Meet Keiko Fujimori, Peru’s Veteran of Corruption

Several high-profile publications, including The Economist, the New York Times, and The Guardian, have covered the 2021 federal elections in Peru. This coverage highlights that after losing her third election, Keiko Fujimori cried fraud without any evidence and attempted to override the votes of 200,000 Indigenous people. Her attempts failed, but they caused elites to question the legitimacy of the newly elected president Pedro Castillo. Most coverage of the Peruvian election naturally focused on recent events; however, any explanation regarding the events in Peru would not be complete without a comprehensive understanding of Keiko Fujimori’s background.

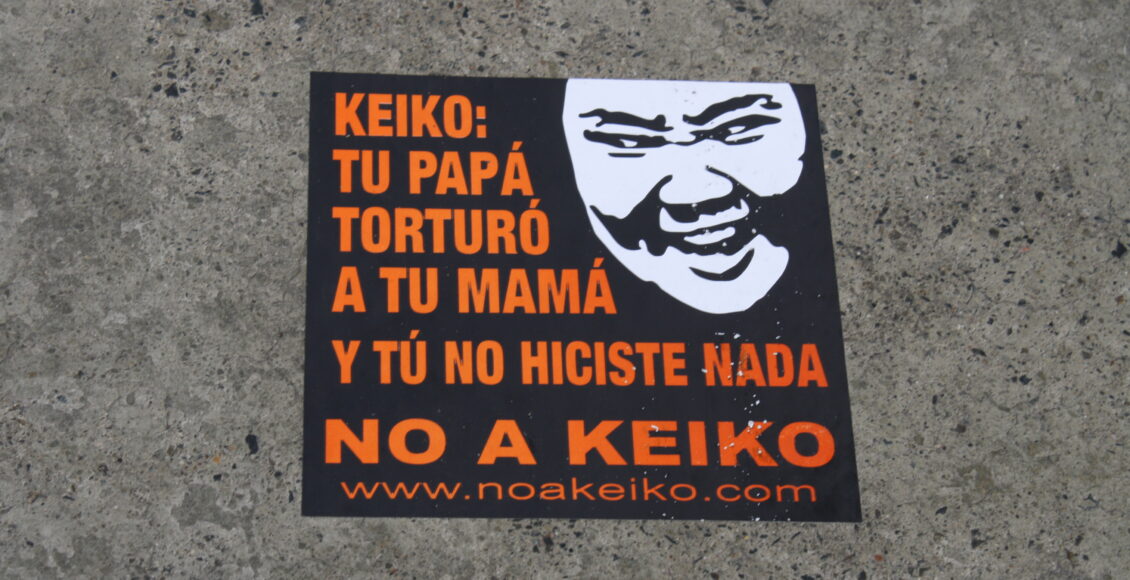

Keiko Fujimori was born in Lima, Peru to Alberto Fujimori and Susana Higuchi. In 1990, Alberto Fujimori won the presidency. In 1994, Higuchi was stripped of the title of First Lady, declaring that her husband had tortured her after she tried to denounce corruption. This led to her daughter, Keiko, assuming the First Lady position and denouncing her mother’s claims by calling her “unstable.”

In 1993, Keiko Fujimori started a Bachelor of Science in Business Administration at Stonybrook University, and the following year, she transferred to The University of Boston. However, not all was well: Peru’s Congress began investigating the sources of funding for Keiko Fujimori and her siblings’ education. According to the Peruvian General Comptroller, Keiko Fujimori and her siblings’ total cost of tuition and board was approximately USD 1.1 million. At the investigation commission established by Congress, Fujimori declared that the total cost was actually USD 460,000, claiming that her father acquired the money from selling a property for USD 660,000. It has since been confirmed that the property in question was only sold in 1998. In fact, Vladimiro Montesinos, former right-hand of Alberto Fujimori, testified that the tuition and board of the four Fujimori siblings were embezzled from public funds, particularly from the Military’s Intelligence Service budget.

At the turn of the millennium, Alberto Fujimori attempted to re-elect himself for a third term, despite the constitution setting a limit of only two consecutive presidential terms. In the same year, after several corruption scandals and massive protests, he fled to Japan. Five years later, in 2005, Fujimori Sr. travelled to Chile so that Peruvian President Alejandro Toledo could request his extradition; the government of Chile granted this request in 2007. Later on, Fujimori Sr. was found guilty of corruption and enabling a death squad known as Grupo Colina that carried out underground operations such as murders and forced disappearances of suspected terrorists and journalists. Fujimori was subsequently sentenced to 25 years in prison. According to Transparency International, Alberto Fujimori embezzled USD 600 million, making him the 7th most corrupt leader in the world.

