International Law is Failing the South China Sea

USS Blue Ridge (LCC 19), and CNS Qilianshan (LPD 999) of the People's Liberation Army (Navy), participate in a joint search and rescue exercise in 2015. (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist Seaman Jordan KirkJohnson) https://bit.ly/2lX9uRj

USS Blue Ridge (LCC 19), and CNS Qilianshan (LPD 999) of the People's Liberation Army (Navy), participate in a joint search and rescue exercise in 2015. (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist Seaman Jordan KirkJohnson) https://bit.ly/2lX9uRj

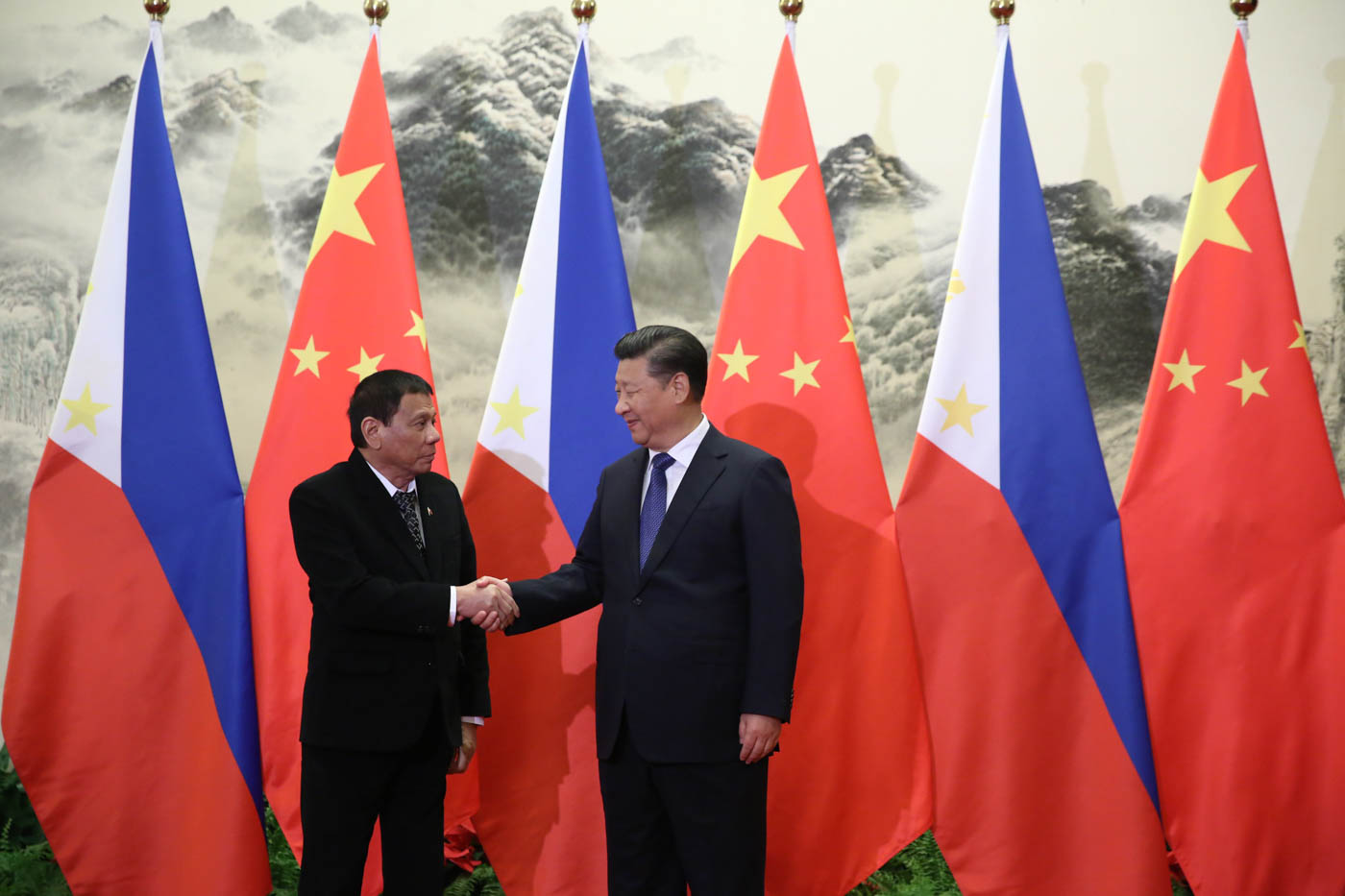

When Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte and Chinese President Xi Jinping met in Beijing on August 29, expectations were high that progress would be made on the South China Sea territorial dispute. After all, under mounting domestic pressure, Duterte had promised—for the first time—that he would bring up the 2016 arbitral tribunal ruling during his meeting with Xi. The 2016 ruling made by the Permanent Court of Arbitration under Annex VII to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) ruled in favour of the Philippines. It established that there was no legal basis for Chinese claims of historic rights to territory based on the Nine-Dash Line and that China had breached its obligations under the Convention on the International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea (COLREGs). Despite the ruling, China has continued to assert its claims to more than 80 percent of the South China Sea, building military facilities on contested territory and amassing a navy of more than 300 ships: the largest in the Asia Pacific. Less conventionally, it has employed a large so-called “maritime militia of well-equipped vessels” disguised as beguiling fishing vessels that patrol, resupply, surveil, and provoke incidents.

In the meeting, Duterte called the ruling “final, binding and not subject to appeal”, to which Xi responded by falling back on a familiar rhetoric of non-acknowledgement. Most recently, however, Duterte reneged on his commitment to the ruling after Xi promised a 60-40 sharing scheme in oil exploration favouring the Philippines. It is clear that international law so far has tried—and failed—to restrain Chinese advances in the South China Sea. Confidence-building measures (CBMs) currently in place must be adapted in recognition of an increasingly hegemonic China lest the rules-based order face continued erosion and smaller economies in Southeast Asia pay the price.

