“I Came Here for a Better Life” – How Canada’s Immigration System Continues to Let Migrants Down

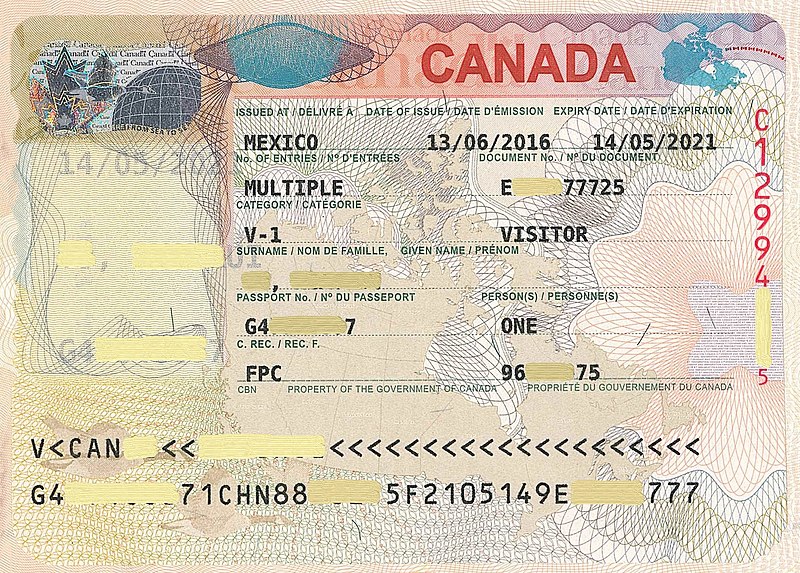

“Canada Visa” by ButcherC is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

“Canada Visa” by ButcherC is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Canada has long been dubbed a leading country in immigration and multiculturalism. Since policy changes to the immigration system in the late 1960s and the admission of 50,000 Indochinese refugees in 1979, many have considered Canada a reliable pillar in immigrant resettlement. This narrative has been at the forefront of the federal government’s marketing strategy, used to paint the nation as a welcoming and warm environment for potential migrants, and it is successful. The international community buys into this depiction of Canada, often in explicit comparison to the United States, with arguments urging Americans to learn from Canada’s open and welcoming immigration policy. However, this widely accepted vision of Canada’s system is far from the reality faced by thousands of migrants and refugees who hope to call this country home.

In actuality, Canada has been silently intensifying its immigration system since the late 1990s and early 2000s. The Immigration and Refugee Protection Act (2002), Multiple Border Strategy (2003), Safe Third Country Agreement (2004), and Protecting Canada’s Immigration System Act (2012) are all policies that have been approved in the last twenty years and limit routes for migrants and asylum seekers to Canada. In particular, the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act allowed for the creation of the Canadian Border Services Agency. This administrative body holds the power to detain migrants based on various factors including the failure to establish a person’s identity, the decision that a person is unlikely to appear for examination or admissibility hearing, or the classification of an individual as a threat to public safety.

If detained, individuals are sent to either one of three immigration holding centres (IHC), or to a provincial jail in circumstances where they cannot be sent to an IHC. The CBSA remains a loosely managed body; despite being a principal law enforcement agency in Canada, it has no independent oversight.

Immigration holding centres and the detention of refugees are largely a covert affair in Canadian civil society. Despite the succession of laws and funding that have been passed over the last twenty years, many Canadians are unaware of this side of the immigration process. Between April 2019 and March 2020, approximately nine thousand people were detained in Canada, including 138 children and infants. Numbers included children who are Canadian citizens with foreign-born parents. Detention is indefinite; Canada currently has no maximum time limit for being detained, meaning that migrants who are held by the CBSA often have no clue when they will be released. Canada has faced condemnation by several human rights organizations due to human rights violations regarding detaining children and indefinite detention periods.

Though categorized as an administrative process, Canada’s immigration system more closely resembles a criminal procedure. Detainees are treated like incarcerated individuals, with many reporting being handcuffed, searched, and subjected to solitary confinement and surveillance. Some have even reported being handcuffed merely to go to the hospital. Recounts of pain, frustration, depression, and anger are rampant among those who have experienced immigration detention. One man, Abdirahman Warssama had initially come to Canada from Somalia in 1989 after members of his family were murdered in his home country. Despite being allowed to stay on humanitarian grounds, the CBSA imprisoned Warssama in 2010 for nearly six years in a maximum security prison in Ontario and attempted to send him back to Somalia. Since his release, he has been pardoned by the federal government, but that does not erase the psychological abuse he endured in prison. Warssama now holds permanent residency in Canada, but fears the CBSA will detain him again in the future. As Warssama stated, “When I was in jail, I’d think, this is not Canada. I came here for a better life”. His sentiments are shared by a myriad of migrants and asylum seekers who face disillusionment upon coming to Canada under the pretense that they will be welcomed with open arms.

Following detention, harsh conditions result in further distress, as migrants experience heightened depression, anxiety, PTSD, and other mental health problems. In the past twenty years, seventeen people have died in detention. Most recently, a woman died by suicide in the Surrey IHC in December 2022. Another man, Bryan Stone, also committed suicide in the Laval IHC in January 2022. Stone had already attempted suicide four days prior to his passing, and was supposedly under a 24-hour suicide watch at the time of his death. Over the years, the CBSA has followed a pattern of failing to disclose sufficient information regarding deaths in IHCs and prisons, leaving families and human rights groups frustrated and angry. While the burden should not fall on them, many of these preventable deaths are only brought to the media by families who want these tragedies to reach a wider audience.

In the past year, the provincial governments in British Columbia, Manitoba, Nova Scotia, and Alberta have all announced that they are terminating their contracts of imprisoning migrants. Although a step in the right direction, it is not enough. Currently, Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick, and Saskatchewan all hold contracts with the federal government, in which they are paid to keep migrants in provincial jails. The B.C. Civil Liberties Association (BCCLA) has called on the CBSA to opt towards a ‘rights-affirming’ approach rather than detention, where migrants can continue to work, live in communities, and have access to immigration and status support while they wait for their documents to process.

With a relatively low birth-rate and aging population, Canada needs immigrants. And with announcements such as the goal to bring in approximately 432,000 new permanent residents by the end of 2022, one must question why some migrants continue to be dehumanized in the Canadian system. This is a tough question, with no honest answer. While certain groups point out Canada’s potential lack of capacity to support new migrants, Canada needs to focus on strengthening the systems it already has in place. Canada must ensure that the message it portrays of being open to immigrants aligns with appropriate measures to support them; immigration holding centres should not be a solution to a lack of resources. As a spotlight is shone on IHCs and the CBSA’s treatment of migrants, the Canadian government will find itself under increasing pressure to address the ongoing crisis. Federal and provincial governments must take the necessary steps to ensure more lives are not lost through immigration detention practices and live up to the standard of excellence that Canada portrays to the rest of the world.

“Canada Visa” by ButcherC is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Edited by Derya Ekin