How Do We Get Canada’s Youth to Vote?

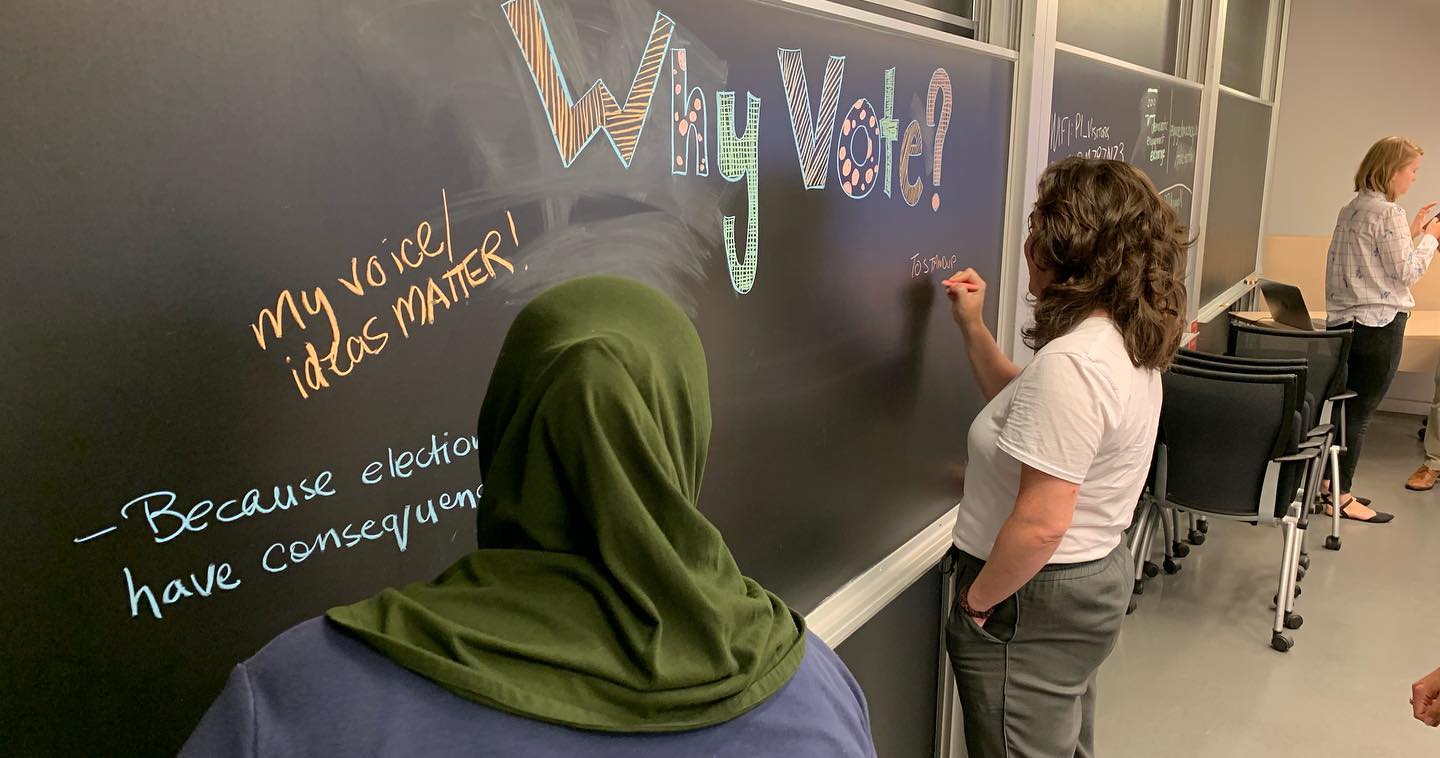

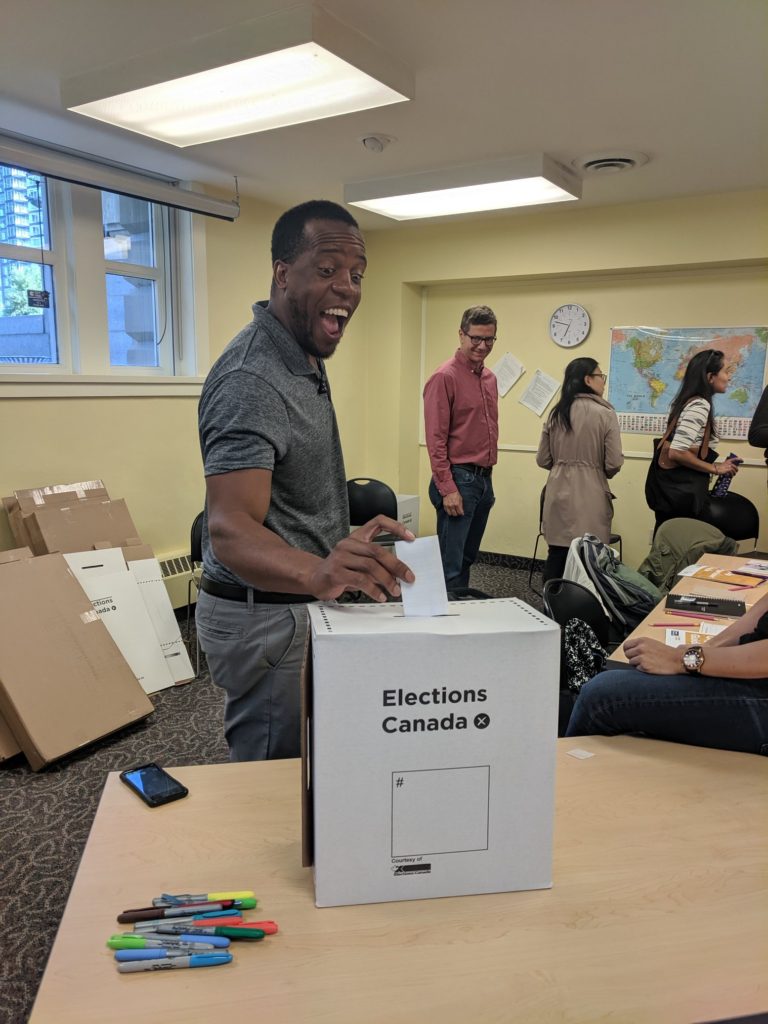

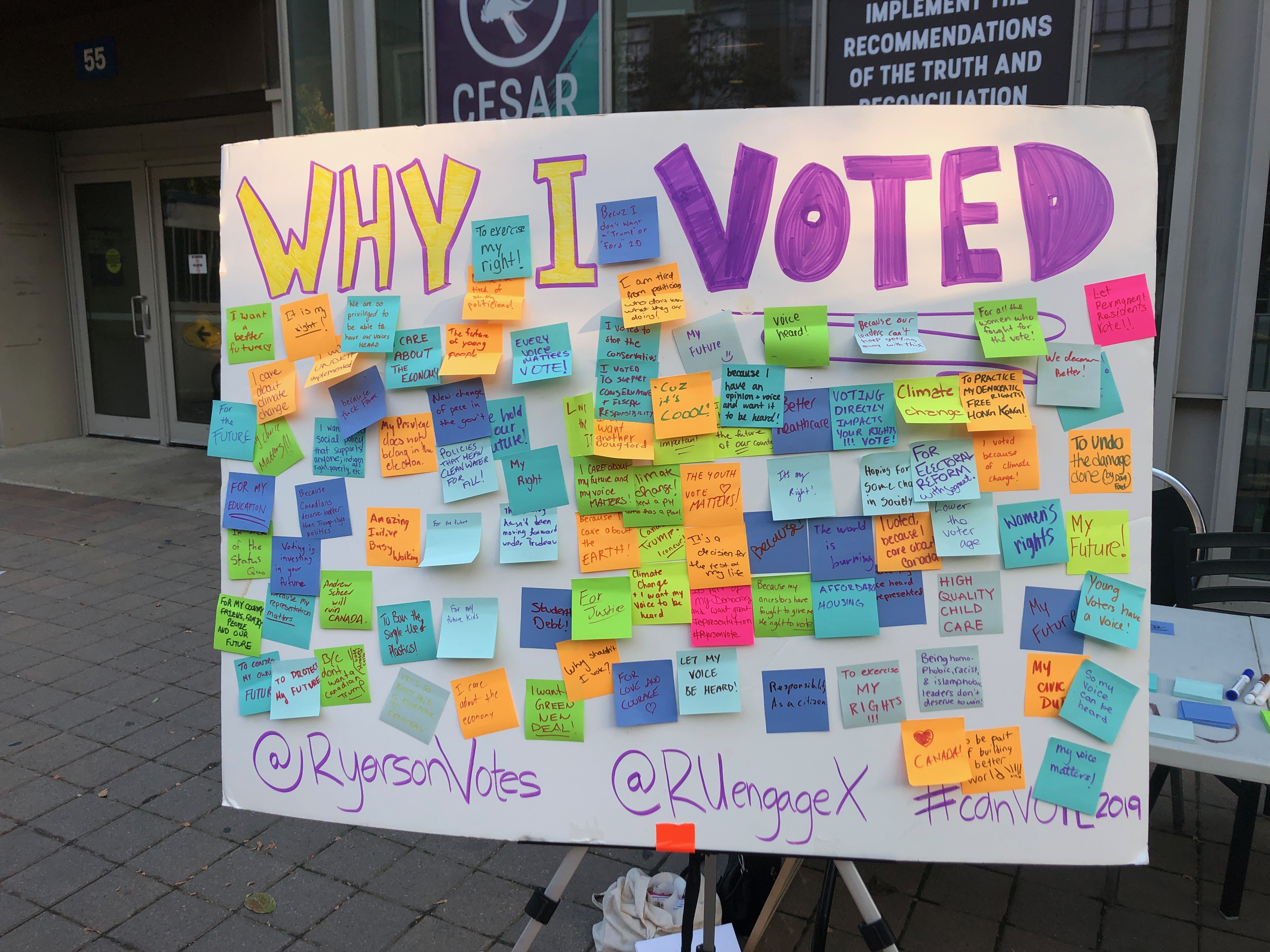

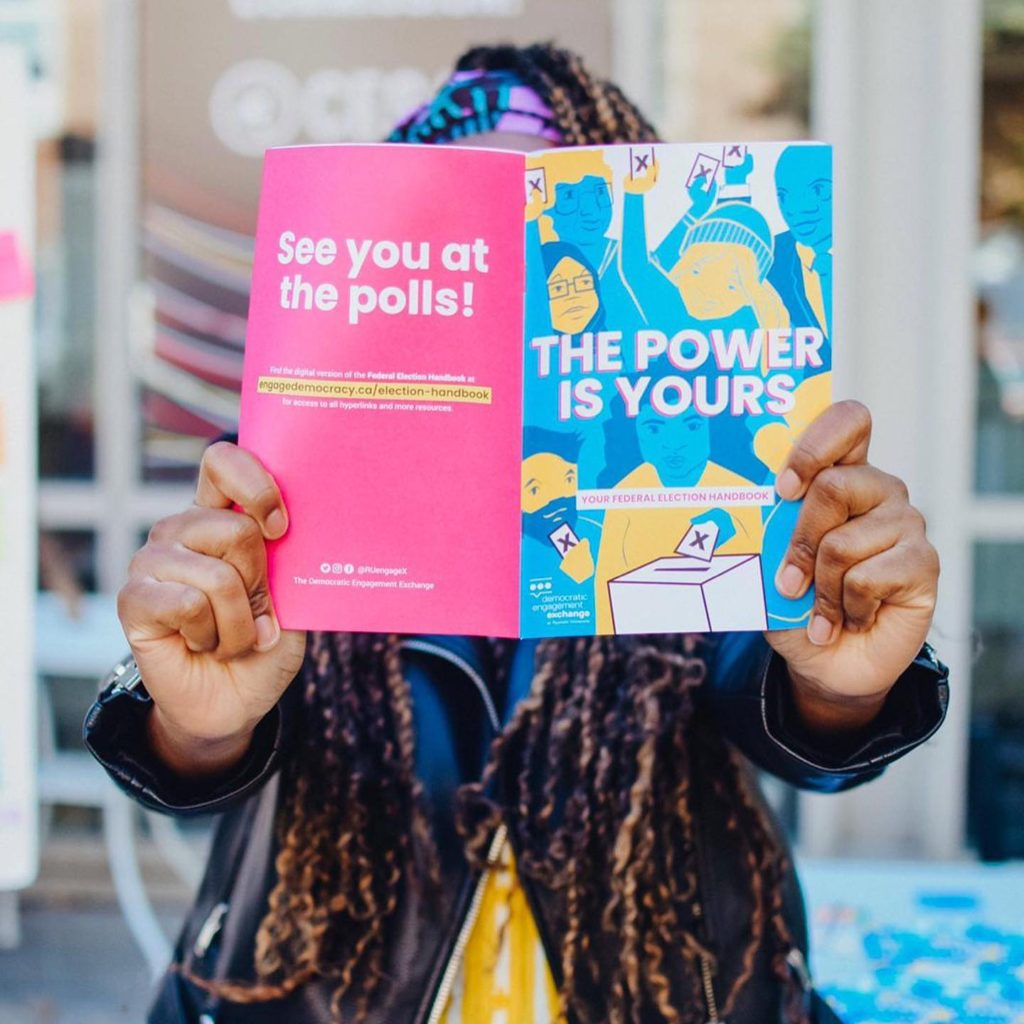

Illustration by Charlotte Reed

Illustration by Charlotte Reed

In tomorrow’s election millennials and Gen Z could, quite literally, decide the outcome of the election. These two generations (ranging in age from 18-38 years old) account for nearly a third of eligible voters in Canada. This fact grants them a great deal of power and responsibility in determining who’s elected and who isn’t. Unfortunately, despite their collective influence, it is not at all certain that Canada’s youth will take advantage of it. In fact, over the last several federal elections youth voters have had the lowest turnout of any age bracket. For example, in 2015 only 67% of