The main framework guiding South China Sea dispute management resides with the potential ASEAN-China Code of Conduct (COC). Though first discussed in 2014, China only began to take its approach towards the COC more seriously in late 2016 in an attempt to divert judgement from its rejection of the arbitral tribunal ruling. Chinese participation in COC negotiations have since come to serve a dual purpose as well—greater engagement between China and the ASEAN countries bolsters the narrative that disputes in the South China Sea are purely regional in nature and that foreign intervention is unnecessary. In August 2018, ASEAN and China endorsed a single draft negotiating text for the COC. In the draft, there was agreement on the need to establish a rules-based framework and work within international norms—interpretations of such broad terms, however, have bred room for what seem to be irreconcilable disagreements between claimant countries. For example, Vietnam has called for bans on the construction of artificial islands and the deployment of defensive weapons such as surface-to-air missiles. China has already done both. Vietnam and Indonesia have also jointly called for respect of coastal zones of maritime states, including their 200 nautical mile exclusive economic zone (EEZ), of which directly trespasses on China’s infamous Nine-Dash Line. Undeterred by their differences, the 11 parties consolidated the draft and performed a first reading on July 2019. Senior officials of each country will next meet on October 2019 to discuss how a second reading would proceed. Xi has even unilaterally called for the COC to be signed by 2021.

Despite what is perceived as progress, the COC is fundamentally flawed as a vehicle for dispute management. Notably, not all members of ASEAN are claimants to the South China Sea, even though ASEAN as a whole is involved in the COC process. Of the ten countries party to ASEAN, only four officially consider themselves claimant states, including Vietnam, Brunei, the Philippines, and Malaysia, with Indonesia an ambiguous fifth. It is difficult to fathom a world in which overlapping claims to seabed and waters can be effectively resolved when one side of the negotiations is inherently fragmented in their interests—and the other is China. First, this leaves both claimant and non-claimant ASEAN states vulnerable in negotiations with strongman China, the latter of which exploits cleavages in ASEAN’s negotiating stance. Second, with ASEAN negotiating as a whole entity, non-claimant states are dragged into disputes they have no part in and claimant states divide what is supposed to be the “One Vision, One Identity, One Community” that is ASEAN with their overlapping claims. How are states to fight collectively for their claims when their claims contradict one another?

Furthermore, the COC is fundamentally limited in what it can achieve. The COC must be recognized for what it is—a dispute management framework. It is not a dispute settlement mechanism. A final resolution of sovereignty claims and maritime boundaries under the provisions of UNCLOS could be “many years away” according to the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS). Therefore, all sides must approach COC engagement “without prejudice to the final settlement of claims” and emphasize that any agreement would have “no impact on the parties’ current legal positions towards the disputes”.

