Latin America’s Electoral Turn Towards Populism

9/12/07 Salon Blanco: Banco del Sur.

9/12/07 Salon Blanco: Banco del Sur.

2019 is a year of elections in Latin America with 6 countries—Argentina, Bolivia, El Salvador, Panama, and Uruguay—headed to the polls. Thus, it is worth noting the electoral regional trend by taking a look at the 2018 wave of elections which saw three of the biggest Latin American countries—Brazil, Mexico, and Colombia—electing new leaders that are populist in nature. Understanding this turn to populism from these three key electoral players can shed light on the future of regional politics in this upcoming electoral cycle.

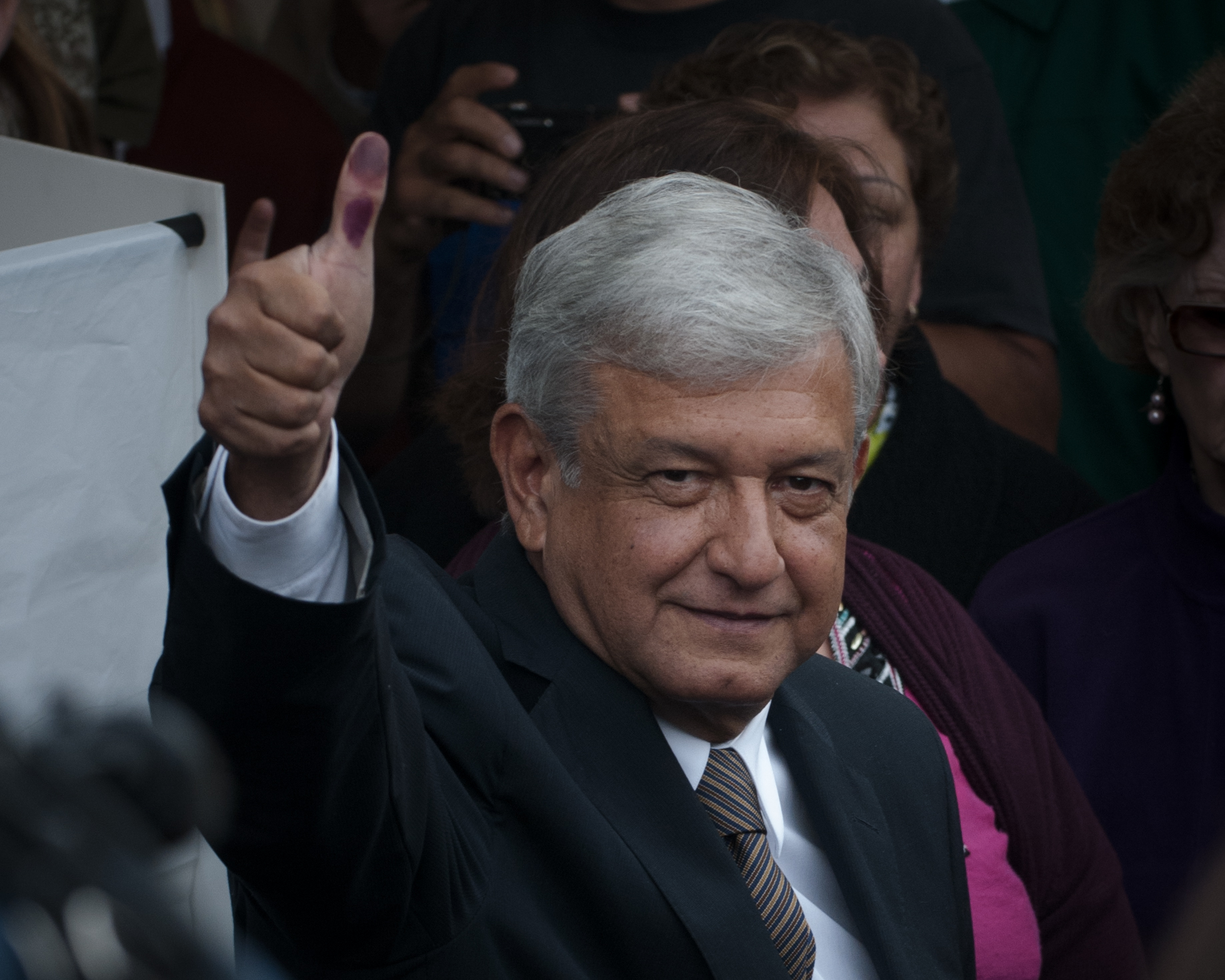

The newly-elected populist leaders in Colombia, Mexico, and Brazil come from both sides of the political spectrum. Colombia elected young, populist conservative Iván Duque who tapped into the citizenry’s dissatisfaction with the economy and a contentious peace treaty with the guerrilla rebels. Mexico elected Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO), who is on the left of the political spectrum, and whose campaign rhetoric focused on bringing representation to those in the country that were left behind by Mexico’s modernizing policies. Finally, in Brazil, we have the now-infamous far-right politician Jair Bolsonaro who promised to restore traditional Christian family values and clean-up the country from crime and corruption.

