Plan Colombia: Rhetoric, Reality, and the Press,” Social Justice 27, no. 4 (2000), 63.

- 2. Ibid.

- 3. Nick Morgan, “The Antinomies of Identity Politics: Neoliberalism, Race and Political Participation in Colombia,” in Cultures of Anti-Racism in Latin America and the Caribbean (London: University of London Press, 2019), 42.

- 4. Ibid.

- 5. John C. Dugas, “The Emergence of Neopopulism in Colombia? The Case of Álvaro Uribe”, Third World Quarterly 24, no. 6 (2003), 1126.

- 6. Ibid.

- 7. Ibid, 1134.

- 8. Ibid, 1128.

- 9. Ibid.

- 10. Ibid.