Cruel, Unusual, and Costly: The Death Penalty’s Got To Go

Both moralists and pragmatists should agree–the Biden administration should finally end judicial execution in America.

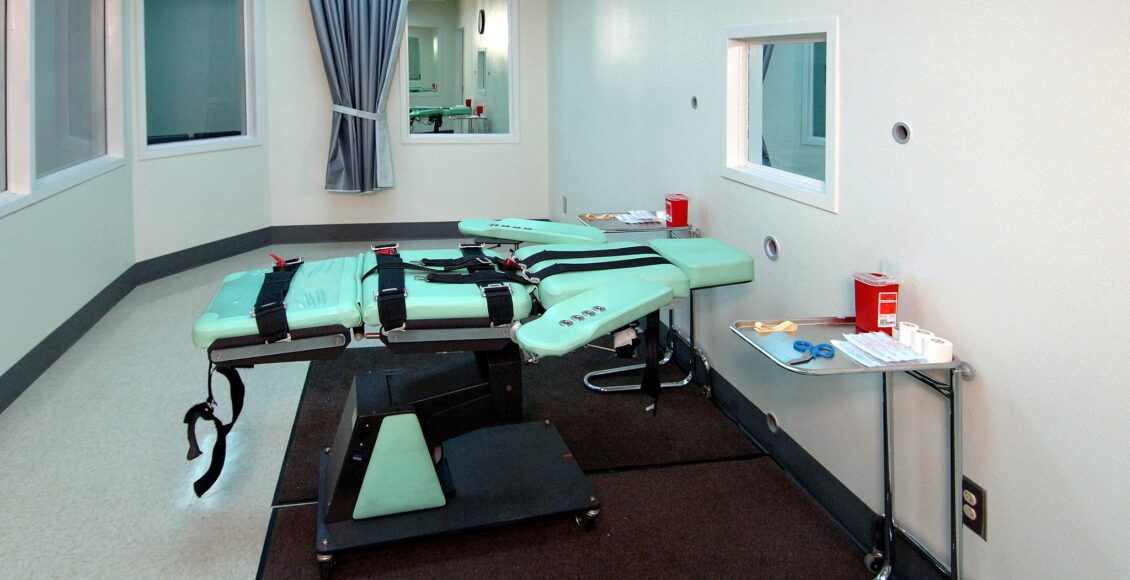

"File:SQ Lethal Injection Room.jpg" from the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation) is in the public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

"File:SQ Lethal Injection Room.jpg" from the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation) is in the public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Just last month, Virginia became the latest American state to abolish capital punishment. This is a historic step, given that Virginia, which has carried out the most executions in American history, is now the very first Southern state to abandon the practice. With Virginia, 23 states have now banned the death penalty, and 11 others haven’t executed anybody in at least ten years. Until July 2020, the federal government hadn’t executed anybody in 17 years. In the mid-1990s, when support for the death penalty was at a record high of 80 per cent, some years saw more than 300 Americans sentenced to death; since 2015, however, that number hasn’t topped 50.

It’s not just the frequency of executions that has declined — it’s also public approval of capital punishment. With just over half of Americans in favour, its approval is currently the lowest since 1966. Surveys conducted in the past three years reveal that a record-high 60 per cent of Americans favour life in prison over capital punishment, while only 54 per cent consider the death penalty “morally acceptable,” and just 49 per cent believe it is fairly applied.

With record-low approval rates and decreasing state application, why does the US remain the only liberal democracy to continue judicial executions?

In fact, a 1972 Supreme Court ruling did discontinue capital punishment, condemning it as unconstitutional. But it was reinstated just four years later after states nominally revised their sentencing laws — updates that failed to address the unfair and unequal application that initially provoked the suspension. Despite its declining use, many states continue to allow or even actively employ the death penalty, and there was a recent spike in its federal application. Former President Donald Trump, who had voiced strong support of capital punishment when he campaigned, authorized 13 federal executions in the last 6 months of his presidency.

The death penalty has withstood shifting international human rights norms and evolving public opinions at the domestic level and remains a fixture of the American judicial system. This suggests that, while Biden’s anti-death penalty stance could help temporarily halt the use of capital punishment, he’s sure to encounter resistance if he seeks to abolish it outright. However, whether moral or practical, the reasons to end capital punishment are numerous and compelling. America needs to finally join its international cohort in abolishing judicial execution definitively.

Cruel, unusual, and unreliable: moral problems

In 2015, a majority of those supporting the death penalty cited the belief that it was morally justified in cases of murder, despite also readily acknowledging the risk of wrongful convictions and executions. Advocating for the killing of one person in response to the death of another seems like a logical fault, especially considering the very real risk of wrongful convictions. In fact, 185 people have been exonerated while on death row in the past half-century, and there are numerous cases where “strong evidence of innocence” has emerged only after the convicted party was executed. It is neither right nor prudent to carry out these irreversible decisions, particularly when the system making them is so flawed.

