Engaging Taipei: The Taiwan Travel Act

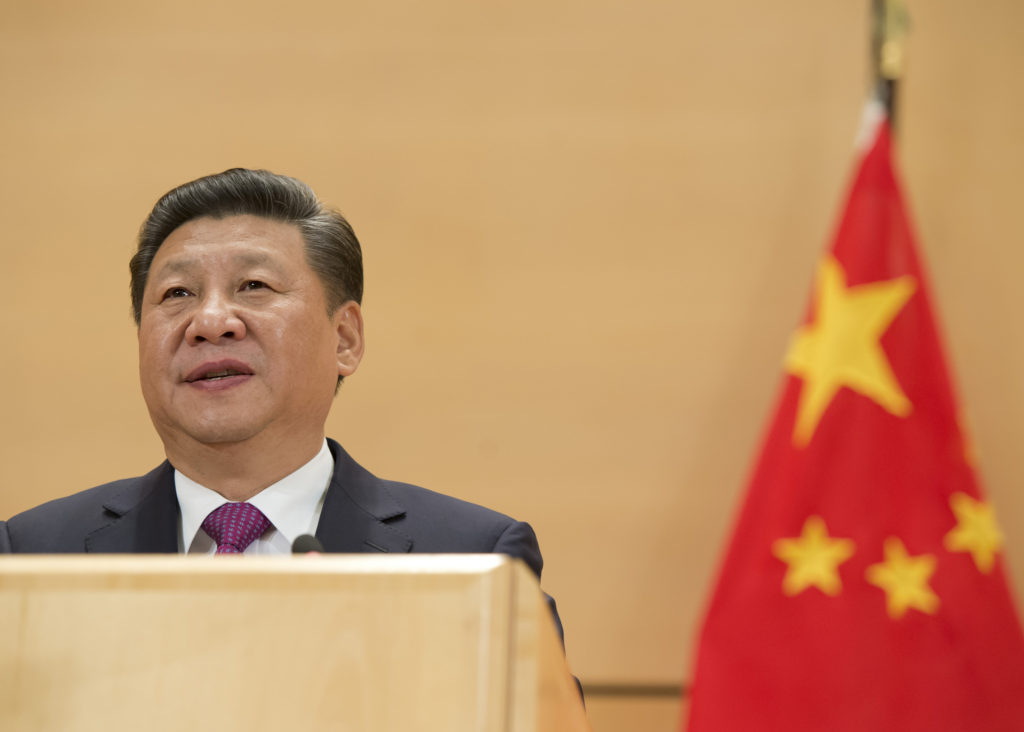

On March 16, 2018, U.S. President Donald Trump signed the Taiwan Travel Act. The bill supports high-level visits between officials of the United States and Taiwan, and also aims to encourage Taiwanese economic and cultural representative offices to conduct business in the United States. This seemingly innocuous bill was met with quick and extreme criticism from the Chinese government, with President Xi Jinping declaring, “Any actions and tricks to split China are doomed to failure and will meet with the people’s condemnation and the punishment of history.”

The relationship between the United States, Taiwan, and China has often been marked by offensive responses to outward inoffensive actions. At the heart of these relations lies the legacy of the One China Policy – or the 1992 Consensus – as well as the greater historical framework that contextualizes the issue that plagues Taiwan’s existence: its paradoxical identity as a renegade province as well as a de-facto independent state.

The Chinese Civil War, fought for a staggering 22 years between 1927 to 1949, saw the ideological split between the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and the Chinese Nationalist Party (the Kuomintang, or KMT) manifest into a deadly military conflict. The conflict intensified during the Communist Revolution of 1949 – concluding in a large-scale defeat for the KMT. The remnants of the defeated KMT government fled to the island of Taiwan with 600,000 nationalist troops and 2 million sympathizers. There, it declared that it, as the Republic of China (ROC), remained the sole rightful authority of all of China, with Taipei its capital. On the other side of the Taiwan Strait, the victorious CCP established Beijing as the capital of the People’s Republic of China (PRC), a communist state with 23 provinces – the 23rd being Taiwan.

