Debt, Masks, and Tech: Why COVID-19 Won’t Mean the End for China’s Belt and Road Initiative

The Belt and Road Initiative promotes the "Chinese Dream" of a China revived of its ancient glory. "Great Wall of China" by matt512 is licensed under CC BY 2.0

The Belt and Road Initiative promotes the "Chinese Dream" of a China revived of its ancient glory. "Great Wall of China" by matt512 is licensed under CC BY 2.0

The developed economies of North America and Europe have shown no immunity to COVID-19’s devastating impacts. In April, the International Monetary Fund forecasted a dire three per cent contraction for 2020, marking the global economy’s steepest downturn since the Great Depression. China, an economic superpower only continuing in its rise, has been no exception to this trend. Within the first quarter of 2020, China recorded its first contraction in decades: a 6.8 per cent loss in gross domestic product. The weakening of China’s economy has led to disruptions to the country’s manufacturing and supply chain activities, consequently applying downward pressures onto other economies in the region. In this regard, COVID-19’s economic toll carries substantial implications for President Xi’s geopolitical interests, especially China’s most ambitious economic blueprint, The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). However, China is proving that it will not allow COVID-19 to bring its economy to a standstill. With Xi’s playbook for Chinese-style globalization, the BRI will be able to continue serving Beijing’s political and economic aspirations abroad.

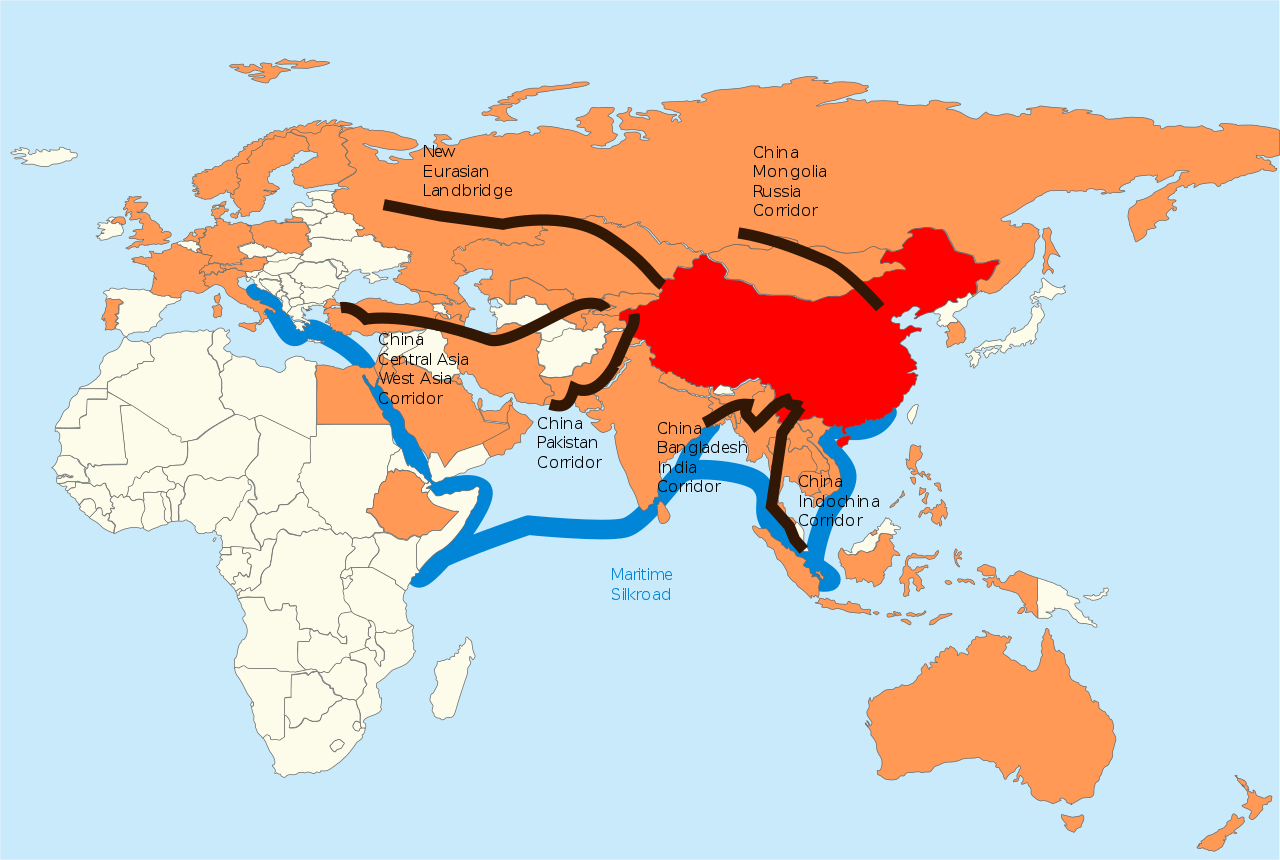

Proposed in September of 2013, the BRI addresses the critical infrastructure gap that constrains trade, investment, competitiveness, and connectivity in developing and developed countries alike. While Xi boasts about the multilateral character of the BRI by claiming “friendship” and “neighbourliness,” the initiative works primarily to China’s benefit. The BRI promotes Xi’s “Chinese Dream” agenda by acting as a channel for sharp power — a novel approach that emphasizes manipulation and pressure — and soft power. In doing so, the BRI creates asymmetric foreign dependencies between China and vulnerable nations in the developing world.

