Non-Secular: Church and State Relationship in Latin America

In 2016, Pope Francis chose Panama City to host the Catholic Church’s 2019 World Youth Day, a pilgrimage event that organizes millions of young people from around the world to participate. For the Catholic Church, Panama is a logical choice. According to the Latinobarometro, a polling institution focused on Latin America, Panama places the second most institutional trust in the Church of all Latin American countries, with 78% of Panamanians indicating trust in the Church. However, it has caused some controversy because of a perceived over-involvement of the supposedly secular government, and uncertainty in the leadership of the Catholic Church. Furthermore, the event is estimated to cost the government around 54 million USD, with a significant portion to be paid by tax revenue. Throughout social media, users have criticized the government’s financial investment in this Church-related event because several state affairs are left ignored. In particular, the lack of access to appropriate healthcare for millions of Panamanians, the discontinuation of certain scholarship programs for low-income students, and the lack of access to potable water for hundreds of communities, among other growing concerns.

This is not the first time the current president of Panama, Juan Carlos Varela, has been criticized for his tight relationship with the Catholic Church. He has frequently travelled to the Vatican as a head of state and has used state funds to aid the Church. The general negative reactions to the event though are not against the Church or even the event itself, but rather against the role of the State in this Church-related event. This intertwining of Church and State is ultimately seen as a challenge to the secularism of the State.

