For Queen or Country

The role of the Governor General is being called into question, so is Canadian republicanism a solution?

Julie Payette’s resignation as Canada’s Governor General this winter over allegations of workplace harassment has made Canada’s de facto head of state newsworthy again, albeit for all the wrong reasons. The monarchy is usually taken for granted in Canadian politics and culture, but recent events at Rideau Hall have revived debate regarding whether the role of the Governor General is really a durable, or even desirable, institution in modern society. Given the many pundits and politicians publicly calling for abolishing the position in light of Payette’s resignation, there is a critical need to examine the merits of the monarchy in Canada and whether republicanism is a better way for Canadians to govern themselves.

Imperialism, Christianity, and anglocentrism — Oh my!

The Governor General is appointed by the Queen on the advice of the Prime Minister, and acts both as the stand-in for the Crown and as a ceremonial figurehead of Canadian identity. They perform important civic functions such as summoning Parliament and giving royal assent to Parliamentary bills. Despite the position’s importance to the Canadian political system, relatively little spotlight is placed on the Governor General since they are considered to be an apolitical ornament to our democratic system, and thereby “above” the political fray. At face value, the Crown’s source of authority is absurd to our modern sensibilities. The fact that a single individual in a castle halfway around the world has been directly anointed by the Christian God to bestow legitimacy on the executive, legislative, and judicial functions of our government is rather fantastical. Having an unelected head of state, with enormous wealth and fortune, wrestles uncomfortably with our notions of democracy and egalitarianism. The constitutional union of the Anglican Church and the state seems untenable in an increasingly secular and multicultural Canadian society. For many Québécois, having the Queen as the head of state is a reminder of conquest and subjugation by the British Crown. Similarly, sharing a monarchy with the United Kingdom is an ever-present reminder of Canada’s colonial past and present with respect to its relationship to Indigenous peoples.

In 1999, Australia held an unsuccessful referendum to abolish the role of Governor General and become a presidential republic instead. Though modern Canadian politics has no such formal republican movement, Canadians are not exactly ardent royalists. In a recent Ipsos poll, 53 per cent of Canadians were skeptical of the monarchy’s future after Queen Elizabeth II passes away. Monarchism varies regionally, with Quebec most supportive of severing ties, while British Columbia, Alberta, and Ontario are the least receptive to change. Across the pond, seven in ten Britons support the continuation of the monarchy — though interestingly, a slight plurality of Britons would prefer Prince William, not his father Prince Charles, to succeed as king. Notably, Queen Elizabeth II herself remains remarkably popular, enjoying an 81 per cent approval rating among Canadians. However, public opinion polling indicates this affection for the Queen is likely due to her personal brand rather than a reverence for the monarchy as an institution. Even if republicanism lies on the fringes of Canadian political discourse, there could be a serious appetite for constitutional change in the not-so-distant future.

