Concerns about Hong Kong’s Media Rights

Flickr by inmediahk

Flickr by inmediahk

On the day of Hong Kong’s handover from the British to the People Republic of China, Deng Xiaoping, the leader of the Chinese government then, declared the constitution of “One country, two systems” that will last for 50 years. He accepted Britain’s term in retaining Hong Kong’s currency, legal and parliamentary system and political freedom, which constitutes the Basic Law. Under the protection of the Basic Law and the principle of “One country, two systems”, Hong Kong arguably enjoyed the privilege of political independence from the Chinese government since 1997 during which freedom of expression was not suppressed. This has allowed local media and news to thrive without censorship from Beijing, while allowing Hong Kong to be a special liaison between the international news media and Mainland China. Nevertheless, as time passed, the Chinese government has gradually interfered with Hong Kong’s autonomy, with increasing intensity in recent years triggered by public protests especially the universal suffrage discussion and the “Umbrella revolution”.

The Copyright (Amendment) Bill, the so-called “Internet (Cyberspace) article 23”, arguably suppresses “Internet freedom” in forms of artwork in Hong Kong. Some amendments put forth by the government was to expand the scope of intellectual property protection. The public was skeptical about the bill, particularly with its vague nature accounting exemptions from the Bill. During the public consultation period, the online community and public groups, such as the Concern Group for Rights of Derivative Works and Concern Group for Rights of Derivative Works, raised voices against the amendments introduced. While the Hong Kong government strongly argues that the amendments are to provide better protection to the original creators, the public raises concerns regarding the political motivations behind. Internet parody, satire, caricature and pastiche were always part of Hong Kong’s political art culture. Howard Lam Tsz-kin, spokesman of the Internet Freedom Concern Group, described derivative works about current politics as “a mobilizing force in society” and that people can “understand politics more easily” in form of art. Derivative works stimulate political discussion, and provide a platform for the citizens to express their political stands or views on the government. Given the current political circumstances, the vague legal wordings on the Bill can potentially censor freedom of expression to the liking of the government.

Individuals working in news companies are also affected by Beijing’s increasing threat to freedom of speech. Local news companies and journalists are pressured to censor their stories and article. According to a report published by the PEN American Center, a New York-based writers’ group, “many media owners and advertisers in Hong Kong hold big commercial stakes in mainland China and have increasingly tailored their reporting, or advertising orders, to please the authority”, of which is the Beijing government. This degrades the integrity of journalists and news companies. Journalists and news companies should uphold the objectivity of their reports. Nevertheless, there is a spread of fear and insecurity among Hong Kong journalists; the Hong Kong Journalists’ Association states that there has been an increase incident in “physical attacks against journalists, staff changes, self-censorship and financial pressures”. The most violent assault was in 2014. Kevin Lau, the former chief editor of Ming Pao Daily News, was heavily injured from stabbing by two Mainland Chinese assailants. During his tenure as the chief editor of Ming Pao, Kevin Lau has allow investigation stories about the relationship between Hong Kong and Mainland China to be published. In fact, according to Sham Yee-lan, the chairwoman of the Hong Kong Journalists Association, there were more than 28 attacks on journalists in 2014 during street protests. This is a reflection of not only the journalists’ personal safety heavily affected, but also a psychological threat to the integrity of Hong Kong media to encourage self-censorship.

