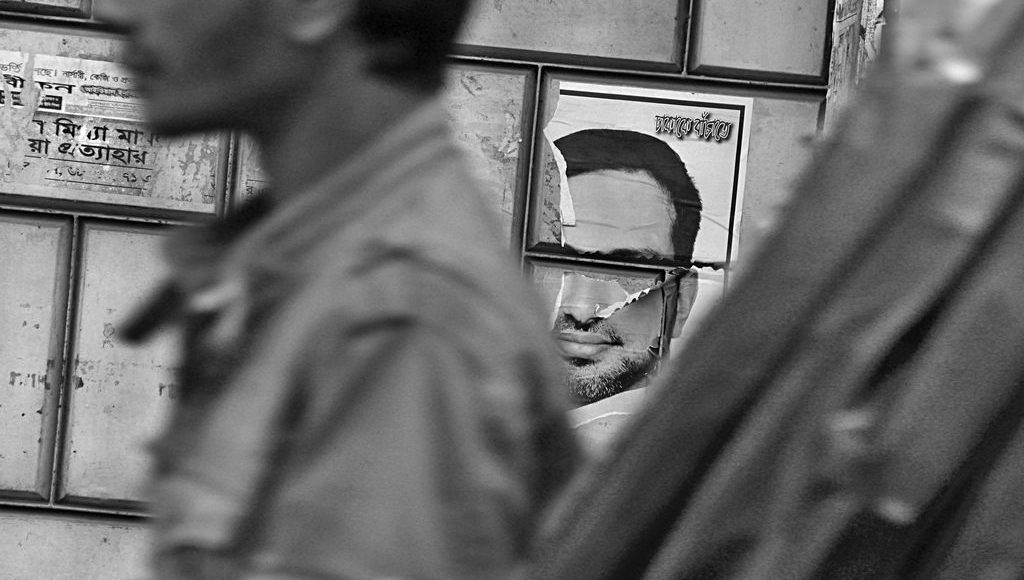

Is Bangladesh’s Deepening Political Crisis Sinking into Totalitarianism?

https://flic.kr/p/bo1Hag

https://flic.kr/p/bo1Hag

The hard-earned, sweet taste of independence Bangladesh gained less than 50 years ago is already being overpowered by the bitterness of constant internal political conflict between two historically rivaled parties. In the past year, political violence has climaxed, with two major protests occurring in the capital of Dhaka in April and August. On both occasions, peaceful protesters were targeted by the government. Furthermore, the degradation of freedom of the press in Bangladesh is blatant, with prominent journalists being brutally attacked, murdered, imprisoned, or mysteriously disappearing. The enduring political repression has caused the republic to take to the streets crying for reform, driving the current state of Bangladesh’s self-proclaimed democracy to extreme volatility. With elections around the corner, future actions could determine whether there is indeed hope for a true democracy in a country whose political identity is still transforming.

How Did We Get Here?

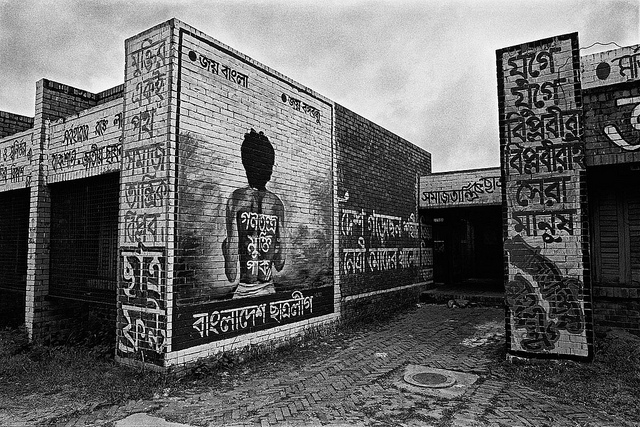

What was once known as East Pakistan became Bangladesh after a gruesome war for independence in 1971. The movement for Bangladesh’s self-determination ran parallel with this. The founding father of the republic, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, established the Awami league, which bases itself on the primacy of increased secularism as part of the Bengali identity. On the opposing end is the Bangladesh National Party (BNP), formed in 1978 by General Ziaur Rahman, defined by its more religiously influenced conception of Bangladeshi nationalism. The campaigns of both parties remain strongly connected to these individual leaders, and this extreme opposition between the Awami League and BNP characterizes Bangladeshi politics. In fact, the dominating hyper-polarization has entrenched politics into every aspect of society, especially in public life.

