LGBTI Rights in Latin America: A(nother) Pending Debt

In 2006, Guinness World Records named the São Paulo Gay Pride Parade –which was made possible by the federal government— the biggest pride parade worldwide. Photo by: Ben Tavener.

In 2006, Guinness World Records named the São Paulo Gay Pride Parade –which was made possible by the federal government— the biggest pride parade worldwide. Photo by: Ben Tavener.

On June 30th, the 17th edition of the Marcha del Orgullo Gay (Gay Pride Parade) took place in Peru. Like most years, thousands of Peruvians (Lima, the capital city, hosted roughly 50,000) who either belong to or support the LGBTI community, took to the streets of more than 14 cities across the country to reclaim the rights of this ostracized, extremely vulnerable sector of society. At the same time, demonstrators paid homage to all the human losses that the community has suffered through, such as the incident on May 31st 1989, when the Túpac Amaru Revolutionary Movement (MRTA) murdered eight homosexual friends who were having fun at a nightclub in Tarapoto. In light of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights’ long-awaited recognition of same-sex marriage as a legal right in January and the numerous pride parades that have occurred in the Americas, it is fundamental to reflect on the reality of human rights in a region where many people still believe in depictions of gay people as incurable perverts.

The development of the LGBTI rights movement across the continent is awe-inspiring. With the precedent of the United Nations’ protests against Cuban concentration camps for homosexuals in the 60’s, various activist groups in Latin America have joined their efforts to organize massive pride parades that transcend the local sphere and give hope to LGBTI people in the most ultraconservative regimes. In some cases, the events are even funded by governments and corporate sponsors. In 2006, Guinness World Records named the São Paulo Gay Pride Parade–which was made possible by the federal government— the biggest pride parade worldwide (with the New York City Pride March second on the list).

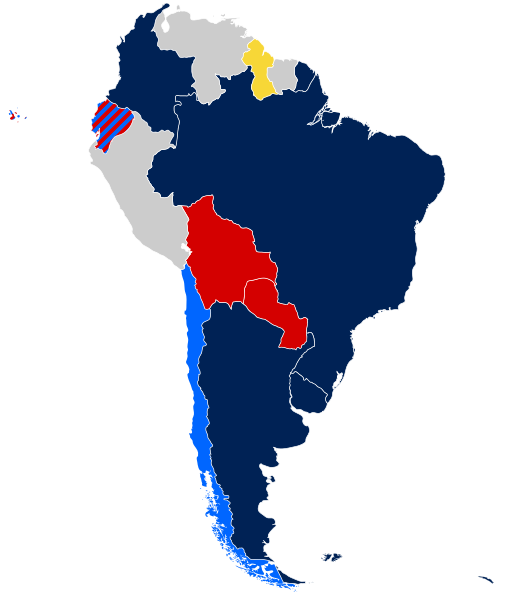

Needless to say, very few of us will remember circumstantial information such as the locations of departure and arrival, the total number of attendants, or the names of the celebrities who were present. However, if there is something we should retain in our memories, it is that behind the festive and quite moving manifestations that characterize the movement around the world, lies a condemnation of the pervading social denigration to which those who do not ascribe to the majority’s standards are subject. The truth is that, although there has been considerable progress (especially in South America, where countries like Argentina and Chile have legalized gay marriage), there is much left to do.

I have to confess that a few years ago, when the Peruvian press was only beginning to pay attention to the Gay Pride Parade, I knew very little about the history of the gay rights movement. Similar to other major landmarks in human rights history (such as the struggle for women’s suffrage and the civil rights movement led by Martin Luther King Jr.), it was only the persistent efforts of a handful of individuals that served as a catalyst for bigger undertakings.

It all started with the series of demonstrations baptized as the ‘Stonewall riots.’ At the end of June 1969, a New York pub called Stonewall Inn was the scene for the first manifestation of the LGBTI community against police raids that persecuted their members across the country. Despite the fact that those were times of social and political upheaval, openly homosexual people who frequented the pub –just like Emily Davison and Rosa Parks before them— decided to defy the status quo. Had it not been for them, many jurisdictions would continue to penalize homosexuality, and it would still be regarded as a psychiatric disorder. Beyond any doubt, activism (when exercised with responsibility) can have a great pedagogical effect insofar as it is capable of setting favourable precedents for the long-awaited change that seems closer and closer.

Surprisingly, in the Pre-Columbian period, the vast majority of indigenous civilizations were more tolerant and respectful of people who were perceived as homosexuals, as well as women. In the Caribbean and North America, many of the natives saw homosexuals as magical beings whose proximity would bring good fortune to their communities. Moreover, numerous anthropological studies have demonstrated that each tribe conceived sexuality according to its own culture. There was respect for bisexuality in the territory of Ecuador and men adopted typically female roles in certain domains of the Aztec Empire. In a similar vein, the erotic ceramics of ancient Peru (particularly those of the Moche and Chimu cultures) represent explicit scenes of homosexual intercourse.

It was only with European colonization and the cultural genocide that ensued, that homophobic practices were established. Historian Maximo Terrazos Contreras describes how “under the Inquisition, brought to Peru in 1569, homosexuals could be burned at the stake.” Crucially, the Catholic Church imposed the dogmatic belief that homosexual behaviour was both demonic and reprehensible. As a result, predominantly Spanish colonisers killed countless homosexuals of Amerindian background.

In Peru, the Political Constitution states that “No person shall be discriminated against on the basis of origin, race, sex, language, religion, opinion, economic status, or any other distinguishing feature” (Article 2, Fundamental Rights of the Person). Nevertheless, daily interactions evince that Peruvian society has a lot of trouble complying with such a guiding principle (that is, not making capricious distinctions between its members). There is no official registration of attacks and hate crimes against queer people and very few entities tinker with such conflicts. Two initiatives are Promsex (the Centre of Promotion and Defence of Sexual and Reproductive Rights) and the Observatory of LGBT Rights from the Cayetano Heredia University (UPCH), which have both maintained that perpetrators often torture their victims before killing them. All one would have to do is browse the thousands of hateful comments against LGBTI people on social media and to become completely demoralized. The disdain of some people is nothing compared to the brutality instilled in those messages: a sentiment nourished by a seemingly irreconcilable homophobia that has its roots in the patriarchal structure of society and the supremacy of Catholicism.

At this point, the only long-term solution to the problem is an education system that prioritizes gender equality and the creation of spaces for the acceptance and inclusion of sexual minorities. The same applies for patriarchy, ‘machismo’ (the idea that men are superior to women), misogyny, gender violence, and all the other social phenomena whose death toll increases every day. Those who oppose this radical change –for instance, the ultraconservative movement #ConMisHijosNoTeMetas (transl.: Don’t mess around with my children)— maintain that the so-called “gender ideology” will promote the “homosexualization” and the spiritual downfall of Peruvian children. For a population that largely ignores and fears the word ‘gender’, the only possible cure is an educational revolution that breaks away from heteronormativity, male chauvinism, and the stigmatization of the other.

One day, the dream behind the Marcha del Orgullo Gay will go from being a noble but repeatedly frustrated crusade, to a tangible reality that is celebrated in newspapers and life itself. In order to respond to the fair requests of the LGBTI community, there is no need for hypocritical speeches nor opportunistic political campaigns. What we need is both a legislation and an education system that deal with the marginalization of this human group that is as old as our species, and that will be with us until the end of it. Change will come. Until then, however, the concession of LGBTI rights will remain a(nother) pending debt.

Edited by Alec Regino

Angello Alcázar is an undergraduate student at McGill University pursuing a Joint Honours degree in Sociology and Literature.