.jpg)

At the time of the split, the international community largely chose to accept the ROC’s claim due to heightened Western disdain of communist ideology in the Cold War era. Indeed, the United States and the Soviet Union were key secondary players during the Civil War, with the USSR funding CCP troops and the US backing the KMT. In the aftermath of the split, more states recognized the ROC as a legitimate state than the PRC. However, the normalization of relations between the United States and the PRC in the 1970s and 1980s through the Three Joint Communiqués marked the beginning of Taiwanese international isolation. The first communiqué – issued during Richard Nixon’s seminal visit to China in 1972 – acknowledged American commitment to the One China Policy, a “consensus” that states both Taipei and Beijing agree that only one sovereign state exists which encompasses both mainland China and Taiwan, but disagree which side of the strait holds this lawful authority.

Relations between the United States and Taiwan are currently governed by the Taiwan Relations Act, passed by Congress in April 1979. The bill permits the United States “to provide Taiwan with arms of a defensive character“, and “to maintain the capacity of the United States to resist any resort to force or other forms of coercion that would jeopardize the security, or the social or economic system, of the people on Taiwan.” The intentional ambiguity of the act has led both Beijing and Taipei to conclude that the United States is ready, if not precisely bound, to intervene militarily if China were to ever attempt a forced takeover of Taiwan. However, the Taiwan Relations Act passed, alongside a number of unwritten self-imposed regulations that reaffirmed Washington’s commitment to the One China Policy. These limitations included the prohibition of five top officials of Taiwan – president, vice president, prime minister, foreign minister, and defense minister – from visiting Washington.

Thus, for over thirty years, Washington has balanced an obligation to the One China Policy with a military commitment to defend Taiwanese sovereignty. Beijing and Taipei have both come to accept this American ambiguity, with Beijing testing the limits of American defense guarantees in showcases of military brinksmanship such as the Taiwan Strait Crises of the late 1990s; which resulted in the largest display of American military prowess in East Asia since the Vietnam War as a means to defend Taiwan from hostile missile tests conducted by the Chinese People’s Liberation Army.

However, the election of President Donald Trump and the resulting policy incoherence that has marked his administration has increased doubt in the role that the US aims to play in cross-strait relations. President Trump first publicly questioned whether the US needed to observe the One China Policy in December 2016, after breaking from tradition and speaking with Taiwanese President Tsai Ing-wen directly on the phone. He then switched track in February 2017 with a phone call with President Xi Jinping that reiterated American commitment of the One China Policy. Nonetheless, Beijing’s infuriation of Trump’s approval of the Taiwan Travel Act jeopardizes the claim of American support of the status quo. While Tsai welcomed the legislation as a sign of Washington “supporting Taiwan’s democracy”, Beijing views this as the administration acknowledging Taiwan as more than just a province of China, and thus, a break in the One China Policy.

Indeed, there is a growing sentiment amongst prominent politicians, policymakers and observers that the US approach to the China-Taiwan conflict has backfired. The American expectation that Washington would be able to “shape China’s trajectory” and bring forth political openness was what was responsible for the US policies implemented on Taiwan in the 1970s. Over forty years later, it is clear that Beijing is not trending towards democratic transition – in fact, Xi Jinping’s recent abolishment of presidential term limits signals to the extreme contrary.

While Taiwan underwent a successful democratic transition in the late 1980s and early 1990s, the West remained committed to engage China in order to benefit from its economic rise and widened market access. This engagement continues to this day, as China utilizes its economic clout to isolate Taiwan – with states steadily ceasing formal diplomatic relations with Taipei in order to benefit from the Chinese market. As of 2018, only 19 out of 193 UN member states recognize Taiwan – these are just a handful of islands or small, developing states largely scattered in Oceania, the Carribean and Central America. This has perpetuated Taiwanese isolation, effectively cutting Taipei’s communication with the rest of the world. Certainly, the Taiwan Travel Act itself aims to rectify a “lack of communication” that has caused US-Taiwan relations to suffer due to self-imposed restrictions on high-level visits.

If the United States continues to pride itself in being a promoter of global democracy, it must aim to re-engage Taiwan with the international community. Certainly, the success of the Taiwanese democratic transition ought to serve as an excellent model for states in the Asia Pacific. Therefore, bills such as the Taiwan Travel Act are steps in a seemingly correct direction for the promotion of democracy and peaceful global engagement in East Asia.

Editor: Shivang Mahajan