What’s more, the system is deeply biased, primarily along racial lines. People of colour make up a disproportionate percentage of total executions since 1976, and represent a majority of inmates currently on death row. Black Americans in particular are most likely to receive death sentences, and the most likely to have them carried out. But the racial imbalances don’t end there. Despite the fact that only about 50 per cent of murder victims are white, 75 per cent of cases resulting in a death sentence have white victims. Given this clear and substantial bias in favour of whites in the application of the death penalty, it is perhaps unsurprising that there are also racial differences in its support. As of 2015, the support-opposition ratio of the death penalty among Black Americans was almost the exact inverse of that among white Americans: 63 per cent of white respondents were in support of judicial executions, while 57 per cent of Black people were opposed. More than 75 per cent of Black respondents said white offenders were less likely to receive a death sentence, but only about half of all survey participants said racialized minorities were unfairly disadvantaged in the application of the death penalty, with white respondents far less likely to acknowledge systemic racial bias.

Finally, with capital punishment comes pain which means it might constitute cruel and unusual punishment, which is unconstitutional. In recent decades, almost all US executions have been conducted via lethal injection, which is meant to be quick and painless. However, there have been dozens of botched executions by lethal injection, leading to prolonged and painful deaths. Even when carried out correctly, lethal injection is widely and increasingly considered inhumane. Concerns were raised in 2008 about the likelihood that prisoners executed this way experience significant pain that they are unable to communicate to their executioners, given the particular combination of drugs used. Recent research supports this, suggesting that death by lethal injection tends to be far from the quick, painless death many imagine. Instead, evidence from inmate autopsies suggests that dying this way is akin to asphyxiation or drowning, which would make lethal injection agonizing and terrifying, rather than offering a relatively peaceful death.

Ineffective and expensive: pragmatic concerns

Capital punishment in the United States is ineffective in reducing crime and incredibly expensive. There is long-standing and widespread consensus in the scientific community that the death penalty is an ineffective deterrent for violent crime. A significant number of ordinary people share this belief — including about half of those who supported the death penalty in the 2015 survey referenced earlier. This undercuts the pro-death penalty argument that judicial executions make society a safer place by making an example of violent offenders.

Further, capital punishment is much more expensive than life without the possibility of parole — an expense borne by taxpayers. There are an abundance of extra costs, mostly legal ones, in death penalty cases. Because of the gravity of what’s at stake, death penalty trials are much more complex and can last over four times as long as those where the prosecution recommends life in prison. Capital cases take longer to go to trial and are complicated by the need for more careful jury selection, a thorough gathering of evidence, and consultation with various experts, all of which is costly. Because of socioeconomic disparities in the justice system, most death penalty defendants cannot afford their own lawyers, and must be represented by state-appointed counsel, so the state pays for both the defence and the prosecution. Most cases where prosecutors seek the death penalty don’t actually result in a death sentence, so the high costs of capital trials often represent a waste of taxpayer dollars: extra money is invested in a more complex and prolonged trial that ultimately produces the same result as vastly cheaper trials which seek a life sentence in the first place. Where criminals do receive a death sentence, there are extra appeals following the initial trial, further elevating costs. At this stage, the majority of death sentences are overturned. And even when sentences are upheld, few are ever actually carried out; most death row prisoners end up serving a life sentence, albeit under costlier death row incarceration. Ultimately, this means that in the vast majority of cases, the taxpayer costs are up to 1.5 times higher in death penalty cases, while the end result is the same as if a life sentence had been sought and imposed from the very beginning.

If the flawed moral justification, uncertainty in conviction, and failure to deter crime were not convincing enough, capital punishment’s high financial costs are the final nail in its proverbial coffin. If death sentences are ultimately nothing more than a waste of tax dollars, even the staunchest supporters of the practice should have serious doubts. It is also important to ask ourselves whether any system that punishes crimes and offers redress to victims with such flagrant inequality can truly be considered “justice.” I think the answer is clear.

The death penalty has got to go, and the moment is ripe for the Biden administration to take this much-needed step. The abolition of capital punishment is long overdue. But now, as America struggles to deal with the economic ravages of the COVID-19 pandemic and to address the long and painful legacies of racism and persistent societal discrimination, putting an end to this deeply problematic system might represent one small step towards healing.

Feature Image: “File:SQ Lethal Injection Room.jpg” from The California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation is in the public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Edited by Selene Coiffard-D’Amico