#Metoo?: How Japanese Legislation and Society Are Failing Sexual Assault Victims

Author’s note: this article may contain coarse language related to sexual assault, harassment, and violence. Reader discretion is advised.

The collapse of the Empire of Japan in the aftermath of World War II significantly reshaped the country’s politics and society. Even with the abolition of its army, Japan rose to become one of the driving forces in global affairs and the international economy. It now holds the third largest nominal Gross Domestic Product (GDP) worldwide and one of the highest Human Development Index rankings (HDI) in Asia Pacific. Yet, this remarkable socio-economic development was not equitably felt by all citizens. Japanese women were still subjected to many societal hardships, such as an overall climate of sexism perpetuated by outdated legislation. Given the limited impact of the 2017 #MeToo movement in Japan — and the considerable backlash faced by journalist Shiori Itō after coming forward about her experience with sexual assault that same year — it is clear that institutionalized sexism is still deeply ingrained in Japanese society.

Outdated legislation and concepts

The prevalence of sexism in Japan is evident when looking at the overwhelming lack of comprehensive, up-to-date legislation on sexual harassment and assault. Rape and sexual assault legislation was first codified in 1907 and entailed relatively mild punishments of up to three years in prison, compared to a minimum of five years for robbery. The definition of rape in this law also proved to be extremely narrow, limiting sexual assault to forceful vaginal penetration, thereby excluding male victims.

Additionally, perpetrators could only face legal prosecution if the victim came forward and filed a formal complaint, an inherently demanding and mentally draining process for survivors. Furthermore, sexual abuse by parents and guardians against minors under the age of 18 was only considered a crime if “violence or intimidation” were involved, which is also notably hard to prove, especially when the victim of such abuse is a young child.

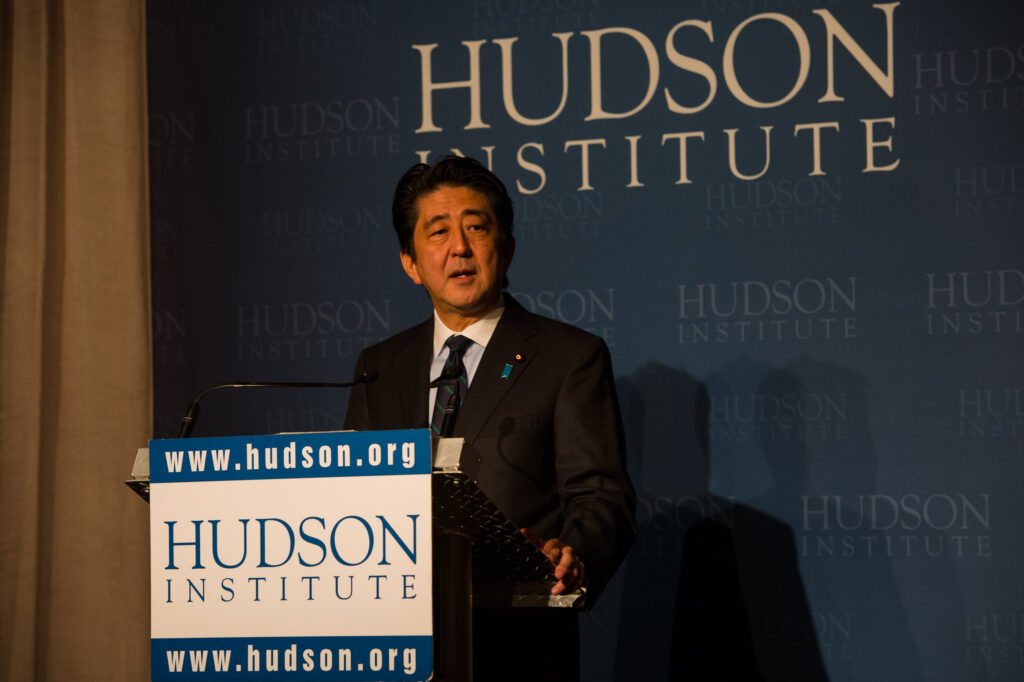

What is perhaps most striking about the history of sex crime legislation in Japan is that the 1907 rape law remained unaltered for over a century. The first — and only — amendment ever made to the law was proposed by the administration of incumbent Prime Minister Shinzō Abe in 2017 following extensive campaigning by activists promoting substantial changes in societal views of rape victims.

The main characteristic of this amendment was its inclusion of oral and anal rape in the definition of sexual assault. It also extended the minimum prison sentence to five years and revoked the requirement that victims must press charges to prosecute abusers. But, the amended law imposes two conditions for a judge to rule in favour of the victim. First, the victim must not have expressed consent at any point during the encounter, and second, there must be proof that the victim was unable to resist due to physical violence or threats. Still, failure to meet these conditions should not justify or exonerate acts of sexual assault.

