Don’t Cry for Argentina

We are but in the early days of 2016. Looking back, the sheer madness of the past year is astounding. Understandably, the power changes, corruption charges, economic crises, border disputes, and mysterious deaths that took place are nothing new to observers of Latin American politics. Yet while these echoes of the past cannot be forgotten, we must also emphasize the fresh starts that occurred in many countries.

Some are half comedic, half tragic: in the perennially troubled Guatemala, the president — forced to resign on corruption charges, along with the vice-president and several cabinet members — was replaced with a former comedian.[i] Other changes, though fraught at the time with political uncertainty, seem inevitable in retrospect. The end of Chavism in Venezuela was one such move, while another occurred in Argentina late last year, when the country took a step back from Kirchnerism.

Kirchnerism, the modern incarnation of Argentina’s Peronist past, is characterized by the same husband-and-wife-style leadership and populist bent. It began when Néstor Kirchner was elected in 2003, hot on the heels of the economic crisis of 2001, which saw Argentina default on billions in debt. Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, his wife, took office in 2007; she served two four-year terms, the second ending in December of last year. The pair was known for pro-poor protectionist policies aimed at both growth and development, and are often praised for lifting the Argentine economy out of its 2001 slump.

Since the death of her husband in 2010, Kirchner has earned herself a reputation for her bullish and passionate rhetoric, at times overshadowing the policies themselves.[ii] Like many Latin American leaders, past and present, she is loved and reviled in equal measure. With issues such as that of the Falkland Islands (known to the Argentines as las Islas Malvinas), some critics argue that this rhetoric served to distract the population from the poorer economic performance of the past few years.[iii] Many of these strong stances have mired her government in controversy, whether through her blistering condemnation of “vulture” funds responsible for Argentina’s 2014 debt default, her reactionary call to reform the secret service following the mysterious death of prosecutor Alberto Nisman in January of last year, or her ongoing, high-profile clashes with news magnates in the midst of new legislation.[iv] Meanwhile, she garnered praise from some groups due to her legalization of gay marriage and her expansion of poverty-reduction programs.[v]