In its brief history, Bangladesh has experienced multiple uprisings in response to the failed attempts at installing a secure democracy. In 1983, Hussain Muhammad Ershad claimed the title as Bangladesh’s 10th president via a military coup against the former president, Abdus Sattar. Ershad’s rule was opposed by the BNP and Awami league, with many protests from student groups such as the Jubo League, a youth division of the Awami League. Protests against Ershad’s rule on the grounds of violation of democratic rights were viciously suppressed. Student groups were attacked, and some even killed. The student-initiated protests had sparked the formation of an alliance between the Awami League, BNP, and several other parties against Ershad. Noor Hossain, one of the students killed by the police during the 1987 protests, has become a symbol for the pro-democratic movement in Bangladesh. Historically, student protests have been a central force of political change in Bangladesh.

From 1987 onwards, in an almost poetically ironic turn of history, the widow and daughter of the founding members of the BNP and Awami league, Khaleda Zia and Sheikh Hasina, have fought each other in parliament tooth and nail, earning them the title as the “battling begums” (battling ladies). This bitter feud has lead to abuses of power and political violence from both sides, tainting the political sphere which now leaves no space for the general public to express dissent of any form. Consequently, hartals (general strikes) have become the primary means of representing their interests. However, after Hasina’s recent election without requisite oversight of a non-partisan caretaker government, the fervency of this bitter rivalry has declined. The current prime minister has actively suppressed opposition on all fronts and strategically obstructed the oppositional BNP party, with Zia, the party’s leader, in jail.

Today, many are concerned by the path that the current government is paving with its increasingly authoritarian behavior. The parliament has passed new laws that only further legitimize pre-existing Draconian legislation that non-state actors such as the UN Human Rights Council (UNHRC) and Amnesty International have strongly disapproved of as the laws violate freedoms of expression. Additionally, bureaucratic dysfunction and corruption have compromised basic aspects of public life, such as road safety. Domestic tension between the ruling party and the public has been fueled by the general impediments to living a secure and functional life caused by poor governance.

Where are we now?

The startling uptick in authoritarian behavior has reverberated with a nearly double increase in frequency of general strikes. Two major protests have occurred in the last year, both lead by student groups. In April, students protested against the unfair government quota system that allows only 44% of available positions to be secured on the basis of merit. Although this has been an issue previously protested in 2008 and 2013, the current government responded to these peaceful student demonstrations with tear gas and water cannons. Protesters were also attacked by a student wing of the Awami League. Some members of the ruling party viciously declared that the protests were the work of “razakars” (children of traitors).

Four months later, two high school students in Dhaka were killed in a car accident caused by a negligent driver. In response, on July 29th, large-scale protests from teens, parents, and other members of the public, calling for improved road safety began in Dhaka and spread outside of the capital and throughout the country within a week. Students at multiple universities organized strikes and cancelled classes. The protesters’ demands for road safety were recognized and supported by various domestic civil rights organizations. In Dhaka, police responded to crowds with tear gas, and rubber bullets and struck protesters with batons, ultimately detaining approximately ten students. The government also ordered schools and buses to shut down and blocked internet to suppress the demonstrations. Students and journalists attempting to cover the protests were attacked by pro-government youth leagues armed with sticks and machetes, leaving them badly beaten with broken equipment and phones. The protests purportedly persisted until August 10th. While the absence of enforced road safety measures itself legitimizes the actions of protesters, many believe that the protests were a product of accumulating public anger with the government’s corruption and intolerance of dissent. Nonetheless, the road safety protests have exhibited that the government’s doctrine of squashing the opposition has created a political environment toxic enough to politicize peaceful protests for public safety, into a violent standoff between the government and the dissenting people. The fact that Bangladeshis feel there is no other place but the streets to provoke change or express their demands speaks immensely to the current level of dysfunction in Bangladesh’s bilateral pseudo-democratic system.

At the end of September, the government passed the “Digital Security Act” which is aimed at improving cybercrime and “fake news”, but ultimately poses a great threat to not only press, but the general public’s freedom of expression – a freedom officially recognized by article 39 of the Bangladesh constitution. During the drafting of the act, organizations such as Amnesty International, International Freedom of Expression Exchange, and the UN have publicly criticized the broad and vague language of the legislation that would allow the government to fray from explicit punishable actions and target individuals more easily. The Digital Security Act also exhibits regressed freedom of expression in the severity of its punishments. Spreading “propaganda against the liberation war” (Section 8) and posting content that “targets religious sentiment” (Section 28) are punishable by 5 and 10 years of jail, respectively, and are non-bailable. With multiple secular activists and journalists attacked and killed in the last 2 years it is clear that there is already a dangerous and tense climate for the independent press in Bangladesh; however, this act legitimizes the government’s attempts at dominating public opinion.

