The Deep and Dark Web of International Politics

(image by Ruben Molina, via Flickr)

(image by Ruben Molina, via Flickr)

The Internet is an ubiquitous entity. It dominates the lives and practices of many. The birth of the World Wide Web in 1989 marked an unprecedented expansion of information and communication, with a remarkable risk – reward ratio. Since the advent of the Internet, it has been impossible to prevent the effects of vastly expanded, quickly available information from seeping into the political sphere. Nowadays, diplomacy is conducted through emails and online political forums. State decisions are made upon heaps of intelligence, usually circulating around the Web. Digital trade has increased fourfold. The Internet has thus proven strong enough to change the dynamics of international politics. However, it has also been a double edged sword. With a rudimentary understanding of the Deep and Dark Web, it is easy to see how cybercrime can go unchallenged and even unnoticed. Thus, the Internet is increasingly becoming a tool to gain leverage over large international institutions and states through government hacking and inter-state espionage. Such virtual activity has profound implications on the future of politics.

Digital Hidden Figures

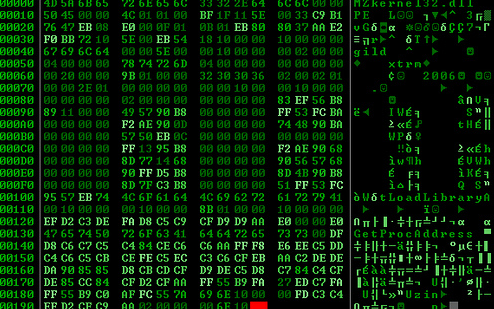

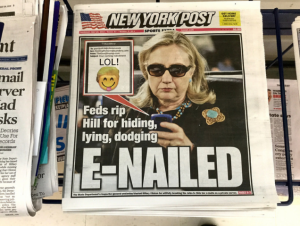

The Deep Web has also been called the invisible web: data stored on the Deep Web does not appear on conventional search engine queries. For instance, an individual’s gmail account is considered to be part of the Deep Web as it cannot be accessed through a Google search. The Deep Web is believed to hold approximately 95% of all the data in the world. A popular analogy given to describe the visible part of the Web is the tip of the larger iceberg. Hillary Clinton’s email leaks involved interaction with the Deep Web. According to certain media sources, most notably PJ media, much ‘hacking’ was not required to obtain Clinton documents because there is a relatively low level of security in the Deep Web.

The Dark Web, on the other hand, is the portion of the Internet that is intentionally hidden from public viewership. It can only be accessed through certain browsers. For instance, The Onion Router (Tor) is a software that directs Internet traffic or communications through several layers of encryption so that it becomes near impossible to trace content back to the IP address of the user. Dark Web or Darknet sites comprise of about 1% of all data. Initially, the US government helped fund the creation of Tor for circumstances that demand anonymity. For example, journalists that are concerned about their safety in authoritarian regimes have an interest in keeping their work hidden from their government. The concept of the Dark Web can thus be traced back to concerns for privacy. Nevertheless, the nature of the Dark Web easily lends itself to malign purposes. Drug and gun sales, child pornography, human trafficking, and hitman hires are some of the activities that are conducted within the Dark Web realm. Retrieving data from these parts of the Web has implications for international relations and law. Firstly, illicit trade deals could be monitored and regulated, strengthening international law enforcement and human rights protections. Secondly, governments that recruit computer specialists to digitally spy on other governments might influence state decisions and infringe on rights of sovereignty.

U.S – Russian Digital Relations

To put these concepts into context, there has been much attention devoted recently to Russian hacks againt Washington, which have leaked sensitive US government information to the international masses. In June, a hacker or a group of hackers by the name of Guccifer 2.0 leaked documents from the Democratic National Convention (DNC). These documents included the Democratic campaign plan against then GOP candidate Trump and a series of emails and statements that put Hillary Clinton in an unfavourable light. On the 6th of January 2017, the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and the National Security Agency (NSA) released a report recognizing that Russia’s cyber activity, espionage, and other propaganda efforts aimed to undermine confidence in the 2016 presidential elections. The report also claimed that such invasive cyber operations could only have been sponsored by senior officials within the Russian government. Although other evidence suggests a smaller Russian role in these cyber attacks, the fact remains that hacking has become a reality that governments with sensitive information must be wary of. It is unsurprising that these hackers were operating through the Deep and Dark webs, since anonymity was required. Tracing the leaks back to the culprit is is a tedious and lengthy process that sometimes comes to no avail. For instance, there remain real doubts as to the nationality of Guccifer 2.0. The lack of evidence on the origins of hackers makes it difficult for the case to be presented in a court of law, further complicating the position of states.

