Defunding the Police: The Power of Resource Reallocation

On May 25, 2020, a white police officer from Minneapolis knelt on George Floyd’s neck for almost nine minutes, killing him. His murder has caused outrage in the US and across the world, placing the issue of police brutality at the centre of our collective focus. Underpinned by patterns of systemic racism, police violence against Black, Indigenous and People of Colour (BIPOC) is rampant and has sparked debate about the role of law enforcement within communities, leading many to question the relevance of a police force altogether.

In a matter of days, “Defund the Police” became the battle cry of countless protesters in the US and beyond. While the idea is portrayed as radical by some, it has rapidly slipped into mainstream discourse and is now seen as a potential solution to a seemingly unsolvable issue. Defunding can mean anything from light budget cuts to completely abolishing police departments, which would fundamentally reshape the way societies operate. The rationale behind the idea is straightforward: police departments are overfunded, and officers are ill-equipped to respond adequately to most situations they face on a daily basis.

From a resource allocation perspective, redirecting funds typically reserved for policing expenses could have many welfare-enhancing impacts. In Canada, for the 2017-2018 period, total policing expenditures exceeded $15 billion. Although this includes policing expenses at the municipal and provincial levels, as well as the Royal Canadian Mounted Police’s (RCMP) budget, the number is quite high relative to other government allotments. In Ontario and Quebec, the country’s most populated provinces, these expenses respectively amounted to $5.5 billion and $2.7 billion over the same period. Reallocated elsewhere, part of these funds could support the development of programs directly tackling the very issues that warrant police presence.

The main argument against defunding police services is the need for a law enforcement agency capable of dealing with crime. While crime remains a pressing issue in numerous cities, a focus on intervention capacity and punishment rather than prevention shows a deep misunderstanding of what triggers it. Indeed, empirical evidence demonstrates that crime arises when the basic socioeconomic conditions for well-being are not being met. This reality implies that investing in social services, including affordable housing initiatives, accessible education programs and mental health services is crucial to crime reduction. Yet, social services and crime prevention programs remain chronically underfunded. To address this, the Quebec government announced an additional investment of $23 million in social services between 2017 and 2018. However, this number pales in comparison to the $2.7 billion spent on the province’s police expenditures during the same period. The amount allocated by the Ministry of Public Safety to crime prevention initiatives is also telling: between 2018 and 2019, only $50 million were spent on key programs. Comparing these figures clearly shows that resources are inequitably allocated.

Often, police officers intervene in situations where other, better-trained professionals such as social workers and mental health experts could respond more effectively. These officers, who are frequently dispatched for tasks related to social services, lack training in victim counselling and communication with vulnerable groups, such as children and individuals with mental health issues. This can have disastrous outcomes, specifically for BIPOC. In May, Regis Korchinski-Paquet, an Indigenous-Black woman fell to her death in Toronto after police were called to check up on her following a family dispute and an epileptic seizure. A month later, Chantel Moore, an Indigenous woman, was shot and killed in her home in Edmundston while officers were performing a wellness check. In both cases, the involvement of professional mobile crisis teams rather than police officers likely would have saved lives. Tragedies like these show that, to achieve better outcomes, the decision to defund police departments must go hand in hand with a commitment to better fund community-based safety programs. There is, in fact, concrete evidence that such strategies are highly effective. The city of Eugene, Oregon, has been dispatching teams of crisis workers and medics to respond to non-violent situations for 31 years. The program, Crisis Assistance Helping Out on the Streets (CAHOOTS), received upwards of 24,000 calls in 2019 and asked for police backup in only 150 instances. Evidently, this system provides a better-suited alternative to police officers in most cases.

Over-reliance on police services to address other types of non-violent situations is also a cause for concern. In addition to wellness checks, these situations include trivial matters such as traffic stops or noise complaints. Between 2017 and 2018, police services across Canada received 12.8 million calls for service. These calls, which are related to non-violent events pertaining to public safety or well-being, are estimated to make up 50 to 80 per cent of those received by police departments across Canada. Combined with the fact that police training overemphasizes the use of force and only brushes over deescalation techniques, this creates conditions ripe for unjustified brutality. In April 2017, Demetrius Bryan Hollis, a 21-year-old Black man was kicked in the head by white police officers during a traffic stop. That same week, a Sacramento police officer threw Nania Cain, a Black man, to the ground after stopping him for jaywalking. Dealing with minor offenses should not involve the use of weapons or aggressive tactics, and, by extension, does not warrant police intervention. Instead, well-trained and unarmed community members could play an important role in solving such situations without violence at all.