Both AMLO and Bolsonaro ran populist campaigns, promising to upend the political status quo after a period of unprecedented corruption revelations and intolerable crime levels. Both leaders tapped into an angry sentiment that helped them stand apart from the mediocre leadership of established parties, the PT in Brazil and the PRI and PAN in Mexico. But there end the similarities between these two populists.

Perhaps the most high-profile of the three due to his likeness to President Donald Trump, Bolsonaro has taken his role as a reformer very seriously for both good and bad. His government has already started implementing tax and pension reforms “that political economists have prescribed for the last 30 years,” but he regularly emits strong far-right rhetoric particularly against political correctness, LGBTQ Brazilians and indigenous land rights. AMLO, instead, has put his populist policy of “draining the swamp” at the forefront of his government by implementing massive wage cuts in government payrolls that have driven technocrats into the private sector. Insiders, however, are concerned that this radical approach might fill governmental institutions with “untested amateurs, rash ideologues and corrupt dinosaurs.” Finally, we have Duque, the youngest of the three, who has had trouble implementing his proposed reforms as he faces a fragmented parliament with over a dozen different political parties. Duque supported a referendum on proposals aimed at combating institutional corruption, but it had a low turnout which meant that it failed to gain enough votes for approval. Despite these hurdles, one thing is certain: the angry populist advocating for institutional change is likely to be a trend that will continue.

With the 2019 elections approaching throughout the rest of the region, we will likely see a similar pattern. This is largely due to two major factors sweeping the continent: an economic downturn and countless corruption scandals. In recent years, many of the countries’ economies have collapsed meaning dissatisfaction has risen across the continent. Even in countries where the economy has blossomed, we see a widened inequality gap with wealth being concentrated into the hands of the political and business elite. This is not lost on candidates who take a populist stance and capitalize on this dissatisfaction and inequality to appeal to voters. This rhetoric was particularly poignant during AMLO’s campaign where he sought to position himself as a candidate who was going to be able to close the gap between poverty and modernization in the interest of “the people”. We can see the likelihood of a similar situation in Argentina where the peso has “lost a third of its value in 2018, prompting protests against austerity measures and a staggering $57 billion bailout package from the IMF—the largest ever given by the international body.” Two rising contenders for the October election are incumbent President Macri, who sought to break from the populist ideals that have ruled Argentinean politics for decades, and former president Cristina Fernández de Krichner who epitomises the populist strain of the Peronist movement. If this trend proves to be right, we can expect a rise in support of Fernández or at least a stronger polarization between “Cristinistas” and “Macristas”.

Corruption is closely tied in with the populist narrative. These past decades, the region has seen an unparalleled amount of corruption scandals that spans governmental levels and transnational networks such as the Odebrecht scandal of 2015, which saw the company paying over $29 billion in bribes in exchange of contracts in over 12 countries in the region. In response, various candidates emerged that vowed to clean up politics against the pervasive problem of corruption. Bolsonaro, for example, painted himself as an anti-corruption crusader during his campaign, vowing to not institute those who have been convicted on corruption. By tapping into the cynicism and dissatisfaction of those disillusioned with the corrupt political establishment, populist politicians are able to position themselves as outsiders who are going to challenge the cycle of corruption.

Positioning themselves as anti-establishment outsiders is a key technique used by populist candidates, and certainly employed by Duque, AMLO, and Bolsonaro. By acting as the antitheses of the traditional parties, they are able to exploit the dissatisfaction and distrust of the population caused by corruption scandals and economic inequality for their campaign. AMLO, for example, promised to “end the corruption, the impunity, and the privileges enjoyed by a small elite,” while at the same time referring to the traditional PAN and PRI parties as the “power mafia”. Duque painted himself as being the representative of a new generation of leadership against the long-established political elite. The electoral success of these candidates point to a trend among the electorate of a rejection of the traditional political establishment which is undoubtedly going to bleed over into the region’s coming elections. Nayib Bukele, the president-elect of El Salvador, has already exemplified this trend. According to Brookings, “Bukele is the first candidate to win the presidency in 30 years who is not from the parties associated with the country’s brutal civil war—the right-wing Nationalist Republican Alliance (ARENA) and the left-wing Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN), still led largely by demobilized guerrillas.”

As five Latin American countries head to the polls in the upcoming months, it is important to acknowledge the electoral trends that are sweeping the region. Populism is emerging as an antidote for the growing low tolerance for corruption, the diminished trust in the political class among the citizenry, and dissatisfaction with economic development. Indeed, populism presents itself as an attractive alternative to the pitfalls of the status quo, but the cost of this turn towards anti-establishment candidates has yet to be assessed in the next electoral cycle.

Edited by Zoë Wilkins