COVAX: The Challenges of Equitable Vaccine Distribution

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and the Canadian government made headlines in early February when they announced that Canada was going to acquire nearly two million of the first coronavirus vaccines to be distributed by COVAX, a global vaccine acquisition program serving over 160 countries. As the only G-7 country to be receiving vaccines in this first shipment — originally intended for lower-income countries — Canada has been accused of “double-dipping” by acquiring additional vaccines to supplement its already record-breaking commitment to buy over 400 million doses for a population of merely 37 million. As such, Canada has drawn criticism for taking vaccines from an already limited supply for the world’s poorest populations. While much of the media’s focus has been on Canada’s future acquisition of these vaccines, it is worth better understanding what exactly COVAX is, how it came to be, and its potential weaknesses as a tool for equitable vaccine distribution.

What is COVAX?

Jointly founded in April 2020 by the World Health Organization (WHO), the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI), and the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization (Gavi), COVAX was initially meant to “support the research, development and manufacturing of a wide range of COVID-19 vaccine candidates, and negotiate their pricing.” The COVAX “facility” does this by pooling the financial resources of many countries in what is called an Advanced Market Commitment (AMC). This AMC incentivizes pharmaceutical companies to make risky investments in the development of new vaccines and manufacturing facilities.

To participate in the program, richer “self-financing” countries can request vaccine doses for 10 to 50 per cent of their population, and pay the corresponding price. Meanwhile, low and middle-income countries have their contributions subsidized by self-financing countries and donor organizations. Notable private donors include the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation ($156 million USD) and TikTok ($10 million USD). As vaccines become approved, COVAX will distribute them proportionally to participating countries until a maximum of 20 per cent of the population of each country is vaccinated. It is believed that vaccinating one-fifth of the population will help bring the acute phase of the pandemic to an end. Once every member country has reached 20 per cent vaccination, then the COVAX facility will continue to distribute the remaining doses.

For higher-income self-financing countries, such as Canada, COVAX is meant to serve as an insurance policy should their own bilateral agreements with pharmaceutical companies fall through. Having ideally established their own vaccine acquisition programs, the expectation is for self-financing countries to let poorer countries draw vaccines from the pool first, or at least earlier on. Meanwhile, for lower and middle-income countries, COVAX is quite literally the only viable option to ensure vaccine access. So why would the governments of higher-income countries finance the acquisition of vaccines for foreign populations? Beyond humanitarian concerns, providing equitable access to vaccines is the best way to end the COVID-19 pandemic once and for all and fully reopen the global economy. Moreover, recent studies demonstrate that inequitable access to vaccines will significantly harm the economies of higher-income, fully-vaccinated countries.

COVAX’s weaknesses

COVAX is a unique tool that is driving the charge for equitable access to COVID-19 vaccines for all populations. However, its success relies on a number of factors that are not guaranteed. Most notably, the program relies on self-financing countries being able to coordinate their own deals with manufacturers while using COVAX merely as an “insurance policy.” Nevertheless, when self-financing countries struggle to acquire vaccines independently and begin to claim their “insurance,” COVAX’s vaccine distribution becomes less and less equitable. Due to Canada’s lack of biomanufacturing capacity relative to other developed countries, it has come under increasing domestic pressure to rapidly import more vaccine doses. Consequently, Canada has resorted to claiming vaccines from COVAX’s first distribution. Although Canada is entitled to these vaccines given its initial financial commitment, as explained above, the first shipment was intended for lower-income countries. As high-income countries aim to vaccinate their own populations as fast as possible and “vaccine nationalism” takes hold, COVAX contributors may be more and more inclined to acquire doses initially intended for lower-income countries.