For instance, in the spring of 2019, a string of acquittals in sexual assault cases sparked outrage in Japan. One of these cases involved a 19-year-old girl who was regularly molested by her father since the age of 15. While it was established that the intercourse was non-consensual, the victim could not prove that she was unable to resist her father’s advances, leading to his acquittal on all charges. Rulings like this overlook the now widely recognized experience of involuntary paralysis (or “freezing”) as a natural physiological and psychological response to sexual assault that renders victims unable to move or react in any way. The amended law still overwhelmingly places the burden of sexual assault, and the responsibility of proving that the act even occurred, on the victim. These legal shortcomings echo the Japanese #MeToo movement’s failure to initiate a meaningful dialogue on sexual violence in 2017.

#MeToo: a failed movement in Japan

The #MeToo movement was first introduced by activist and sexual harassment survivor Tarana Burke on MySpace in 2006. However, in October 2017, amid widespread sexual abuse allegations against Hollywood producer Harvey Weinstein, actress Alyssa Milano precipitated the massive “#MeToo” online campaign to denounce the extent to which women suffer from sexual harassment and assault in contemporary societies. This campaign quickly gained traction and led to worldwide demonstrations seeking to end sexual abuse, harassment, and sexism.

However, the movement in Japan failed to significantly empower women as it did in other industrialized countries. The rise of #MeToo in Japan is widely associated with journalist Shiori Itō, who came forward in May 2017 to share her experience with sexual assault after being raped by Noriyuki Yamaguchi in 2015 after he invited her out for dinner. Yamaguchi, a former Washington bureau chief for the Tokyo Broadcasting System and fellow journalist with close ties to Prime Minister Abe, quickly dismissed Itō’s allegations, calling her a “habitual liar” and blaming her for being intoxicated during the assault. While Itō eventually won a lawsuit in December 2019, as a Tokyo court awarded her 3.3 million yen ($30,000 USD) in compensation from Yamaguchi, her case remains an exception in the Japanese legal landscape.

For the most part, unlike many other industrialized nations that witnessed a noticeable #MeToo upheaval, mass mobilization in Japan was negligible. Throughout 2017 and most of 2018, there were virtually no protests held in Japan in solidarity with #MeToo and victims of sexual assault. However, later in 2018, protests shyly emerged in Tokyo, demanding action against sexual harassment. Civil unrest was bolstered by the resignation of top-ranking Finance Ministry official Junichi Fukuda after a female reporter accused him of repeated sexual harassment. Protests were mostly promoted via Twitter, providing survivors and activists with a platform to express their discontent vis-à-vis a predominantly conservative society that consistently fails victims of sexual assault. Nonetheless, the fact that these protests broke out considerably later than in other countries, and at a smaller scale, shows how much of Japanese society is still oblivious to the gravity of sexual violence.

A culture of shame and silence

Itō’s legal crusade against Yamaguchi triggered a wave of hate messages and death threats, belittling her traumatic experience and insulting her with slurs such as “slut” or “prostitute.” When commenting on societal backlash, Itō criticized the mainstream media for trying to dismantle her case by discussing the outfit she was wearing that day, as well as her being intoxicated. According to Itō, experiences like hers are the result of institutionalized sexism in Japanese society which actively silences victims and prevents them from coming forward with allegations.

Itō‘s claims are far from exaggerations. A 2017 survey conducted by the cabinet office of Japan’s central government showed that over 95 per cent of incidents involving sexual violence go unreported and that discussing rape is considered “embarrassing.” Many important figures, including Itō, blame a culture of shame in Japan that discourages women from coming forward and teaches them not to say “no” when confronted with sexual advances. Prominent female figures have also perpetuated this culture. In a 2018 video, Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) politician Mio Sugita and other female conservative leaders mocked and shamed Itō, blaming her for being intoxicated and implying that she was trying to sleep her way into a job.

The hostile environment faced by sexual assault survivors was captured in a 2017 poll by NHK, Japan’s national broadcaster. Among the respondents, 27 per cent believed that sharing a private drink signalled sexual consent, while 25 per cent considered getting into a car with another individual a sign of agreement. The LDP, Shinzō Abe’s party, is known for being conservative and pursuing statist policies that have restrained civil society growth throughout the 20th century, resulting in a lack of well-funded activist organizations in contemporary Japan. Nonetheless, the central role of civil activism in amending Japanese sexual abuse legislation is promising for the promotion of long-term, bottom-up societal change.

Coupled with a culture of shame and silence that is still very much alive in contemporary Japanese society, LDP policy has created an unsafe environment where coming forward with sexual assault allegations is frowned upon. However, Itō’s successful lawsuit, and the vital media coverage she brought to the issue, may be a sign of progress for victims of sexual violence in Japan. Most importantly, this story emphasizes the growing need to rethink legal practices that disproportionately burden survivors and the tendency to focus on the victim’s reputation and credibility instead of the abuser. While it is too early to say that mindsets are changing, the resignation of Junichi Fukuda and Shiori Itō’s success story undoubtedly set the stage for a heavy but necessary public debate.

Featured image “Go for it, Nadeshiko Japan!!! (頑張れ!なでしこジャパン。)” by Toshihiro Gamo is licensed under CC-BY-NC-ND-2.0.