Many citizens have also seen the recent war on drugs as a tool for political repression, creating an atmosphere of terror. In the country-wide crackdown of the viral drug Ya Ba, a mix of methamphetamines and caffeine, police have installed expedited judicial processes that skirt the rule of law by allowing law enforcement to convict a detained individual at the site of the arrest through mobile courts and with little requirement for evidence other than possession. Although some individuals believe that politically motivated extrajudicial killings have been tied to the drug war, the government denies that the police have killed anyone unjustly. Non-governmental organizations and independent media have pointed to over 100 deaths, and some everyday citizens believe that government-contracted killings have been concealed by false homicide reports that implicate individuals in drug-related crimes. This level of suspicion would be laughable in many western democracies, but some Bangladeshis have gathered evidence, such as audio recordings of opposition figures being murdered, to support these claims.

As mentioned before, numerous international watchdog organizations and governments have criticized the Bangladeshi government for its human rights abuses, but the government has not responded to international pressure. In fact, the efforts to curb domestic dissent has reached the extent of foreign and non-state actors. In 2014, Bangladesh passed the Foreign Donations Regulation Act, which hinders the work of independent NGOs by mandating government surveillance and allowing only government approved foreign aid, thus limiting foreign aid that is essential to organizations.

What is to come?

It seems as though the Bangladeshi government has let power retention surmount governance of its people, leading to a slippery slope of increased authoritarian behavior. When political repression has reached a certain extent, the government that justifies this does so for the sake of its own survival. As such, uproar and public anger could very well be a threat to government leaders’ lives if they lose their grip on parliament. At this dire junction, it is difficult to see where the turning point for Bangladesh lies in its future. The issues tied to increasingly authoritative governance, approaching a democratic dictatorship, are clearly pervasive, yet they have not proven severe enough to persuade the government to sincerely reform itself. Suppressing dissent is a vicious cycle that only induces more lawless behavior and unrest as citizens sense the diminishing legitimacy of their government, prompting further-increased authoritative behavior, and this cycle perpetuates. Such an unsustainable political future in an infant democracy is treacherous.

As of today, Bangladesh is posed with many arduous challenges that all call for immediacy. Climate change, the Rohingya refugee crisis, nuclear security, and military expansion are only a few of the larger issues that confront Bangladesh, not to mention the constant struggle towards development and economic growth to catch up with its subcontinental neighbors. However, in a political society where the government’s primary concern is gripping onto power by any means necessary, even at the expense of public freedoms and safety, these international issues cannot be addressed until domestic crises have subsided.

Despite Bangladesh’s grim political landscape, the country’s economy is thriving. This is largely in part due to its booming garment industry, boasting 8.76% growth in the sector since the last fiscal year and a GDP annual growth rate of 6.77% on average in the last 4 years. The Bangladeshi government has consistently pointed to this metric as an indicator of its success and assures itself that ongoing political unrest will not interfere with the country’s growing economy. Although the export industry has proven resilient in times of political distress in the last few years, rising domestic tensions still pose the threat of an economic downturn. In one respect, negative perceptions regarding Bangladesh’s oppressive government in the international realm impact foreign direct investment, which is crucial to the country’s growth and development. Large investors from Japan and Korea have bailed on multi-billion dollar investment plans in Bangladesh after reviewing the socio-political state of the nation during the turbulent 2014 election year. While the government does acknowledge the impact of political unrest on the economy, its official statistics do not point to serious losses. Independent economists have claimed that government-issued statistics underestimate the impact of the political unrest, not accounting for the barriers posed by traffic, stagnant consumer spending, loss in tax revenue, and capital flight. Furthermore, many economists have remarked that Bangladesh has grown below its potential because of political crises, distancing the country from its goals of poverty alleviation. The EU, one of Bangladesh’s largest trading partners, has already threatened to suspend trade privileges with Bangladesh in previous years, but the political crisis has only deepened since.

Regardless, the current development model of resilient growth in Bangladesh is being fiercely tried by the government’s increasingly authoritarian behavior. Deaf to domestic cries and international shame, perhaps the shock of an economic crash will wake the government from its power trip and compel necessary political restoration. But will Bangladesh be able to endure such a cost?

Edited by Shaista Asmi