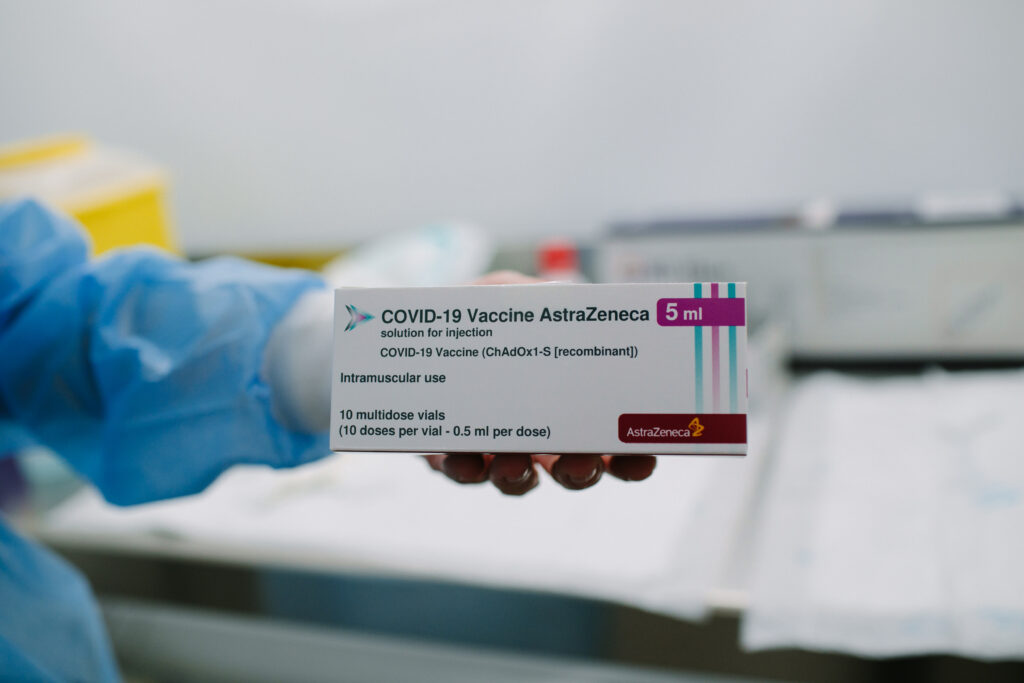

Moreover, COVAX has encountered difficulties with its distribution efforts in the Global South. The facility has laid out plans to purchase and distribute 350 million doses of the Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine. This particular vaccine is being sold at a lower price — under $4 per dose compared to the Pfizer vaccine, which costs approximately $20 — and is thus most suitable for efforts to vaccinate lower-income populations en masse. The AstraZeneca vaccine is also much easier to transport and deliver to poorer communities. Whereas many vaccines, such as the Pfizer and Moderna jabs, require extremely cold storage during transportation, this vaccine can be stored at a normal refrigerator temperature. This allows for distribution that is more affordable and accessible throughout the Global South. Despite its positive attributes, the AstraZeneca vaccine is proving to be significantly less effective against a new South African variant of the virus that accounts for over 90 per cent of the country’s cases and is quickly spreading across the world. The South African government has even halted its rollout of the AstraZeneca vaccine due to its ineffectiveness. However, COVAX has signalled that it intends on continuing to deliver these doses to low and middle-income countries as it races to vaccinate as many people as possible, even if the vaccine proves less effective.

Finally, the COVAX facility has also encountered funding troubles that arise from its total reliance on donations from wealthier countries and organizations. As recently as December 2020, leaked documents from Gavi stated that “the risk of a failure to establish a successful COVAX facility is very high,” and that the program urgently needed an additional $4.9 billion USD in funding. Shortly after President Joe Biden took office in January 2021, the United States joined COVAX, providing a boost to the program. However, COVAX leaders have stated that the facility needs further funding, and that “in the end, the most wealthy countries need to step up and fill that gap.” It is self-evident that COVAX is providing an invaluable service to lower and middle-income countries that are also being ravaged by the pandemic but do not have the ability to purchase their own vaccines.

Nevertheless, the success of COVAX lies at the mercy of a number of unpredictable factors, ranging from the rise of vaccine nationalism to the apparition of new variants to a lack of funding. As the world begins to emerge from the COVID-19 pandemic, the struggles of COVAX provide insight into the challenges of equitable vaccine distribution and pandemic relief. Although higher-income countries may soon achieve herd immunity and return to normalcy domestically, the pandemic will only truly end when everyone has access to the vaccine, regardless of the wealth of their country. COVID-19 has created uncountable challenges for international relations and health equity, but this could very well be the most consequential one yet.

Featured image: “COVAX: Vaccine Equity” by Adam Steiner

Edited by Jacob Lokash