Failing to Protect Our Protectors: The US Military’s Sexual Violence Problem

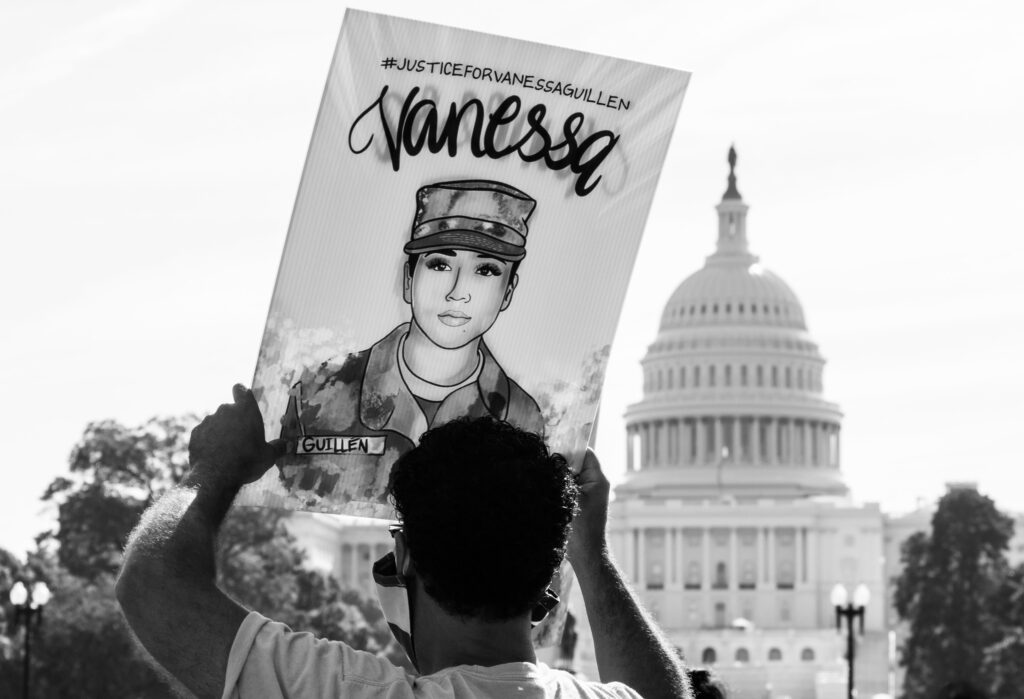

“Ma’am, I am more afraid of my own soldiers than I am of the enemy.” Those are the words of a woman who has served as a nurse for the US military in Afghanistan and Iraq. Intra-military sexual assault — sexual assault that occurs between fellow service members — is estimated to impact over 14,900 service members annually. The statistics around intra-military sexual assault paint an ugly picture. In 2016, one-in-four women and one-in-three men were assaulted by someone in their chain of command. A third of intra-military sexual misconduct victims were discharged within seven months of reporting the abuse they suffered, and of the limited number of sexual assault cases that the military actually took action on, a meagre 4 per cent of offenders were convicted of a sex offence.

Despite increased discourse around workplace sexual assault in recent years, the US military avoids addressing its sexual assault problem time and time again. The complete lack of transparency in military courts has coalesced around a toxic and misogynistic work culture and a history of “don’t ask, don’t tell,” entrenching this problem within the ranks of the world’s most powerful military. While reforming the US military court system has become a bipartisan issue in recent years, it has failed to gain enough traction for major structural change. With its commitment to bipartisanship, the Biden administration has the opportunity to push for long-overdue reform of an outdated institution.

At the root of it all is a complex, bureaucratic-military legal process divorced from justice. When reporting sexual violence in the military, survivors are faced with a series of undesirable options with unforeseeable consequences. For instance, the first decision they must make is who to make a report to — survivors must choose between law enforcement and healthcare personnel, sexual assault response coordinators, and victim advocates within the military. This decision shapes the course of action available to the victim, most notably by determining the report type. Restricted reports, in which the victim’s privacy is ensured, are available exclusively to victims who report to military personnel rather than law enforcement. However, if a victim files an unrestricted report, no investigation is initiated and the case is filed so that there is no “personally identifying information” of the perpetrator.

