Justice in Syria: There Should Be Some

Authoritarian President Bashar al-Assad of Syria has surpassed the country’s constitutional two-term presidency.

Authoritarian President Bashar al-Assad of Syria has surpassed the country’s constitutional two-term presidency.

Over a decade of war has left Syria in ruins. As the political elite perpetuates an exhaustive list of war crimes, justice for the victims seems to be just out of reach. Where transitional justice mechanisms have sought to enforce accountability and achieve justice for victims around the world, corruption within the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) prioritizes the geopolitical interests of powerful states at the expense of Syrian civilians.

President Bashar al-Assad’s oppressive tendencies, applied under an arbitrary state of emergency, were met with a series of nationwide pro-democracy protests beginning in March 2011. Choosing to respond with violent military backlash, the al-Assad regime, with Russian support, continuously escalated the conflict. Al-Assad has since promised to ethnically cleanse the country of the Sunni Muslim population, committing mass war crimes that have caused catastrophic civilian death tolls and millions of refugees as a result.

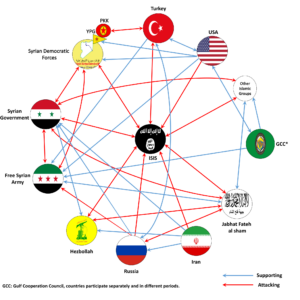

At its roots, the conflict in Syria is a civil war between the al-Assad regime and opposition forces. However, Syria’s geopolitical importance has solicited the attention of foreign actors. Opportunistic countries view Syria’s instability as a chance to increase their power in the Middle East, a region commonly associated with proxy warfare, where governments use external geographic locations to engage in conflict. Among al-Assad’s supporters are Russia and China, with Russia backing al-Assad’s actions with financial contributions and weapons.

Russia and China are far from the only foreign actors involved in the conflict. Al-Assad also uses non-state actors to aid his cause, including Iranian-backed Hezbollah, al-Qaeda, and the Islamic State (ISIS). On the other hand, the United States and Israel support the Syrian opposition forces and non-state actors such as the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF). Emerging from these strategic divisions are patterns of geopolitical proxy warfare between rivals, such as Russia and the US and Iran and Israel. The acute involvement of foreign actors is hugely problematic as it obstructs international justice. This geopolitical power struggle seems to take precedence over the dire fate of the Syrian people, with an estimated death toll surpassing 500,000.

Although the UN stopped counting casualties in 2016 due to the barriers to accessing information created by the conflict, there is an extensive archive of the widespread illegality of al-Assad’s actions throughout the conflict. Due to increased digitization, civil society and non-governmental organizations engage in mass documentation of the government’s crimes. The Syria Justice and Accountability Centre (SJAC) and the Syria Archive, for example, aim to preserve and protect documented evidence that could be used in future justice mechanisms.

Some Syrians risk their lives to reveal this evidence believing that corroboration of these crimes is necessary for a trial or truth commission. For example, a military defector known only as “Caesar” leaked over 50,000 photographs revealing evidence of torture, mistreatment, and illegal execution of civilians between 2011 and 2013. Six years after he published the photos, the International Center for Transitional Justice (ICTJ) released a report recognizing the Syrian regime’s use of forced disappearances as a tool of war. Abductees suffer similar fates to those in the Caesar photographs, and many have never been heard from again.

Despite the mass documentation of war crimes, international law fails to reach Syria directly because expected measures of justice and accountability, typically enforced by the international community, remain idle or blocked by Russia and China’s veto power at the UNSC. In most cases, war criminals are brought in front of the International Criminal Court (ICC) through a referral from the UNSC, with the latter petitioned to mobilize a human rights process at the international level. While Russia and China, members of the Permanent Five (P5) on the UNSC with unlimited veto power, are primarily responsible for blocking such a referral, their ability to do so highlights an essential flaw in current mechanisms of international justice. If accountability for a regime accountable for the highest number of documented systematic human rights violations in history hinges on the geopolitical interests of a few powerful countries, the structure of international justice needs to change.

Forced to confront the atrocities in Syria through non-traditional justice mechanisms, humanitarian assistance, truth-seeking, and legal accountability are circling the same avenues since 2011. These inadequate attempts at international justice work to maneuver around barriers provided by Russia and the UNSC, while some countries have issued international arrest warrants for al-Assad’s senior officials. While this is a step in the right direction, few are charged through universal jurisdiction. Unless Russia turns on al-Assad and withdraws its support, the international community has no leverage or avenue to pursue justice.

Syria presents an enigmatic case to transitional justice because of the conflict’s ongoing nature. Mechanisms like truth commissions usually respond to post-conflict settings and are most commonly associated with transitions to democracy, which is clearly not yet the case in Syria. Nonetheless, the conceptual underpinnings of transitional justice have expanded since its first phase of development after World War II. Most recently, transitional justice practices have evolved into a victim-centred approach and adapted mechanisms to varied local political and socio-economic needs; experts point to the possible implementation of local courts, such as those used in Rwanda. This advancement in the field proves that change to the system is likely to accommodate complex cases.

Policy experts widely accept that two things are required for justice in Syria: first, a peace agreement that includes the removal of regime leader al-Assad, and second, the implementation of a transitional justice process that would make war criminals answer for their crimes and address the social and economic repercussions of a post-conflict society. The ICTJ concluded their 2020 report on Syria with a list of recommended actions for the international community to take moving forward. This included encouraging the mobilization of civil society and grassroots movements to support those impacted by the conflict in Syria and calling on international institutions, such as the UNSC, to enact resolutions and refrain from vetoing efforts to send the case of Syria to the ICC.

Dependence on external actors whose motivations do not prioritize the needs of victims perpetuates the imbalance of political hegemony in the hands of the UNSC. The absence of a justice mechanism in Syria points to the performative nature of our international justice system, wherein geopolitical interests take precedence over the principles of justice. The international community’s actions during this crisis will impact future cases: either we reevaluate political power balances or crimes against humanity will continue to go unpunished.

Featured image: “Propaganda Poster” by Travel Aficionado is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0.

Edited by Alison Lee