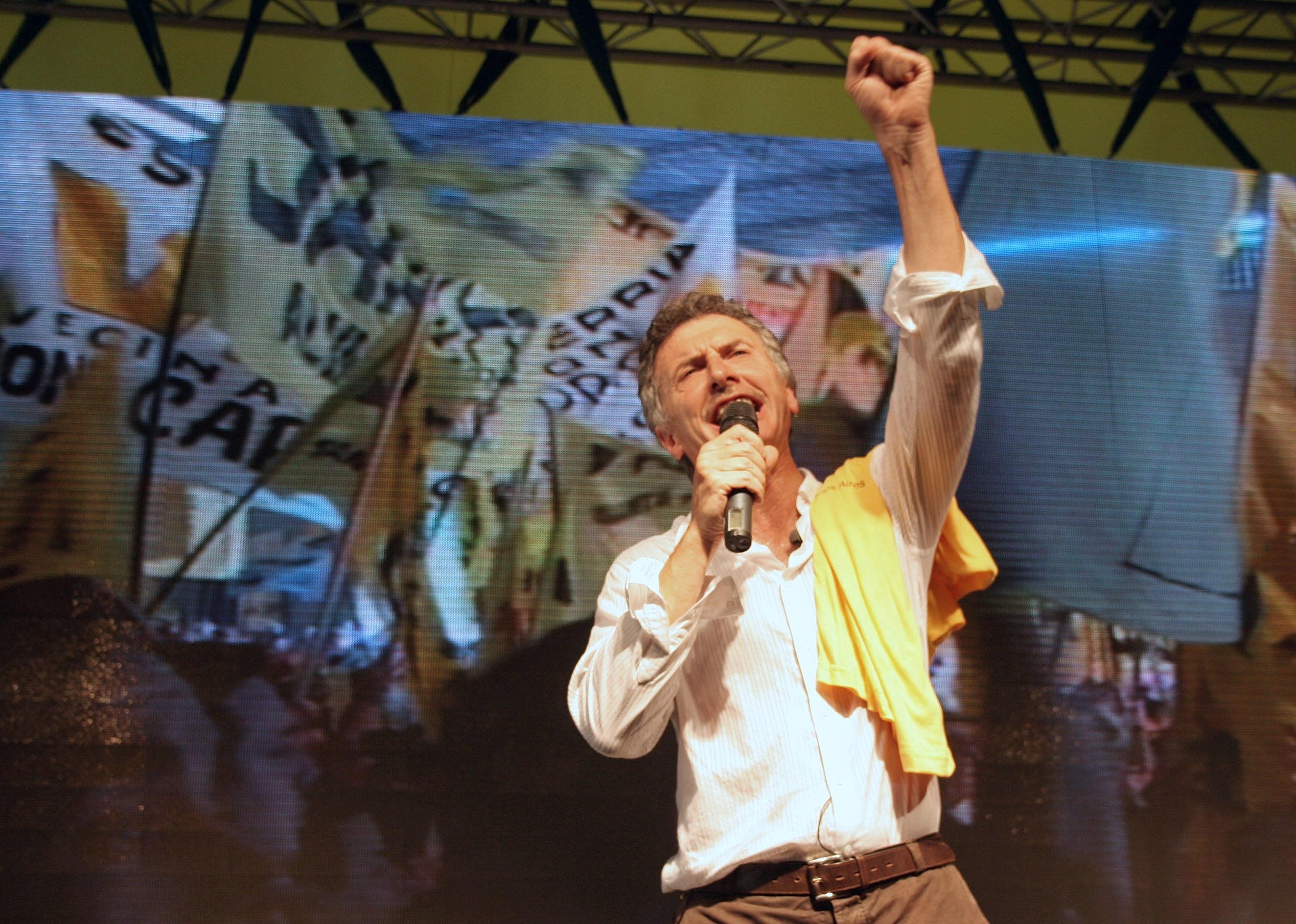

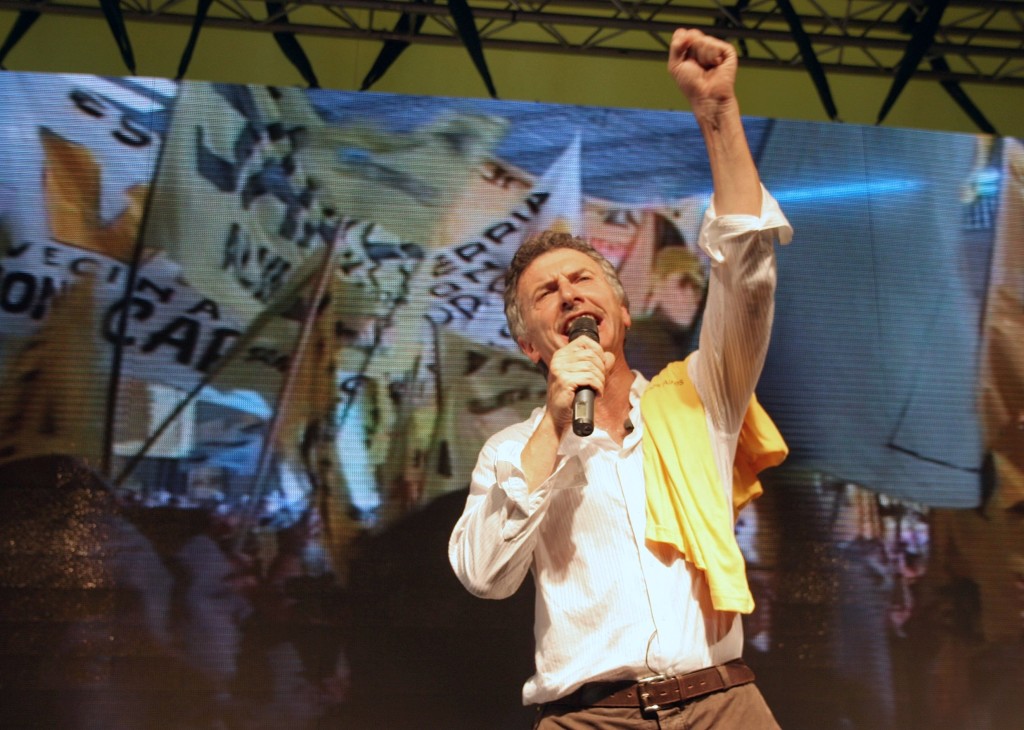

At the end of an eventful twelve years, however, the Kirchner era is over. On November 22, after an initial presidential vote had failed to produce a clear winner, a runoff between the two main candidates resulted in the upset victory of Mauricio Macri, former mayor of Buenos Aires.[vi] Although he and rival Daniel Scioli’s platforms were not vastly different, their allegiances were.[vii] While Scioli was publicly loyal to Kirchner and the ruling party, having served as Néstor’s vice-president, the wealthy Macri formed his own Propuesta Republicana (PRO), a more conservative political party.

In some ways, the changes needed to reboot the Argentine economy – including Macri’s recent currency devaluation – would have been easier to accomplish under a president like Scioli, who would have had a broader support base in government.[viii] However, the results bode well for democracy in the country. As many have pointed out, this is the first time in almost a century that a non-radical, non-Peronist has taken office democratically.[ix] No longer will the upper middle class see its interests represented by an intrusive military.[x] Since Kirchner’s faction still retains a majority in both houses of the legislature, the opposition will also have a strong democratic foundation.