It is evident, though, that claimants’ actions outside of COC engagement nullify such prescriptions entirely. This has created something of a “two-track path” in South China Sea policy, wherein various confidence-building measures, such as the COC, are undermined by “confidence-eroding” activities perpetrated by claimants, such as Vietnam’s building of outposts on contested water and when the Chinese Coast Guard forced the breaking of the tow line of an Indonesian vessel within Indonesia’s EEZ. The ineffectiveness of current CBMs at constraining their parties may mask and even accelerate such confidence-eroding activities.

And it’s not just the COC. Various other CBMs that supposedly regulate activities in the South China Sea fall victim to the same narrative of ineffectiveness. The Chinese Coast Guard, People’s Liberation Army-Navy (PLAN), and maritime militia vessels continue to regularly violate Rules 2, 6, 7, 8, 15, and 16 of COLREGs, thus breaching Article 94 of UNCLOS. This was evident, for example, when China operated “in a dangerous manner causing serious risk of collision to Philippine vessels navigating in the vicinity of Scarborough Shoal”. It was also proven and condemned by the Permanent Court of Arbitration in 2016. Further, the Code for Unplanned Encounters at Sea (CUES), another agreement frequently applied to South China Sea disputes, lacks binding character and does not apply to coastguards, even though most incidents involve coastguards and other maritime law enforcement vessels.

There may be relevant precedent for restraining China as it continues to pursue various confidence-eroding activities in the South China Sea. One interesting precedent is the Guyana v. Suriname arbitral award from September 2007. Seven years earlier, two Surinamese patrol boats entered a disputed maritime zone and ordered an oil rig and a drill ship operating under Guyanese licences to withdraw. This, the tribunal decided, “seemed more akin to a threat of military action rather than a mere law enforcement activity”, thus ruling in favour of Guyana. The case highlighted first the existence of a threshold between law enforcement measures and threats or uses of force prohibited by article 2(4) of the UN Charter, and second, that it is a very low threshold. Given China’s more provocative actions, including the sinking of Vietnamese and Philippine boats earlier this year, it is clear that such a threshold has long been crossed.

More recently, and perhaps more relevant, in the Arctic Sunrise case brought forth by the Netherlands against Russia at International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (ITLOS), Russian authorities seized the Greenpeace ship, Arctic Sunrise, flying the Dutch flag in international waters within Russia’s EEZ, citing piracy and hooliganism from the crew as justification. On November 22, 2013, ITLOS ruled that the ship and its crew should be released immediately, in favour of the Netherlands. In 2015, the Permanent Court of Arbitration unanimously ruled that Russia had violated UNCLOS and required that it compensate the Dutch. Russia, like China in the South China Sea, vehemently ignored the ruling, and yet, in May 2019, the two countries issued a joint statement using language reflective of the 2016 South China Sea arbitral tribunal ruling wherein Russia agreed to pay compensation despite its previous non-compliance.

The tricky thing is, UNCLOS operates most effectively when there are clearly delimited maritime borders. However, the delineation of such borders arises from UNCLOS itself. This is what has trapped the South China Sea in what seems to be interminable dispute; it is this fundamental catch-22 that accounts for the failures of international law in restraining China. CBMs within this context moving forward must therefore come with more teeth.

However, it shouldn’t come with greater patrol from non-claimant states, such as the U.S., which continues its freedom of navigation operations (FONOPs) incessantly while touting virtues of a “whole-of-government-approach” to protect a certain rules-based international system under UNCLOS, of which itself has not ratified. To do so smacks of hypocrisy, especially seeing as China, no matter how unlawful, has at the very least ratified the convention. Continued FONOPs serve little purpose but to enrage an aggressive China and prompt further confidence-eroding activities to the detriment of Southeast Asian nations.

Future agreements must come with an understanding of such dynamics at play, and as the 11 countries meet next month, this must be a priority. For example, Jay Batongbacal, associate professor at the University of the Philippines College of Law and director of the university’s Institute for Maritime Affairs and Law of the Sea, suggests that CBMs should have clear action points that are publicly reported on and subject to independent verification by third parties, and there must be an active and standing convening mechanism immediately upon outbreak of an issue requiring concrete and visible action. Whatever their form may be, such CBMs must be leveraged to their fullest extent. Until then, international law will continue to fall by the wayside, engulfed by the murkiness of the very sea it governs.

Edited by Helena Martin and Alec Regino