youth aged 18-24 turned out to vote, with the 25-34 bracket only slightly ahead (but still behind all the others by at least 5%) with a 70% turnout.

In order to gain some insight into the research and efforts that have been made to help spark a shift toward greater youth engagement I spoke to Samantha Reusch, the Research and Evaluations Manager of Apathy is Boring, a non-partisan, youth-led organization whose goal is to educate Canadian youth about their democracy, shared her thoughts on this topical investigation.

Below are a few notable excerpts from the interview which highlight the complexity of the story behind these statistics, highlight ways that young people can best engage each other, and step up to Apathy’s challenge: “They think we won’t. Let’s prove them wrong.”

Anna: First off, what do you think the main reason is that people don’t turn out to vote?

Samantha: There’s a couple of different things. We tend to talk about the barriers people face to actually physically turning out to vote, uniquely, based on their identity and who they are. Those are really easily divided into access or “logistical” barriers, and motivational barriers.

When we talk about logistical barriers, we talk about the accessibility of polling stations and access to childcare and transportation. A lot of these are especially faced in rural situations or when you have accessibility needs. Logistics tend to be the priority of electoral management bodies, such as Elections Canada, to make sure their polling stations are physically accessible.

On the other side, we have motivational barriers, which include the perceived inaccessibility of elections and polls. Especially among young people, we often hear: “my vote doesn’t matter”, “all politicians are the same”, “I don’t like political parties” or, “I hate politicians.” These are the stories that we tell ourselves, that prevent us from wanting to engage with electoral politics. Young people themselves, or organizations like ours, have a unique advantage in tackling those barriers because we can use our existing relationships with people to make it more personal and overcomes barriers like people thinking “politics aren’t for me, they’re not about me.” A lot of people don’t connect the political jargon to their lives, so it feels removed and distant.

Another motivational barrier comes up when people don’t have enough information. They often say things like, “I don’t know enough to vote.” You can find all of that information online – but maybe you don’t feel like you have the civics background to understand it.