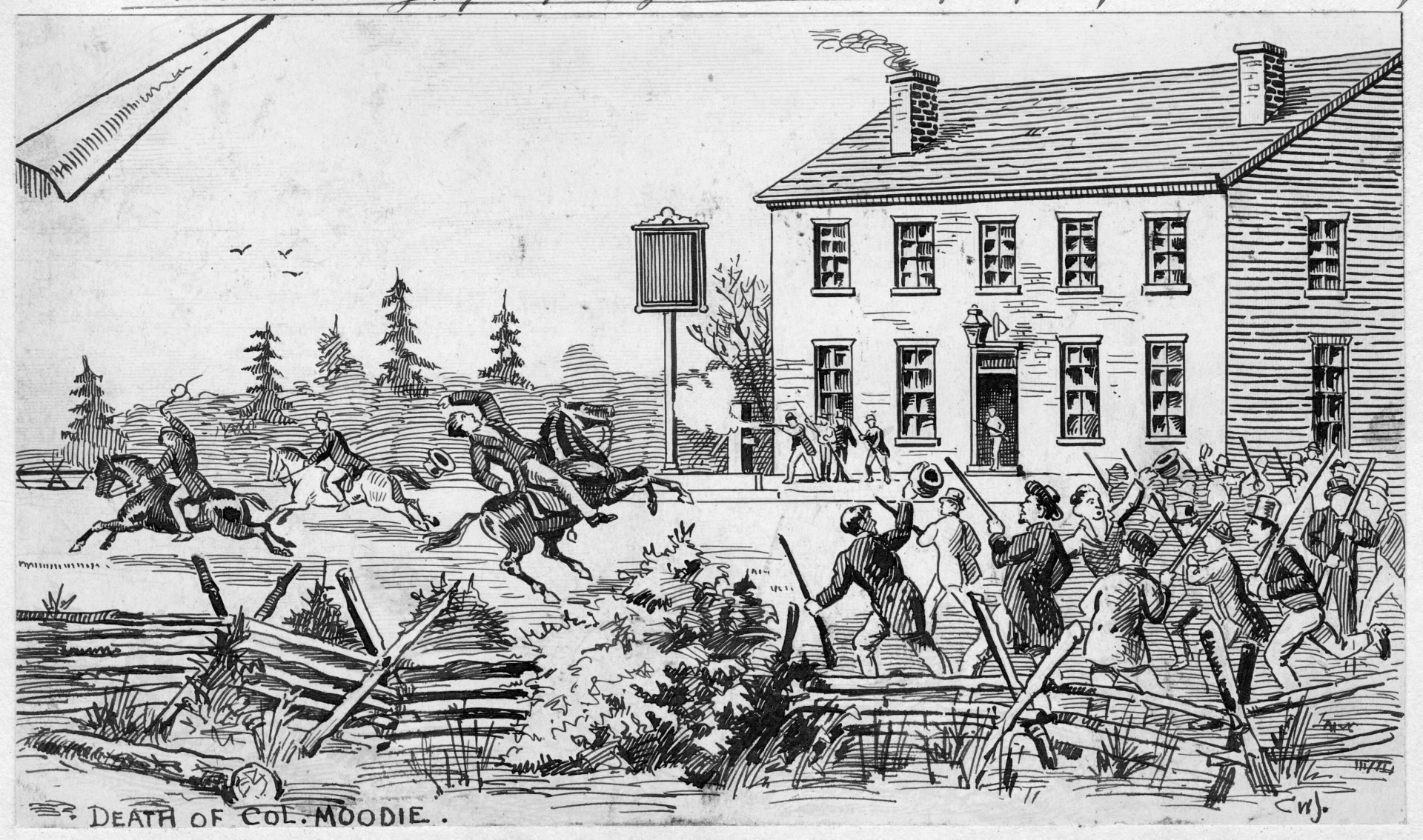

“Shooting of Col. Robert Moodie in front of John Montgomery’s tavern, Yonge St., west side, near Montgomery Ave.” by Toronto Public Library Special Collections is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

Send her victorious, happy and glorious

These concerns about the monarchy notwithstanding, the position of Governor General, and indeed the entire Westminster system, is a remarkably convenient fiction. The Crown provides an institution that, in theory, places the loyalties of the Canadian government in something greater than the politics of the day. The Queen, through the Governor General, acts as an umpire to Canada’s constitutional system, ensuring the Prime Minister holds the confidence of the House and that each government does not overstay its mandate. Unlike the American presidential system, Canada’s executive and legislative powers are combined, giving the cabinet the power and authority to take decisive action quickly while the President and Congress often endure drawn-out negotiations. Indeed, the quick implementation of the Federal Government’s Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB) versus the slow, highly politicized process to legislate America’s pandemic stimulus cheques is a timely comparison of the two systems of government.

The monarchy is also deeply embedded in Canadian society. The command structure of the Royal Canadian Armed Forces would have to be rethought, as the Governor General is the official Commander-in-Chief of the army. Numerous Canadian institutions bear the royal brand, namely the Royal Canadian Mint, Royal Canadian Mounted Police, and, of course, the Royal Institute for the Advancement of Learning. Changing our head of state is perhaps theoretically desirable, but republican sympathizers should not underestimate the tedium and complexity of disentangling the royal family from Canada.

The political and societal convenience of keeping the Westminster system is not the only reason to continue the monarchy in Canada. Indigenous peoples signed their treaties with the Crown as their partner, often before the Confederation of Canada, and the Queen and her representatives remain the keepers of protocols for non-Indigenous Canada. In the Royal Proclamation of 1763, King George III recognized that Indigenous peoples had rights to the lands they occupied, and promised to protect them. The Crown is responsible for the historic obligations it made under successive treaties, so ending Canada’s colonial legacy is far more complicated than simply abolishing the Crown.

The Canadian Republic

Abolishing the monarchy, and by extension the position of Governor General, is no easy feat. Canada’s constitution requires the approval of Parliament, the Senate, and unanimous approval of all the provincial legislatures in order to amend the provisions concerning the Queen and Governor General. Even if the republican cause reached this high standard, it would likely be deeply fractured over which system should replace our constitutional monarchy.

A system modelled off of Germany could have a ceremonial head of state elected by parliamentarians, which would closely resemble the constitutional status quo in Canada — perhaps being too similar to justify the complicated legal battle. Meanwhile, Canadians’ increasingly unfavourable opinions towards the United States mean a similar Presidential system with clear separation of powers would be unlikely to take off as a replacement. Given that not-being-American constitutes much of Canadian identity, a movement towards a Presidential style of government would also likely rile up Canada’s many civic nationalists. Furthermore, having an elected head of state would be a dramatic change to Canadian political culture, and could usher in an unwelcome era of heightened partisanship.

Though it is hard to imagine why, tabula rasa, Canadians in the twenty-first century would choose to be governed by a constitutional monarchy, the forces of history and path dependence have made it today’s political reality. Aside from the balkanization of Canada or the collapse of the monarchy in Britain, it is exceptionally unlikely that a republican movement will offer a meaningful alternative to the Governor General and the Westminster system. It would require quite a revolution for the sun to set on the Canadian monarchy. Nevertheless, the Crown and those in whom its power is invested should not rest on the laurels of maintaining the status quo. Treaty obligations towards Indigenous peoples remain neglected, and trust in Canada’s public institutions continues to decline. Though the monarchy of the future should continue to defend our laws, it will probably not give us cause to sing God Save the Queen.

Feature Image: “Signing of the constitution / Signature de la Constitution” by BiblioArchives / LibraryArchives is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Edited by Nina Russell