The predatory undertones of China’s development initiatives have amplified growing animosity from rivals like the United States. Fortunately for competitors, COVID-19’s economic toll on China’s domestic economy has extended to Chinese overseas projects and investments, compromising the supply chains that sustain BRI projects. The freeze on the flow of Chinese labour caused by travel restrictions aimed at containing the virus’s spread has caused progress to be suspended and slowed in partner countries like Cambodia, Indonesia, and Pakistan. Additionally, Beijing faces a tarnished reputation as a result of its attempts to conceal the outbreak when it was discovered in Wuhan back in December of 2019. Since concealment, it has also suffered from a damaging rhetorical war with the U.S. Luckily for Beijing, the BRI’s infrastructure projects represent only the physical component of Xi’s greater Belt and Road agenda.

Over the past two decades, China has become the world’s largest official creditor, lending especially to developing countries. While its role is well understood, the extent of its influence remains obscure due to lack of transparency and data. As a result of the deep financial strain brought on by poor health infrastructure and high pre-emergency debt levels during the COVID-19 crisis, many low-income countries have turned to multilateral financial institutions for emergency lending. On April 15, all members of the G-20 agreed to extend a debt moratorium to their poorest borrowers. Though China signed the G-20’s pledge, it is excluding hundreds of large “preferential” BRI loans extended through its banks, effectively forcing poorer nations to choose between servicing their BRI-related debt and importing essential goods and medical supplies.

Fears of debt-trap diplomacy have shrouded the BRI since its inception, and to this end, China’s partial debt moratorium will force developing nations to “choose China”. However, since 2013, nearly half of China’s new loans have been to nations considered to be at high risk of default; if Beijing continues without issuing debt relief, the seizure of assets over the inevitable wave of defaults will hurt China’s creditor status. Thus, in mitigating these risks amid growing calls for relief, China will likely need to engage in debt restructuring. With many developing countries owing as much as 30-40 per cent of their debt to the economic superpower, BRI debt renegotiations will act as a tool for China to curry the political favours necessary to fuel Xi’s “China dream.”

After a phone call with Italian Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte in mid-March, Xi pledged to deliver medical assistance and indicated China’s willingness to work with Italy in the development of the Health Silk Road. The Health Silk Road (HSR) is no novel feat; it has been written into the BRI agenda since at least 2017 under the auspices of enhanced health connectivity parallel to the BRI’s land and maritime networks. The COVID-19 crisis has merely acted as an accelerator for the HSR. China’s push for global health leadership has been loud and clear; the country has exported equipment and medical assistance on a bilateral basis to no fewer than 89 nations. Beijing’s mask diplomacy has targeted the likes of Ukraine, Uganda, the Philippines, and Indonesia, where a 40-tonne shipment of medical equipment, personal protective equipment, and test kits was received in April. Concerns that the HSR will supplant the World Health Organization (WHO) have also emerged. With the retreat of the U.S., as well as other major powers from multilateral institutions, the WHO has failed to play to expectations, allowing China to continue leveraging its soft power. Though the HSR exists mostly as an extension of the BRI into the global health sector, the combined effort at public relations and language that emphasizes a “community of common destiny for mankind” will allow China to use the HSR to not only redeem its international reputation, but reaffirm its aptness for global governance.

While the HSR represents the first non-physical prong at the forefront of Beijing’s expansionist plans, the Digital Silk Road (DSR) represents the technological ambitions that comprise the second. Introduced in 2015, the DSR aims to fill the gaps in digital infrastructure across the Belt and Road through the expansion of China-centric digital and telecoms infrastructure projects. Though having been seemingly jeopardized at the onset of the pandemic, China has recuperated to the point where COVID-19 has created new opportunities for the country’s technological ambitions to flourish.

The persistence of 5G expansion aside, the DSR has been critical amid the pandemic due to its intimate linkage with the Health Silk Road. With the spread of the pandemic, governments have been compelled to hone in on the use of health surveillance technology. Such technology is prevalent in countries like Singapore and South Korea — which, to an extent, have inspired the usage of digital tools to track user data and control infections, demonstrating a high degree of success. While China’s affinity for mass surveillance is no secret, the outbreak of the virus has given a pretence for the actions of the Chinese government. Facial recognition technologies, smartphone apps, and colour-based health codes have been rolled out over the last few months to monitor public health and contagion risk. Should China opt to export its public health solutions to the vulnerable, technologically deficient states along the DSR, it will not only add an additional prong to its health diplomacy strategy, but bolster its digital rise.

From the beginning of the outbreak until now, the soft power upon which Xi’s “Chinese Dream” relies has certainly taken a hit. As such, the impacts of COVID-19 extend well beyond domestic affairs and hold significant implications for Beijing’s foreign policy. The Chinese government now relies on alternative — albeit predatory — channels to redeem its legitimacy amongst those who depend on China the most. And while the situation appears bleak for developing countries, it is important to look beyond realist calculations and acknowledge the optimistic perspective. Through the BRI and its sister initiatives, China offers developing countries opportunities to strengthen their economies in the long-run, build up their health infrastructure — which COVID-19 has proved to be especially essential — as well as the opportunity for technological development that will have a lasting impact on societies.

However, realism must take precedence. The very fact that the BRI has been written into the constitution of the Communist Party of China underscores not only the primacy of the project, but the degree to which China’s rise has been institutionalized. Accordingly, Xi’s plans for Chinese-style globalization will continue serving Beijing’s overseas ambitions, even at the expense of the economically weak. In understanding the way that China has both maneuvered the global health crisis and capitalized on countries with weak economies, overstretched healthcare systems, and technological deficiencies, it is safe to say that for Beijing, COVID-19 will merely be a set-back.

Featured image: “Great Wall of China” by Matt Barber is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Edited by Nina Russell