Irish Reunification and the Irony Behind it

In January 2019, Theresa May’s Brexit withdrawal agreement was rejected by the House of Commons in the largest defeat in British political history. A third of Conservative MPs voted against the deal, many because they did not like provision about the “backstop”: a measure designed to prevent a hard border, featuring checks on immigration and customs, between Northern Ireland and Ireland. The backstop needs to be understood within the wider context of Anglo-Irish relations going back centuries, from the Act of Union in 1800, the Irish War of Independence, the Troubles, and the 1998 Good Friday Agreement.

The UK has always been the dominant partner in this relationship. However, in this centennial year since the outbreak of the Irish War of Independence, Ireland has now become the dominant partner and may finally, through Brexit and the backstop, achieve what centuries of conflict could not: the long-sought-after goal of Irish reunification. It is highly ironic that this has all come about at the hands of the Conservative Party, which supports Northern Ireland remaining part of the UK.

The Question of Home Rule

In 1800, Ireland was incorporated into the United Kingdom, by an Act of Union passed by both the Irish and UK Parliaments. Both institutions were Protestant-dominated, while the majority of the Irish population was Catholic; the latter bitterly resented the Union, which they felt undermined their cultural and religious identity.

Throughout the 19th century, the British government feared the majority-Catholic population of Ireland, because the latter held their allegiance to the Pope in Rome and not to the British monarchy. Thus, the Irish were seen as a disloyal part of the UK population, leading to repressive British measures to control them. As part of these measures, Catholics held very few rights and suffered discrimination in land ownership and the franchise. It is unsurprising, then, that British rule proved unpopular, causing Ireland to revolt six times prior to the Irish War of Independence in 1918.

The British solution to the discontent in Ireland was Home Rule, under which Ireland would remain part of the UK, but receive its own parliament with a limited number of devolved powers. Home Rule proved to be a divisive issue in British politics. The Liberals introduced a Home Rule Bill in 1886. However, this caused a large number of anti-Home Rule MPs to split off from the Liberals; these “unionist” MPs would eventually merge with the Conservatives, giving it its present name of the Conservative and Unionist Party.

Home Rule was rejected by Irish Nationalists because they supported an independent united Ireland. However, nationalism within Ireland held limited appeal; instead, the pro-Home Rule Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP) held a majority of Irish parliamentary seats. In 1914, Home Rule was finally passed on its third attempt by the Liberals. However, Ireland contained a substantial Protestant minority in the northern counties, who feared their identity would be attacked by a Catholic Irish parliament. The Protestants favoured continued direct rule from the UK Parliament, a position known as Unionism. Indeed, in 1914 the Unionists, supported by the Conservative Party, were prepared to risk civil war to prevent Home Rule. The outbreak of World War I forestalled such a conflict, as both Nationalists and Unionists supported the war effort to win support for their own respective goals.

The nationalist Irish Republican Brotherhood sought to take advantage of World War I to stage an armed uprising and achieve independence. The uprising occurred on Easter Day 1916, but was crushed by British forces within a week. The Easter Uprising had little support amongst the Irish population; however, the British decision to execute the leaders, thus making them martyrs, caused Irish public opinion to swing away from Home Rule and toward nationalism.

The War of Independence

This shift in Irish public opinion can be seen at the 1918 UK General Election, when the once-dominant IPP was destroyed and replaced by the nationalist Sinn Féin. The only part of Ireland which did not return any Sinn Féin MPs was the northern counties, who elected Unionists. Rather than take their seats in the UK Parliament, the Sinn Féin MPs met in Dublin on January 21st, 1919. They declared their assembly to be the sovereign parliament of Ireland, the Dáil Éireann, and issued a declaration of independence, which Britain rejected. This led to the start of the Irish War of Independence.

When neither side was able to achieve a decisive military victory, they decided to negotiate an end to the war. In the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1922, Ireland was granted dominion status, meaning it had only limited sovereignty and was still subordinate to the UK Parliament. Ireland would declare its full sovereignty in 1937, a move which would not be resisted by the British. The Irish Constitution of 1937 contained a commitment to a united Ireland, but this vision of the Nationalists was not realised. The Protestant-dominated northern counties received the right to unilaterally opt out of the Irish dominion and chose to do so; the six counties would form Northern Ireland, which remained part of the UK.

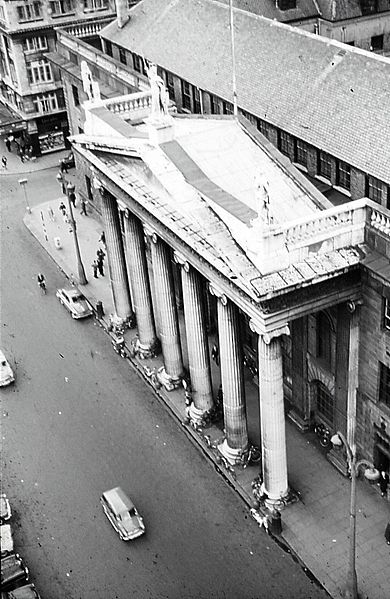

In 1920, Northern Ireland was granted its own devolved bicameral legislature, the Northern Ireland Parliament (also known as Stormont, after the area of Belfast where it is located). At the time, this arrangement was unique in the UK; Wales and Scotland would not receive their own devolved administrations until 1997. Northern Ireland remained firmly under the grip of a Unionist government, which politically and socially repressed the Catholic minority, who made up around a third of the region’s population. For example, elections to Stormont used first-past-the-post, a system that favours the majority population. In addition, seats were gerrymandered to ensure Protestant majorities. Catholics were also subject to discrimination in employment and housing, resulting in burgeoning Catholic ghettos.