In 2006, Keiko Fujimori was elected to Congress with the most votes in Peruvian history. When Fujimori was elected, she lived part-time in the United States to earn an MBA at Columbia University. Political opponents would later question her about missing 500 days of work in Congress while pursuing her education.

In 2010, Keiko founded Fuerza 2011, which she would later rename Fuerza Popular, and ran for president. She subsequently lost the election to Ollanta Humala by a margin of only 2.9% of all votes. In 2016, she lost another election to Pedro Pablo Kuczynski, this time, by a margin of 0.23% of the votes. Fujimori accepted the results but made some questionable remarks, calling the results “confusing” and claiming that votes from rural communities could change the results in her favour.

In the 2016 congressional election, Fuerza Popular won 73 of the 130 seats in Congress, earning an absolute majority. Once elected, the party proceeded to boycott any policies supported by the Kuczynski administration. For instance, Fuerza Popular opposed so-called “Gender Ideology,” a progressive and gender-based approach to the national school curriculum, which they claimed was an attempt to homosexualize children that would cause cancer and AIDS. 82% of Peruvians supported Gender Ideology. Later, the controversy over sexual education became even more polarized when Fuerza Popular helped dismiss corruption charges against judge César Hinostroza, who had been recorded negotiating a bribe to free a child rapist.

After several failed attempts by Fuerza Popular to remove Kuczynski from office, he resigned in 2018, and Vice President Martín Vizcarra became the new head of state. During Vizcarra’s administration, Fujimori’s party continued clashing with the executive branch over Vizcarra’s proposed anti-corruption legislation. In response, Vizcarra dissolved Congress and called an election. At the new congressional elections, Fujimori’s party only earned 15 seats.

In November 2020, the newly elected Congress, supported by members of Fuerza Popular, approved a motion to remove Vizcarra from office due to “moral incapacity”. Peru’s constitution establishes that Congress can remove a president if they are permanently physically or morally incapacitated. However, the interpretation of “morally incapacitated” is up for debate. According to Peruvian political analyst Javier Alban, this constitutional tool should only be used when an infraction is so blatant that it leaves no room for interpretation. This was not the case in Vizcarra’s removal.

The apparent misuse of the term “moral incapacity” caused outrage and led to massive protests. Manuel Merino, who became President after Vizcarra’s removal, quickly resigned and was replaced by Francisco Sagasti. In 2021, as expected, Fujimori was yet again a candidate in the presidential race. Since none of the candidates won more than 50% of the votes in the first round, Fujimori and Pedro Castillo became opponents in the runoff.

The runoff was one of the most polarizing elections in Peruvian history. Strong national anti-Fujimori sentiment can be summarized in a quote by Peruvian writer Martín Roldán: “[t]he greatest political party in Peru is Anti Fujimorismo.” On the other hand, Castillo’s party took on a Marxist-Leninist ideology, which awoke a fear of communism among Peruvians. During the campaign, Fujimori’s strategy was to blame Castillo for encouraging a class struggle, accuse members of his party of terrorism, and claim that under his administration, the government would seize private property. Although Fujimori’s claims were not entirely unfounded, they were also fed by racism and classism against Indigenous people. For instance, Fujimori claimed that the forced sterilization of Indigenous women during her father’s government was nothing but a family planning policy. Ultimately, she lost the election by a small margin of votes.

With a better understanding of Fujimori’s political background, we can discuss her personal relationship with justice. On March 11th, 2021, Peruvian prosecutor José Domingo Pérez presented an accusation against Fujimori for leading a criminal organization, money laundering over USD 2 million, obstructing justice, and providing false information for administrative processes. According to the prosecution, Fuerza Popular received over USD 15 million in clandestine contributions for Fujimori’s presidential campaigns.

The origin of the investigation brings us back to 2016, when Fujimori’s party organized events to raise money. According to reports presented by Fuerza Popular, they raised over 4 million Soles (USD 1 million), but the prosecution revealed that Fuerza Popular was only able to justify thirty per cent of these funds. As investigations went on, it became clear that the events were a facade to introduce funds donated by the Brazilian construction company Odebrecht, which has been the centre of several corruption scandals in Latin America for bribing high-profile politicians. Between 2018 and 2020, Fujimori has been imprisoned twice under the ruling of “preventive prison time,” which applies to individuals being investigated and considered a flight risk.

Keiko Fujimori is currently awaiting trial for money laundering and other charges. The prosecution has asked for thirty years and ten months of prison time, so it might be a while before we hear more about the most controversial of Peruvian political figures.

Featured image: Flyer that reads “Keiko: Your father tortured your mother and you did nothing. No to Keiko.”. Photo by The Advocacy Project. Licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Edited By Erika MacKenzie