Spending reallocation offers tangible grounds for defunding police departments, but when done superficially it glosses over an unacceptable truth. Recent events, both in Canada and the US, have clearly shown that in addition to often being inadequate, policing as we know it is laced with systemic racism. Over funding police departments directly contributes to patterns of racialized police brutality by providing departments with enough resources to support overpolicing. Since policing disproportionately affects BIPOC, specifically those who live in lower income areas targeted by police, they are often on the receiving end of brutality. In Toronto, Black residents are 20 times more likely to be fatally shot by police than white residents. Further east, in Montreal, Black and Indigenous individuals are four to five times more likely to be stopped by police than their white neighbours. Across the country, Indigenous citizens are routinely brutalized and beaten by RCMP officers. In recent years, efforts have been made within police forces to tackle systemic racism, mainly through implicit-bias training for officers. Nevertheless, guidelines for these courses are vague, and there is no evidence that they are actually effective. If anything, the current situation shows that reforms stemming from inside the system are unsuccessful, and this reality should be reason enough to justify defunding police departments.

When an institution is so blatantly biased against certain groups of society, small-scale reforms fail to bring about the change needed to ensure that all residents are safe. Fully remodelling the current system by divesting away from police departments and investing into better-adapted, truly non-discriminatory frameworks of community-led safety is the way forward. In the past weeks, cities from Vancouver to New York City have submitted proposals to reduce their police forces’ budgets. In Los Angeles, the city council has introduced the idea of a non-violent crisis response team, which would remove responsibility from the LAPD. Earlier in June, the city of Denver initiated its Support Team Assistance Response (STAR) program, an initiative through which social workers and health professionals are dispatched for non-violent crisis situations. Perhaps most strikingly, the city of Minneapolis has vowed to fully dismantle its police department, pledging to rethink public safety from the ground up. “Defund the police” is no longer just a slogan, but a concrete policy proposal, grounded in undeniable evidence that the system is fundamentally inadequate. Our willingness to change it is, for many, a matter of life and death.

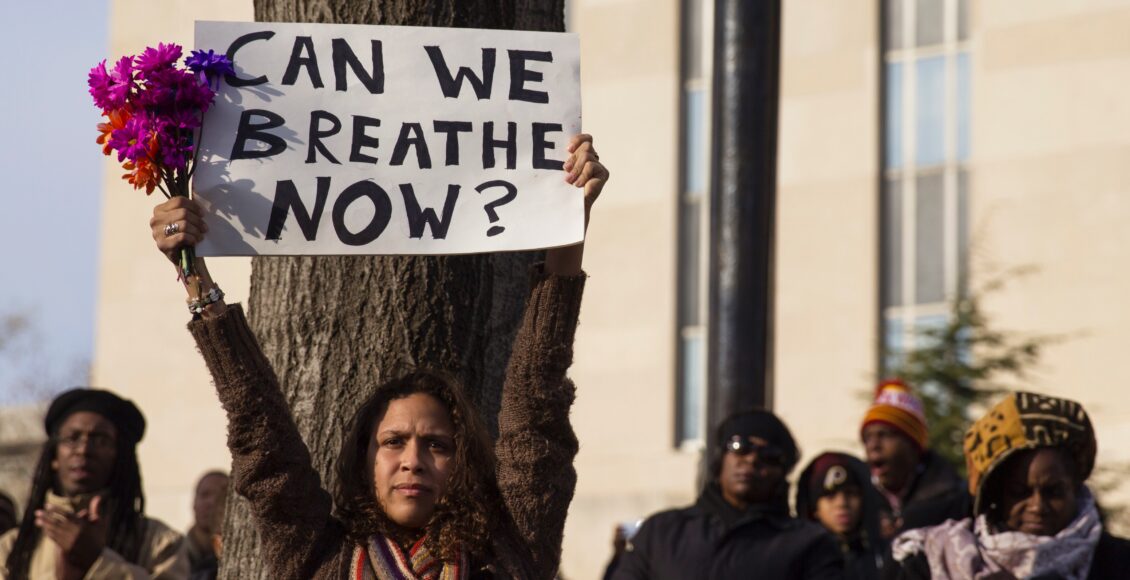

Featured image: Protesters at the Justice For All March on Washington, DC in 2014. “Can We Breathe Now? Black Lives Matter” by Lorie Shaull, licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

Edited by Elizabeth Hurley