How Brexit Could Break the Irish Border and the Entire United Kingdom

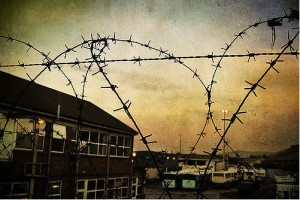

Physical separation between Northern Irish Catholics and Protestants.

Physical separation between Northern Irish Catholics and Protestants.

On the 23rd of June, nearly 52% of the United Kingdom decided to vote in favour of leaving the European Union. There is a tendency thus far for individuals to limit their analysis of Brexit to London, or even England more generally; however, other regions within the UK are set to experience Brexit uniquely, as the socio-economic repercussions for will differ subsequently. Despite the avoidance by political elites and an England-centric media on the topic of Northern Ireland throughout and after the campaign, recent history must be considered to address the urgency of the potential consequences to the Irish border. Despite media and political emphasis on England’s battle with Brexit, the implications for Northern Ireland present a higher level emergency to the stability and livelihood of the United Kingdom.

To understand the root of the instability of the Irish border, we must go back to the 1920s, when the entirety of Ireland gained independence from the United Kingdom, with the option to remain being afforded to Northern Ireland, which it accepted due to the protestant majority. The Catholic minority, which formed armed movements such as the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF), the Ulster Defence Association (UDA) and most notably, the Irish Republican Army (IRA) as a means to unite with its Catholic Southern neighbour, was opposed to the consequences of the transfer of power from the Nation of Ireland to the United Kingdom. These movements engaged in a long and bloody conflict against the British Army, which was only resolved with the signing of The Good Friday Agreement (GFA) on April 10th, 1998.

Britain leaving the EU consequentially entails leaving the EU trade zone as well. Brexit negotiators need to keep in mind that the border between the Irish Republic and Northern Ireland will be the only land border that the UK shares with an EU member. Brexit involuntarily added enormous value to a border that is historically known for being ambivalent. The Republic of Ireland and Great Britain both joined the European Economic Community in 1973. Brexit has implications on borders, tariffs, power sharing, as the majority of laws and rules on both sides of the border have been derived from the European Union. It is no wonder, therefore, that more than 55% of Northern Ireland voted to remain in the European Union. The UK will need to reintroduce tariffs on the goods it imports, and will face the imposition of tariffs on its own goods from EU member states, but what will happen to the Irish border? Will goods flow freely? If not, could this lead to the re-emergence of Northern Irish Unionists? The signing of the GFA, which brought relative peace in Northern Ireland, relied largely on the fact that the United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland were both member states of the European Union. Britain’s exit from the EU could compromise the agreements of 1998. Tensions between unionists and anti-unionists in Northern Ireland are not new and could be severely heightened in these trade negotiations.

For the past decade, the border has been porous. The extent to which Brexit will influence border dynamics and the political impact is currently unknown. If negotiations go as intended by Theresa May, showcased through her speech, “Brexit means Brexit”, the border may begin to parallel that between France and Switzerland, with relatively fluid passing but nevertheless strict border controls. Will the Catholics in Ulster accept peacefully British-made laws and restrictions on their ability to cross freely to the South? The process of signing the GFA was no small achievement. Both sides want to avoid the resurgence of the violence that was experienced from the 1960s up until the end of the 1990s. Negotiators simply cannot overlook Irish history as a key component of these negotiations if they wish to maintain peace, as Brexit could become a potential tool to revive anti-unionist sentiments. The current situation warrants a higher sense of urgency on the part of negotiators in determining the new role of the Irish border as a prominent trade zone between the UK and the EU.

In opposition to the rest of Great Britain, more than 60% of Scottish voters voted to remain in the European Union. Being a generally pro-EU region, the outcome of the referendum is setting the tone for the renewal of a new referendum regarding Scottish Independence. Having missed independence by a margin of 55% to 45% in 2014, Scottish independence supporters are hopeful that Brexit will lend legitimacy to their call for independence again so that they can join the EU. The potential for Scottish independence opens the conversation for anti-unionism, as if both Northern Ireland and Scotland became independent, the United Kingdom would drastically shrink in size.

However, if Scotland were to become independent, it would be unsure of its membership in the EU, whereas Northern Ireland could become a part of the Republic and ensure its own membership. Northern Ireland is therefore a more realistic candidate for independence, though it’s unclear if the Protestant Republic would be open to an Irish union.

The Brexit referendum is the expression of the British people in an effort to recover their sovereignty from the European Union, but it opens the door for the constituent parts of the United Kingdom to recover their own sovereignty. The potential for Irish reunification is not ancient history, and the strong tensions that were only legally mended with the Good Friday Agreement should not be forgotten. The tensions between Protestants and Catholics can still be seen with the existence of peace lines.

Brexit negotiations should give the Irish border question special attention, as if handled incorrectly, Brexit could make a complete hash of the Irish border. The negotiations that lie ahead will not be simple, and will no doubt go down in history as either contributing to the current peace settlements between Northern Ireland and Britain, or to the downfall of the Good Friday Agreement and the dismantling of the modern United Kingdom by setting a precedent for independence.