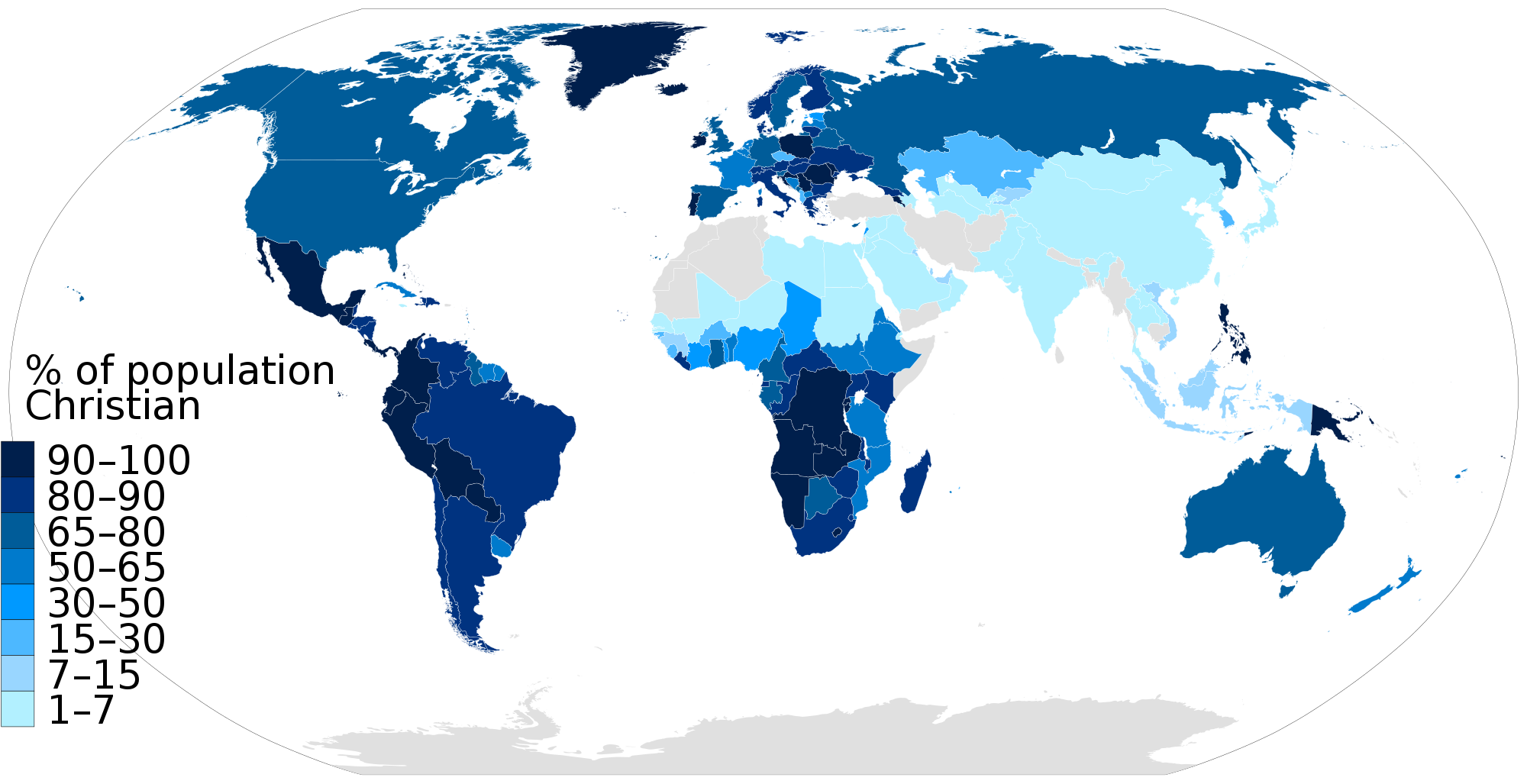

The Church has been a political institution in Latin America since the Spanish conquistadores arrived on the mainland. Despite the declining influence of the Church everywhere else in the world, in Latin America the Church still influences the state. According to the Latinobarometro, even though overall trust in the Church has declined to 63% in 2018, it is still more trusted than any other institutions, including the government, courts, and the police. While this figure is true of all Latin America, trust in Central America is the highest. This allows for the close involvement of the Church in the State and its legislative affairs since governments and aspiring candidates typically align their political beliefs with popular sentiment in order to get elected or re-elected into office. As a result, the Church continues to have an active political influence that is deeply influential in state policies. Due to its saliency in the political sphere, the faithful’s political stance in the region tends to be whatever is endorsed by the Church, further preventing a proper separation of Church and State. With 40% of Catholic believers residing in Latin America and the incredible amount of institutional trust placed in the Church, it is only natural that the path for popular and electoral support often involves alignment with Church beliefs.

Religious congregations and clergy especially have used their far-reaching influence on their congregations to channel key political information by directly endorsing or rejecting candidates, legislation, and/or social movements. Panama saw such influence in 2016 when Law 61, which proposed implementing a progressive sexual education system in public schools, was brought to the floor of the National Assembly. Soon after, the law was rejected in the Assembly after various Christian NGOs and the Church vehemently opposed its approval by organizing a country-wide march citing that the law was “impregnated with gender ideology”. TVN, a local news channel, interviewed various participants of the march who explained that while they had not read the document, they based their stance on what they had heard from their congregation. The law was eventually approved in 2017 after 20 modifications based on recommendations from evangelical groups which radically changed the core of the law. It now has extensive restrictions on sexual education: it actively prohibits the mention of birth control methods in school and promotes an abstinence-based approach.

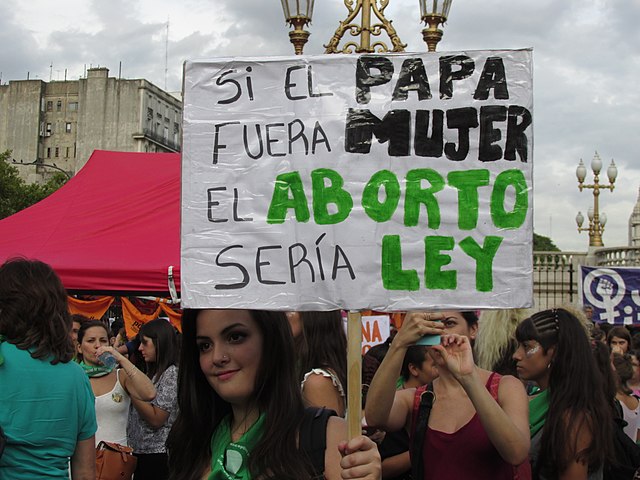

Abortion is another extremely contentious topic that confronts with the tension between Church and State. Latin America is one of the regions with the most extreme restrictions on abortions. Only six countries have made the practice broadly legal meaning that it is permitted either without restriction. In Panama, abortion is still illegal, except in cases of sexual violence or health risks, and punishable with up to three years in prison for the woman who has had the abortion, and up to six years for the physician performing the procedure. Other countries in the region have even harsher penalties: in El Salvador, Nicaragua, and Chile, abortion is prohibited in any circumstances and is punishable by up to 30 years in prison. The struggle of Latin American women to achieve the basic human right to control their own bodies can be rooted, once again, in the strong political influence of the Church on government affairs.

During Costa Rica’s presidential campaign. Evangelical pastor Ronny Chaves declared:

“We are at war, we are on the offensive. No longer on the defensive. The Church has long been stuck in a cave waiting to see what the enemy is doing, but today it is on the offensive, understanding that it is time to conquer territory, time to take up places in government, education and the economy.”

The current political stance of the Church is not a passive one any longer. Its far-reaching influence in Latin American policies seems to be growing even as numbers of their faithful are declining. Nevertheless, they are the number one lobbying interest group in the region whose influence is constantly threatening the secularism of the State. Ultimately, opponents to the World Youth Day in Panama do not oppose the Church, or even the event itself, but the involvement of a secular State in Church events. As one user expressed on Twitter, “I do not oppose the World Youth Day, I oppose using state-funds”. Another one responded to a State commercial by saying that “As a Christian Catholic and laic of the Church, I request that you cease to use the logo of [the World Youth Day] to promote government projects.” Thus, the problem is not with the Church or even its political stance, but in its unconstitutional hunger to continuously blur Church-State divisions to push its political agenda by threatening the secular nature of the State.