The Troubles & the Good Friday Agreement

In 1969, a short-lived Catholic Civil Rights movement was overtaken by increasing Unionist violence, which helped trigger the armed campaign of the nationalist Irish Republican Army to achieve reunification by violence. This violence developed into the “Troubles”, a euphemism for a 30-year-long bloody conflict in which 3,600 people lost their lives. Stormont was suspended; the UK parliament took direct responsibility for handling the conflict and deployed the British Army to try and restore order.

The Troubles concluded with the Good Friday Peace Agreement of 1998. The Agreement restored Stormont, which would use single transferable vote (STV), an electoral system in which candidates compete in multi-member seats to achieve more proportional representation. In addition, any government would have to contain both nationalist and unionist parties, with cabinet posts divided proportionally according to party strength.

With respect to the status of Northern Ireland, Ireland amended its constitution to drop its commitment to a united Ireland. However, the Good Friday Agreement established “the principle of consent”, which meant that Northern Ireland would only remain part of the UK as long as the majority of the population supported this option. The Agreement states that if the UK Minister for Northern Ireland, feels that the majority no longer support the continuation of the Union, then the Minister has to call a border poll on reunification. Should the majority vote for reunification, the Agreement imposes a legal responsibility on the UK government to enact the result. The Unionists were happy with the “principle of consent”, as the majority in 1998 favoured the continuation of the Union; however, the door was opened to realizing the Nationalists’ dream.

Brexit

In June 2016, the UK voted to leave the European Union (EU), yet Northern Ireland voted to remain. After Brexit, the only land border between the UK and EU will be between Ireland and Northern Ireland. As the UK is leaving the EU’s single market and ending freedom of movement (the rights of EU citizens to live and work in another EU country without a visa), setting up passport and customs checks across this border would seem necessary. However, neither the EU or the UK wishes to see the return of a “hard” border, as an open border is perceived as a way of neutralizing issues of identity. Yet, an open border is not mandated in the Good Friday Agreement. It is a normative belief held by all sides that an open border would prevent the reemergence of identity issues in Northern Ireland and a return of the Troubles, but it is not a legal necessity.

According to the withdrawal agreement, if the UK and EU fail to agree on their future relationship by the end of 2020, then, to keep the Irish border open, the “backstop” will be activated. Under the backstop, the UK will remain part of the EU customs union, and Northern Ireland will remain part of the EU single market for goods. This arrangement, which separates Northern Ireland economically from the UK and leaves the UK as a rule-taker from the EU, could last indefinitely, according to legal advice.

In 2017, Stormont collapsed after Sinn Féin withdrew from the governing coalition with the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP), a right-wing hard-line unionist party, accusing the latter of mismanaging an expensive renewable energy scheme. Despite two years of negotiations and a snap Assembly election, Stormont has remained inactive with no end in sight. Therefore, Northern Ireland’s major political institution has been unable to play a role at this crucial time, when the future status of Northern Ireland is being decided. Meanwhile, the only group representing Northern Ireland in London is the DUP, currently in a confidence-and-supply agreement with the minority Conservative government. The DUP only won 36 percent of the Northern Irish vote in the 2017 general election and are not representative of all of Northern Ireland’s views. (Sinn Féin also won Northern Irish seats, yet they abstain from taking them, as they refuse to swear the required oath of loyalty to the monarchy.) As the DUP are unionist, they disapprove of the backstop that will separate the UK from Northern Ireland in regulations, as do many of unionist Conservative MPs. As a result, the DUP and unionist Conservative MPs voted down the withdrawal agreement.

Where now?

After the withdrawal agreement was rejected, the House of Commons approved an amendment that called for the backstop to be replaced by “alternative measures”. However, the EU has insisted the backstop cannot be changed. In addition, it is not clear if “alternative measures” exist; if they did, surely they would have been discovered and agreed upon in the negotiations. With an impasse over the withdrawal agreement, due to a backstop that the EU refuses to change and House of Commons refuses to accept, it appears increasingly likely the UK will leave the EU without a deal.

Meanwhile, the fact that Northern Ireland is being removed from the EU against its will, as well as the limited representation it has received in the Brexit process, means that polls are starting to show a shift in favour of reunification. The average result is currently 50 percent unionist among the population of Northern Ireland, a shift from the long-standing clear unionist majority. With the continuing problems with Brexit, there is every possibility that it may shift decisively in favour of reunification. This and the “principle of consent” may mean that, in a few years, the desires of the Nationalists may be achieved.

The normative belief of an open border may be about to achieve for Nationalists what armed conflict has not: a reunified Ireland. Alternatively, if the deadlock over backstop leads to the UK crashing out without a deal, the Nationalists will have the satisfaction of being the cause of the UK’s economic ruin. The greatest irony in this affair, however, is that the Conservative and Unionist Party, who were prepared to go to war in 1914 to prevent Home Rule, may through their actions bring about Irish unification.

Edited by Koji Shiromoto