North Macedonia: The Implications and Process of Changing the Name

NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg and the Prime Minister of the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, Zoran Zaev.

NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg and the Prime Minister of the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, Zoran Zaev.

For nearly thirty years the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia (called the FYROM officially at the UN and the Republic of Macedonia informally) was in dispute with Greece over the name the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia. Macedonia and Greece’s parliaments have voted to start the process of renaming the country “Republic of North Macedonia” in accordance with the Prespa Agreement, which is a major step towards ending a decades-long stalemate with Greece and opening a door to Macedonia’s entry to NATO and the EU.

The path to this name change has not been easy. The two regions, “Central Macedonia” and “Eastern Macedonia and Thrace” in the north of Greece and the FYROM both claim the title of “Macedonian” and the identity politics have affected relations between the two states for the past 27 years. Greece argues that “Macedonia” implies territorial claims to a Greek province of the same name in the north of the country. There is a further issue of national and ethnic heritage which underlies the territorial dispute over which nation can claim the ancient Macedonian kingdom which was the birthplace of Alexander the Great. Furthermore, the name that Macedonia holds in the international sphere is also problematic. When the country secured their independence from Yugoslavia in 1991, it refused “to be associated in any way with the present connotation of the term ‘Yugoslavia’,” as this would open their borders to possible territorial claims from Serbia as well as Greece.

In June, the naming dispute was finally resolved by negotiations under a new pro-western government in Macedonia and compromises made by both FYROM and Greece. Macedonia elected a new pro-western government in 2017 which reopened negotiations so the new government could move forward with their political agenda of westernizing the country. Since both countries were motivated to reach a solution, they found compromises on some of the big demands, particularly the issue of whether “Macedonia” could be in the name of the new country. By adopting the geographical identification of Macedonia as “North Macedonia”, they were able to reach an agreement.