Alternatively, if a victim chooses to alert law enforcement, they are pushed through a lengthy process, wherein they must relay their accounts of the assault to numerous people, including their commanding officers and peers. To be given a trial, the Military Criminal Investigation Organization must first deem that there is sufficient evidence, then the superior commander must determine if the evidence substantiates a sexual assault claim. Of approximately 7,000 annual cases of reported sexual assault, only 16 per cent are approved by commanders to be of sufficient evidence, and only 11 per cent go to trial. For the trial, the victim must decide between a judge or jury, composed of their direct superior and fellow service members respectively. The jury is selected by a high-ranking officer — in the United States Air Force, for example, the 12th Air Force Commander will select jurors based on their age, education, and length of service. This has clearly problematic implications for jurors to acquit perpetrators, who are fellow service members.

As there are a number of obvious barriers to achieving justice through military courts, survivors have occasionally pursued action in civilian courts instead. The issue with this alternative is that, as stated in the Feres Doctrine, all varieties of intra-military harm — including sexual violence — are insulated from judicial review. As a result, notable cases that have gone to the civilian courts, such as Cioca v. Rumsfeld and Klay v. Panetta, have been unsuccessful. Because of the practically absolute immunity from judicial review outlined in the Feres Doctrine for intra-military harm, there are no incentives for defence officials to change the culture around such crimes.

It is relevant to note that the nature of sexual assault in the military comes with a lengthy history of sexual violence as a weapon of war. The horrific implication of this history is that it remains part of the basis for why military courts were given jurisdiction to rule on issues that occur during duty; the fundamental argument for military court separation is that the military creates a unique set of circumstances that civilian jurors cannot understand or evaluate. For instance, fellow service members can evaluate the goals of a soldier’s mission when an offence was committed, and the confidentiality maintained by a separate military court process can be important to national or even international security.

Neither of these considerations is relevant in cases of intra-military sexual assault. Not only is there no basis for considering the unique circumstances of the military in these cases, but sexual violence also does not occur for the betterment of any mission. Furthermore, the expertise of service members or commanders in evaluating the circumstances of a mission does not apply in the case of sexual assault. Given the military’s historic failure to properly deal with sexual violence and other gender and sex-based crimes, it can be argued that military officers are uniquely unfit to judge.

As for possible solutions, scholars of intra-military sexual assault have debated over whether to shift jurisdiction and responsibilities to international or domestic avenues. Proponents of outsourcing intra-military sexual assault cases claim that a shift has already occurred, making it acceptable in the eyes of many to deal with such crimes through international human rights bodies. They argue that shifts in treaty law have broadened the jurisdiction of bodies such as the International Criminal Court (ICC), allowing some cases of intra-military sexual assault to be processed under the ICC’s supervision. This solution is not ideal because it attempts to outsource a survivor’s legal rights to an international body, which essentially documents their domestic government’s failure to hold the perpetrator accountable. This is also an extremely inaccessible option, both in terms of the time and financial means required to pursue this route. Furthermore, domestic governments with developed militaries are likely to reject such a solution, perceiving it as a major breach of state sovereignty and national security.

The most realistic and pragmatic approach is to add an exception to the Feres Doctrine, removing sexual violence as an offence protected from civil liability. This would allow for survivors of intra-military sexual violence to pursue legal action that is more comparable, or even identical, to what civilian survivors face. While this is an imperfect system, at the very least, positive change created through the momentum of the Me Too movement and other factors pushing for reforms in the handling of sexual assault cases can apply equally for service members.

In recent decades, reforming military courts has seen support from conservatives and progressives alike. In 2013, Senator Kristen Gillibrand forwarded a comprehensive bill that would have decreased the influence of military commanders in sexual assault cases, garnering notable support from Republican Senators Ted Cruz and Rand Paul. Even the late conservative Justice Antonin Scalia urged Congress to modify the Feres Doctrine in 1987. The Biden administration has a unique opportunity to act on its commitment to bipartisanship in this instance. While the appointment of General Lloyd Austin came with a commitment to combatting the issue of intra-military sexual assault, a promising signal for change, it will ultimately be up to Congress to overcome partisan bickering, and unite in protecting those who so honourably protect them.

Featured image: “Gen. Lloyd Austin” by United States Forces Iraq, licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Edited by Matthias Hoenisch