A Hacktivist’s Ethical Code and IR

Much like the French Revolution’s trifecta slogan, Anthropologist Gabriella Coleman from New York University posits that Privacy, Freedom, and Access make up the ethical code of the typical computer hacktivist. Because such ideals are inextricably linked to the international political sphere, she argues, a Liberal value system undergirds hacking activity. Realist or Institutionalist paradigms of International Relations do little to explain hacktivist motivations.

One of the thematic focuses of International Relations is the causes for conflict between states. Rational Choice Theorists see the asymmetry of information as the major cause of international conflict. In a research report entitled Digital Diplomacy, author Nicholas Westcott argued that the Internet serves as a levelling ground for states, because states no longer have to be materially wealthy to gain intelligence like lobbyists, diplomats or personnel for covert operations. Although funding for education and computer science programs is required to buff up intelligence departments, basic access to Internet translates into access to massive amounts of information. Moreover, the kind of government information that lies within the realms of the Deep and Dark Webs is probably better suited for helping states make informed decisions. By the same token, however, states might be subjecting themselves to the intake of information that may be interpreted as alarming. The idea here is that the more information one state receives about other states, the greater the chance of wrongly ascribing offensive motivations. Within the neorealist perspective, the logical conclusion of misinterpretation tends to be a conflict spiral or security dilemma, wherein states begin to preemptively prepare for potential war.

The question of sovereignty is also a major theme within International Relations. The digital age is characterized by cross-border interaction within the space of seconds. Hacking inherently transcends borders, and the elusive nature of hacking brings up issues for sovereignty. Without effective cyber regulatory measures, a state becomes vulnerable to intrusions and theft of both public and private property. This unlawful appropriation of property reduces the state’s claim on legitimate authority. Furthermore, a state having discrediting intelligence on another government may allow the former to exert forms of indirect control resembling neocolonialism. Although such outcomes are undesirable, the leverage game in world politics is known all too well.

Finally, civil societies’ and private sectors’ access to information about their governments through the Deep and Dark Webs has implications for those governments’ legitimacy. Firstly, the government becomes more accountable to the people. Edward Snowden’s leaks of NSA documents revealed government infringements of the Fourth Amendment justified by security needs. The government protests that followed are a good illustration of how an informed civil society can act as a formidable check on state power. Secondly, activity on the Dark Web is hard to regulate. The scope for private entities to engage in illegal arms buying, for example, can be quite wide. This is especially problematic for countries of the global South, where the monopoly over violence may not lie with the state, but other fringe groups with easy access to weapons. Both scenarios undermine legitimate governments.

Cyber Law and Order

A vast amount of crime on the visible net is unaccounted for as it is. Illegal activity on the Deep and Dark Webs frequently goes unnoticed. Due to the elusive nature of the Dark Web, the number of transactions is difficult to ascertain. However, people studying cryptomarkets estimated that between 2013 and 2015, about 360,000 sales of drugs were made amounting to approximately $50 million across known Darknet sites like Agora, Evolution and Silk Road 2. With the addition of other types of markets like arms dealing and human trafficking, the profits generated within the Dark Web are quite large. Identifying the participants in these transactions is also difficult because the networks they work within change sites almost every week or every day. Thus, cyber law has a long way to go in terms of being developed like its intellectual property counterpart. There have been measures to boost cyberlaw. For example, the International Conference on Cyber law, Cyber crime and Cyber security, which took place in India in 2014, discussed issues affecting homeland security and drafted steps for overcoming these problems for the states around the world. These measures have been steadily implemented over the years.

Conclusion

The digital and virtual advancements of the 21st century have shaped international relations and politics. However, the risk – reward ratio is beginning to tip unfavourably as we get an improved understanding of the Deep and Dark Webs. Cyber law in its current form is ill-equipped to deal with the rate and frequency at which digital crimes are committed. The debate about the morality of hacktivist endeavours rages on, but it is important to recognise their increasingly critical role in international politics. The Internet at large must also be seen through a nuanced perspective given people’s security and privacy concerns.