Those are the main ones, but especially with young people, we’re the largest voting bloc, but we’re also one of the biggest generations and the most diverse generations in Canadian history so what might be a barrier for one person, might not be for another, so it’s important to understand that when we’re looking at these barriers they’re unique to the person, there’s not going to be any one solution that will get everyone out to vote.

Anna: A lot of people I’ve talked to are very passionate about particular issues (for example, climate change or women’s rights) but find it difficult to associate that issue with a political party, and therefore choose not to vote. What would you say to those people?

Samantha: There’s one thing that we talk about a lot, especially when we talk about things like partisanship and how that falls on issues, which can be really complicated. We could have a whole hour-long conversation about figuring out if something is partisan. One way you can look at it is looking at problems that exist and then solutions that can be applied to them. For example, if you’re looking at a problem like the environment, the scientific community is in consensus that there is a problem that we need to address. Where I think politics can play a role is talking about the specific solutions. Depending on your ideology, you might have a different solution. Someone more oriented toward the right might look at market-based solutions vs. regulation. Your solutions might be different, but if we all agree on the problem at hand then it makes it a lot easier.

All of the misinformation right now is exacerbating this problem, because we’re not even focusing on solutions, we’re trying to frame our corner of the problem. This causes more disengagement and causes people to question what is even true. I think this is something that our generation is facing in a different way than previous generations.

Anna: What would you say to people who would rather protest, or sign petitions than vote?

Samantha: I think that you can do all of those things. I don’t think voting means that you can’t protest. There are many ways to have an impact on the issues that you care about. The way we think about it is that there’s an ecosystem of ways that you can have an impact. Organized movements have a lot of power, but that’s not the only route.

Voting is key to changing the system, so that young people see themselves reflected in it. It becomes this cycle of politicians who are on a campaign, who have a limited amount of resources and they ask “who can I reliably turn to turn out to vote for me?”, and so they go to their base and they go to get out their vote. Which makes sense.

Because young people turn out to vote in smaller numbers, candidates don’t rely on young people to vote for them, so they don’t invest resources or research in them. Which all contributes to this negative cycle. Part of breaking that cycle as a young person, is actually to – even if you live in a riding that’s been a stronghold for x number of years, and you don’t like that party so you say “oh well there’s no point because it’s just throwing out my vote” – just turn out to vote. Even if you don’t think you can impact the outcome in your riding, you’re actually having an impact on a bigger problem: which is the problem of politics in general, not paying attention to the voting block of young people.

Anna: Inevitably, of course, we won’t all see the outcome of the election that we want. How can we stop ourselves from getting overly discouraged, and losing faith in the system?

Samantha: Voting is a part of democratic engagement but it’s not the only tool available to us. You can organize a protest, you can sign a petition, you can call your MP (they are there to listen to you), you can try to influence the system in different ways. Or, if you really don’t like anyone, you can run for office! We often don’t think of that as a tool – but there are so many different things you can do. You can get involved in your local riding association, and I know that seems like a big hurdle – but you can just get involved in your local community organizations in your neighbourhood. Large scale systemic change is slow, so sometimes it’s hard to see the changes we want to see right away, but that’s why it’s good to get involved in these other spaces, where we can see and have a bit more of an immediate impact.

Anna: Many students at McGill and readers of our paper aren’t eligible to vote because they aren’t Canadian citizens or aren’t yet 18 years old, in what ways would you suggest these people get involved besides voting? In particular, at the time of a federal election?

Samantha: So much of democracy, even if you aren’t able to vote, is about how we engage each other. If you’re not eligible to vote but you still care a lot about issues that are impacting your community or city or country, just engaging with other people around you on those topics, talking about the problems and the solutions is a great way to get involved. Encourage other people to vote! You can go and volunteer on a campaign or in a community organization. And in general, engage with that ecosystem I mentioned – even if you can’t vote.

Things are already looking up this election: there was an astounding 29% increase in turnout to advance polls this past weekend. Strong voter turnout serves to hold the government accountable and ensure that all voices are represented and heard. The results of Canada’s 43rd federal elections will ultimately demonstrate whether millennial and Gen-Z voters have progressed in overcoming the barriers that have long-since kept them from voting.

Illustration by Charlotte Reed

Edited by Nikita Buchko