Of course, political compromise and cooperation would best serve Argentina’s interests, but they seem to be in short supply. Long disputes between Kirchner and Macri about the latter’s inauguration ceremony resulted in a noticeable lack of attendance on Kirchner’s part when the day finally came on December 10.[xi] Similarly, while Macri was originally slated to bring Scioli on his impending visit to the World Economic Forum in Davos, a recent statement has named Frente Renovador leader Sergio Massa to go instead.[xii]

At the end of any long political tenure, there is a palpable itch for change. With slowing economic growth, and increasing political controversy, the transition from Kirchnerism is understandable. Yet the Kirchners were popular for a reason. Their populist protectionism allowed for growth with development, an aim cherished among the disadvantaged in a region where neoliberal economic policies wrought such devastation. Their rhetoric allowed Argentines to feel like more than just pawns of the global political machine. Their supporters will not back down without a fight.

In my opinion, Argentina is on the verge of a political system that is the best of both worlds. Despite the tensions between the two factions, both presidential candidates made clear that some economic restructuring would need to occur. This way, the left becomes a watchdog to ensure that this restructuring occurs without the economic chaos followed by the neoliberalism of the 1990s. As one of the largest and strongest Latin American countries, Argentina needs this rational push-and-pull to achieve both growth and development. Scioli and Macri seem moderate enough to let this happen. The real obstacle to success is Kirchner.

With some sectors already benefitting under Macri, Kirchner and Scioli – and the opposition in general – must do what they can to ensure that the new economic measures are gradual and fair. Since Macri has already raised import prices by devaluing the peso, any subsequent policies must be introduced slowly to placate urban workers. While he promises to be honest and fair, it is in the best interests of the opposition to hold him to account without vilifying him. While this does not seem like a stretch for Scioli, it may well be for Kirchner, who rushed in new measures and ambassadors right before ceding power to Macri.

Kirchner has served the country fairly well; the coming days will show whether she can continue to do so as part of a productive opposition, or whether her rhetoric remains as divisive as ever.

[i] Americas Society Council of the Americas. 2015. “Year in Review: Latin America in 2015 and What’s Ahead in 2016,” December 12–15. http://www.as-coa.org/articles/year-review-latin-america-2015-and-whats-ahead-2016.

[ii] Gilbert, Jonathan. 2015. “Her Time Is Up, but Argentina’s President Is Not Going Quietly.” The New York Times, December 7–15, sec. Americas. http://www.nytimes.com/2015/12/07/world/americas/her-time-is-up-but-argentinas-president-is-not-going-quietly.html?_r=0.

[iii] Lloyd-Roberts, Sue. 2015. “How Argentines Feel About the Falkland Islands Dispute.” BBC News, March 6–15. http://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-21673504.

[iv] CBC News. 2015. “Argentina Debt Crisis: Talks Collapse, Staggering Economy Slips into Default,” July 31–15. http://www.cbc.ca/news/world/argentina-debt-crisis-talks-collapse-staggering-economy-slips-into-default-1.2723440;

The Associated Press. 2015. “Alberto Nisman, Argentinian Prosecutor Shot in Apartment, Sought President’s Arrest.” CBC News, February 3–15. http://www.cbc.ca/news/world/alberto-nisman-argentinian-prosecutor-shot-in-apartment-sought-president-s-arrest-1.2944119;

Van Woerden, Simon. 2012. “Media Law Reform Pits Argentine Executive Branch Against Judiciary.” Americas Quarterly, December 7–12. http://www.americasquarterly.org/content/media-law-reform-pits-argentine-executive-branch-against-judiciary.

[v] Prengaman, Peter. 2015. “Argentina Presidential Election: Mauricio Macri Brings Conservatives to Power.” CBC News, November 22–15. http://www.cbc.ca/news/world/macri-election-argentina-1.3330518.

[vi] “The World Factbook: Argentina.” n.d. The Central Intelligence Agency. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/ar.html.

[vii] Caparros, Martin. 2015. “¿Con Cristina Vivíamos Mejor?” El Pais, November 21–15, sec. Analisis. http://internacional.elpais.com/internacional/2015/11/21/actualidad/1448124565_060967.html.

[viii] Ibid.

[ix] Ibid.

[x] Schamis, Hector E. 2015. “Una Nueva República En Argentina.” El Pais, November 23–15, sec. Columna. http://internacional.elpais.com/internacional/2015/11/23/mexico/1448238090_560504.html

[xi] Associated Press. 2015. “Argentina: New President Macri Promises Major Changes And Honesty.” NBC News, December 10–15. http://www.nbcnews.com/news/latino/argentina-new-president-macri-promises-major-changes-honesty-n477966.

[xii] Clarin. 2016. “Finalmente, Macri Viaja Con Massa Y No Con Scioli Al Foro de Davos,” January 5–16, sec. Politica. http://www.clarin.com/politica/Finalmente-Macri-Massa-Scioli-Davos_0_1498650272.html.