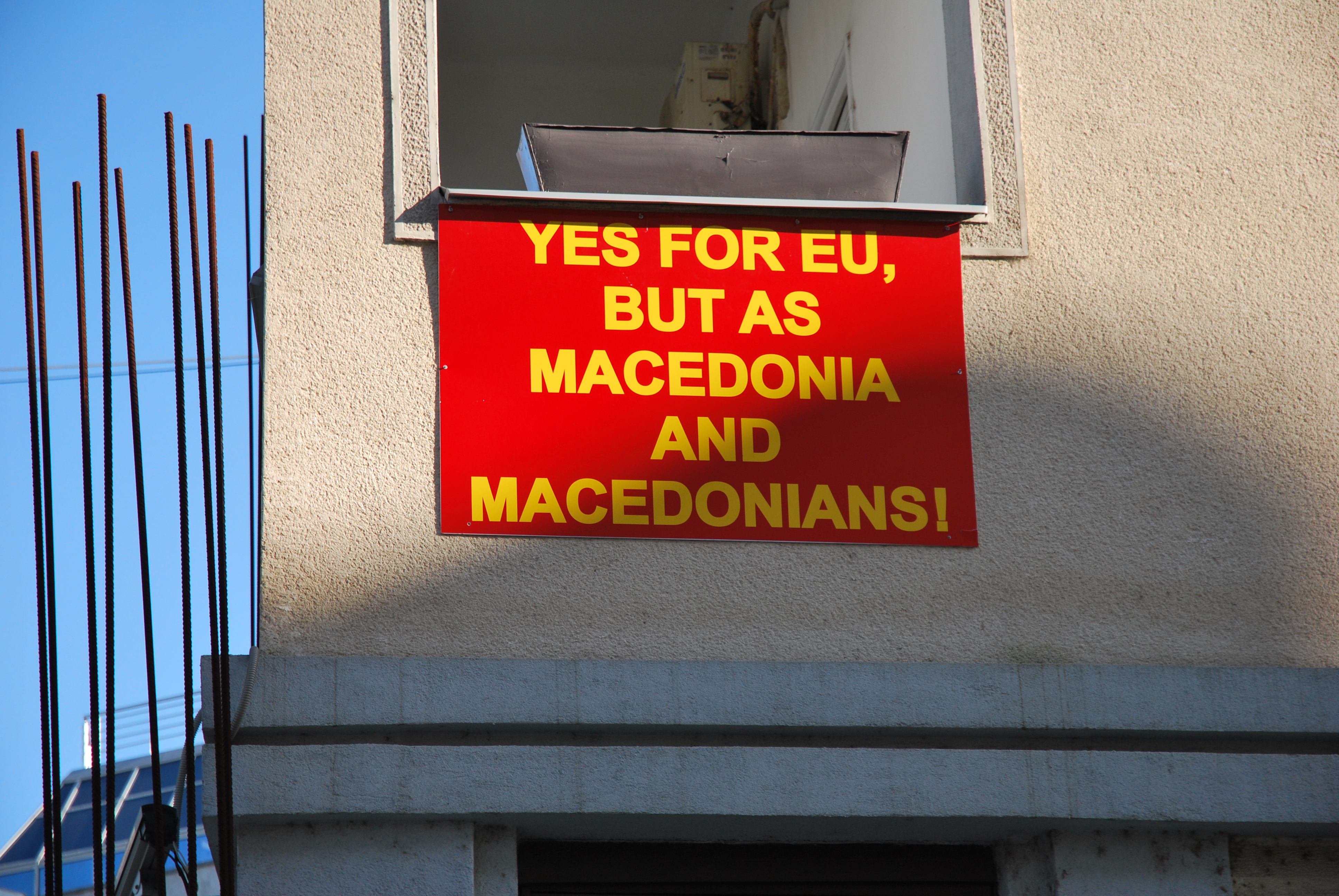

The Prime Ministers of Macedonia and Greece made headway in discussions regarding the naming issue in June of 2018. This led to a referendum put to the public to decide whether or not they would change the name of Macedonia. The majority party has encouraged citizens to vote “yes” on the question: “do you support EU and NATO membership by accepting the agreement between Macedonia and Greece?” The fact that the name of the new country has been left off the ballot demonstrates just how contentious the name change is among these people. For some citizens of Macedonia, adding “North” to the name of their country is a threat to their national identity, even though the agreement with the Greeks allows the adjective “Macedonian” to be used to describe its citizens and language. Most of the Greek public is still against the name “Macedonia” being used at all and there are still huge demonstrations happening across Greece in protest.

However, the opinion of the voting demographic in Macedonia leading up to the historic referendum was divided. The opposition party in Macedonia called for a boycott which affected voter participation. In order for the vote to be valid, there was a required 50% turnout. Among those who voted, only 35% cast their ballots, but over 90% of the votes were in favour of changing the name and taking the deal with Greece.

Although the Prime Minister of the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, Zoran Zaev, failed to secure the required voter turnout to validate the decision, he went forward with bringing the plebiscite to the Skopje parliament. Of the 120 seats in parliament, 80 voted in favour of renaming the Balkan country to the Republic of North Macedonia. This secured the two-thirds majority needed to enact constitutional changes. Macedonian Members of Parliament who were in the ruling VMRO party who abstained or did not vote in favour of the change were immediately expelled from the party after the parliamentary vote. The eight opposition MPs who voted in favour of the change were accused of being bribed into changing their vote. Regardless of the circumstances of the decision-making process regarding the name change, it appears that the first step has been passed. There need to be two more amendments which require a simple majority to pass, which seems possible now after the 2/3 majority result in parliament. Furthermore, each change needs to be done within a 30-day window. Once Macedonia formally changes the constitution, the Greek parliament will also go through a similar process in order to complete its part of the agreement. This must be done after the Macedonian Prime Minister Zoran Zaev has already completed the process with “North Macedonia”. This timing could make it very tricky, since Tsipras’ party is perhaps the only party in the Greek government that supports the name change. If the changes are not made and established before the 2019 elections, there is a chance of everything being for naught, especially if an opposition government takes power.

Among the key issues of heritage and territory, which lie at the heart of the dispute, are the international dimensions of the issue. Since the 1990s, Greece has blocked Macedonia’s attempts to join the United Nations and in 1994, an economic embargo was imposed on the Balkan state as a result of the dispute. In 2008, Greece vetoed Macedonia when it attempted to become a member of NATO. One year later, Greece similarly blocked their E.U. membership bid.

Russia and the United States also stand in opposition regarding the matter and have “traded allegations of interfering in Macedonia’s affairs”. Russia opposes Macedonia’s aspirations to join NATO, while the U.S. supports them. Russia continues to oppose any expansion of the NATO alliance, especially from any country directly bordering Russia. The United States throwing their support in favour of the name-change exemplified the western backing for strategic membership of NATO and the EU for Balkan countries. The United States accused Moscow of running a disinformation campaign to turn Macedonians against the referendum. In response, the Russian Foreign Ministry stated that the U.S. and E.U.’s interference in Skopje’s internal affairs “has already surpassed conceivable boundaries”. The stakes in re-naming Macedonia are high because reaching an agreement with Greece over the country’s name brings Macedonia one step closer to joining NATO and the EU. This orients Macedonia further towards the west and distances the country from Russia.

Until recently, Macedonia’s insistence to maintain their name has stopped the state from improving relations with other nations, and this resulted in harmful effects to their economy by blocking Macedonia from joining special economic zones that facilitate free-trade and export-oriented industrialization. As of November 1st, 2018, flights have resumed from Athens to Skopje after a twelve-year blockade. However, beyond the increased accessibility of transportation between the two countries, there are also the added elements of Macedonia’s new international possibilities. Macedonia will be able to attempt to join the E.U. and NATO and focus more on its economic development since Greece will no longer be fighting the country’s every move.

Edited by Helena Martin and Artemis Archimandriti