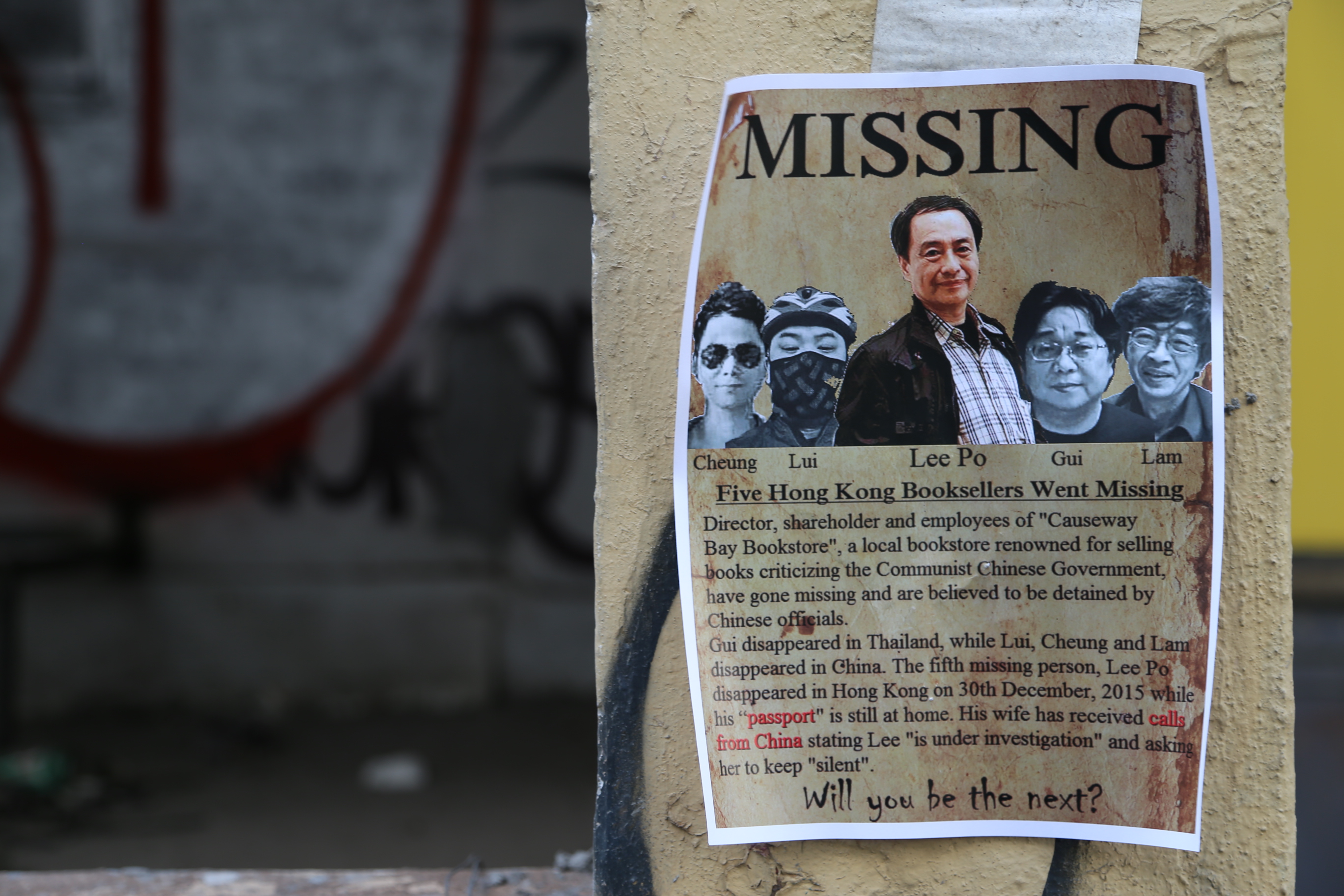

The freedom of book publication and circulation has also been threatened with the infamous incident of five Hong Kong booksellers disappearing early in 2016. Mighty Current Media Company Limited is known for publishing scandalous political books mainly about the Chinese government and officials – books that are forbidden in the Mainland China. Five people associated with this series have all disappeared within a short period of time, and there is strong suspicion about the involvement of the Mainland Chinese authority. Although the Hong Kong chief executive, C. Y. Leung, claimed that there is “no indication” that these disappearances were associated with the Chinese security agents, Hong Kong public believes otherwise. There is an overall distrust of the government, both the Beijing and Hong Kong government, which heightens the fear of information suppression and control over access to knowledge.

Overall, the Hong Kong media has been governed by fear and potential legal limitation to freedom of expression. These limitations and psychological censorships can threaten the freedom of information access Hong Kong citizens enjoy, and impose fear on the population, with a breach in the journalists’ integrity and media rights. The city where active criticism of the government is suppressed and discouraged and person safety threatened indicates the retrogression of its political development since the handover.

Citations

- Baldwin, C. (2015). Hong Kong journalist association says press freedom deteriorating. Reuter. Retrieved from http://www.reuters.com/article/us-hongkong-pressfreedom-idUSKCN0PM0LP20150712

- Cheng, K. (2015). Gov’t says new copyright law will not restrict speech amid concerns of parody ban. Retrieved from https://www.hongkongfp.com/2015/12/03/govt-says-new-copyright-law-will-not-restrict-speech-amid-concerns-of-parody-ban/

- Chris Buckley, M. F. (2015, 16 January 2015). Press Freeom in Hong Kong Under Threaat, Report Says. New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2015/01/17/world/asia/press-freedom-in-hong-kong-under-threat-report-says.html

- Liu, C. and Gray, M. (2012, 25 July 2012). Hong Kong sellers profit from Beijing’s ‘forbidden’ books. CNN. Retrieved from http://edition.cnn.com/2012/07/25/business/china-forbidden-books/

- Hui, M. (2014). As China’s control grows, Hong Kong media freedoms recede. Retrieved from http://www.poynter.org/2014/as-chinas-control-grows-hong-kong-media-freedoms-recede/251062/

- Hunt, K. and Watson, I. (2016, 6 January 2016). UK, Sweden express concern over missing Hong Kong booksellers. CNN. Retrieved from http://www.cnn.com/2016/01/04/asia/hong-kong-china-missing-booksellers/

- Lau, S. (2016, 02 March 2016). Hong Kong copyright bill debate enters final 48 hours after latest compromise bid fails. South China Morning Post. Retrieved from http://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/politics/article/1919969/hong-kong-copyright-bill-debate-enters-final-48-hours-after

- Lian, J. Y. (2015). Why we must not ignore cyber article 23? (translated to English). Retrieved from http://www.ejinsight.com/20151208-why-we-must-not-ignore-cyber-article-23/

- Oshiro, S. (2014). Hong Kong journalists, students rally against intimidation after knife attack on editor. Retrieved from http://www.poynter.org/2014/hong-kong-journalists-students-rally-against-intimidation-after-knife-attack-on-editor/241493/

- Pen. (2015). Threatened Harbor – Encroachments on Press Freedom in Hong Kong. Retrieved from http://www.pen.org/sites/default/files/PEN-HK-report_1.16_lowres.pdf

- Tsoi, G. (2011, 1 September 2011). Copyright Crackdown. Hong Kong Magazine.