Olympic Host City Hangover: Looming Legacies of Rio 2016 and Tokyo 2020

Tokyo, Rio de Janeiro, Montreal, Los Angeles. All four are among a select few metropolises that share a common legacy of hosting the Olympic Games. Recollections of the games tend to invoke feelings of pride and patriotism, stemming from sensationalized victories and sporting firsts, like the shared Qatari and Italian high jump gold at Tokyo 2020. Looming before, during, and after every Olympics, however, is the less glamorous host city hangover: when cities awarded the coveted hosting gig inevitably experience escalating social and economic costs to accommodate the needs of elite-sport enthusiasts. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, and Tokyo, Japan, have been the most recent and well-documented victims of an elusive Olympic prestige.

Debts from hosting begin to incur well before the games commence. On average, hosting bid submissions to the International Olympic Committee (IOC) begin eleven years before the actual games. Such early preparations, in addition to expenditures on infrastructure and tourism projects, create short-term benefits like job creation and increased tourism. However, these benefits are quickly overshadowed by long-term debt crises that can cripple city economies, exemplified by the forty years it took Montreal to repay its debt from the 1976 games.

While Olympic revenue is diversely sourced from television, domestic sponsorships, ticket sales, and licensing agreements, initial budgets have consistently and grossly underestimated final and ancillary costs like environmental clean-up. Moreover, as the IOC secures much of this revenue from international sponsorships and broadcast media rights, corporations and foreign investors reap the benefits of increased media visibility. Taxpayers, meanwhile, bear the brunt of the debt by enduring taxes on products like tobacco, hotels, and property. Corporatization cleverly integrates these costs into products and services that will inevitably be consumed. Considering that hosts typically go over budget, taxpayer costs range from $2,000 and $11,000 per household, with taxpayers often oblivious about how their taxes are allocated and materialized. It is estimated that less than two percent of the Olympic budget now stems from private-sector funding. Taxpayers then face the double burden of disproportionately bearing hosting costs and seeing their needs deprioritized.

An unsuccessful bid for hosting the 2016 Olympics cost Tokyo an estimated USD 150 million, which had jarring microeconomic implications for the city of Tokyo. For economically developing countries like Brazil, hosting has been even more financially cumbersome. Following Rio 2016, a state of “public calamity in financial administration” was declared. Furthermore, amidst mounting pressures of being the first South American country to host the games, policing costs required a USD 900 million bailout from the Brazilian federal government just 36 days before the games’ commencement. Allegations of fraud and illegal payments have complicated the financial compromises made to amass the prestige of hosting the games.

Environmental degradation has likewise been a major area of contestation between Olympics critics. Some view the mammoth resource allocation to elite sporting events as better dedicated elsewhere. In contrast, others argue that eco-friendly initiatives at Tokyo 2020, like medals from recycled electronic waste and cardboard beds, have ushered in a new era of sustainable architecture. However, constructing new venues quadrennially for an event that lasts two weeks accumulates environmental costs, making welcome gambles with sustainable sporting short-sighted at best. Moreover, architects have co-opted the Olympics as a creative outlet for architectural prowess, making sustainable endeavours more of an homage to artisanship than the environment. Logistical arrangements and practices for Tokyo 2020 have been marketed as environmentally friendly more than they have tangibly minimized environmental impact. This suggests greenwashing is at play and can be attributed to the considerable influence of private and corporate actors lobbying for, financing, and sponsoring the games. Motivated first and foremost by profit maximization, private actors strategically aim to situate their environmental consciousness within an event whose benefits are becoming harder to vouch for.

In the context of environmental degradation, geographic vulnerability to climate change only exacerbates existing socio-economic repercussions. In Japan, rising sea levels, frequent typhoons, and the aftereffects of 2011’s Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster have threatened Japanese livelihoods and undergirded economic struggles. The Japanese government has responded to these criticisms by promoting Tokyo 2020 as the “recovery games,” showcasing Japan’s progress since these pivotal events. Yet, ‘recovery’ has been characterized by the relegation of more economically vulnerable people like the homeless away from tourism hotspots and toward the suburbs. Tokyo’s pursuit of infrastructural developments at the cost of its disadvantaged populations has consequently evidenced gentrification as an “intentional byproduct” of hosting the games.

The “recovery games” narrative has also been used to excuse the additional USD 2.8 billion cost to postpone the games due to COVID-19 . This is amidst a ban on spectators for public health concerns which has plummeted income flows from tourism by around USD 800 million and supplemented pressures on economic recovery. Again, critics view these additional expenditures as better allocated to vaccine purchases and facilities like hospital beds for COVID-19 patients.

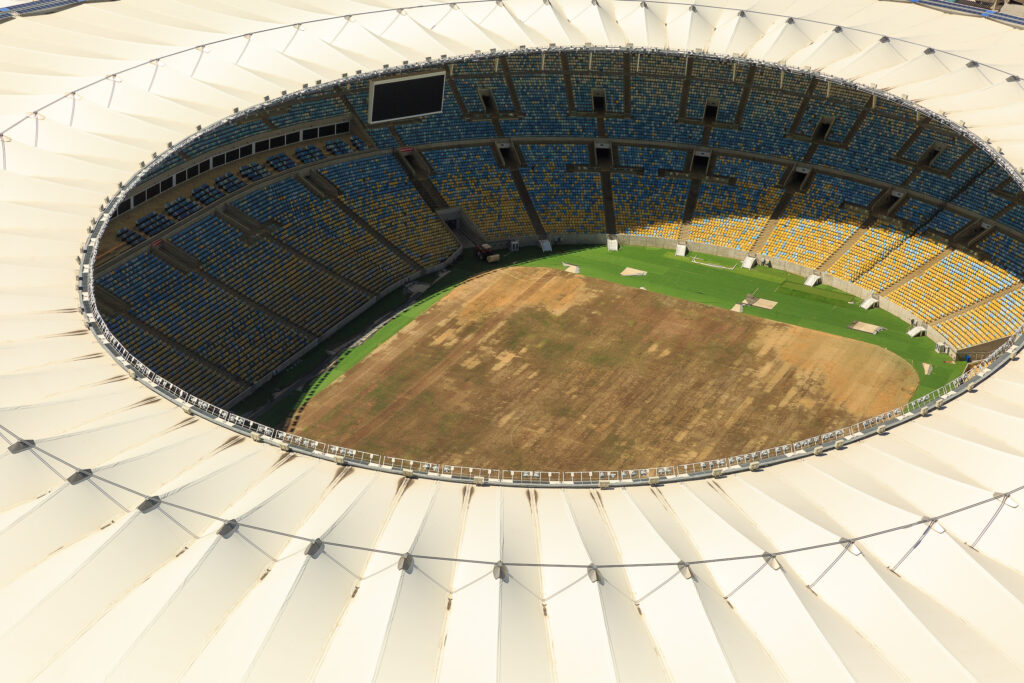

Brazil has come under similar scrutiny for prioritizing the building of transportation and housing facilities for Rio 2016 despite the pollution in Guanabara Bay posing a significant environmental and health hazard. The then ravaging Zika virus and the super bacteria Klebsiella also brought attention to wastewater and sewage treatment, whose quality improvement has remained an empty promise from the Brazilian government. Even more striking is that these pollutants leached into waterways used for Olympic sports like rowing and swimming, posing serious health risks to athletes. To defend governmental efforts to host the games, Rio’s Mayor Eduardo Paes alarmingly affirmed “no problems” health-wise, despite several independent microbial tests contesting otherwise. Still, these environmental and health risks have been secondary to the allure of investing in facilities rendered futile or minimally useful shortly after the games end.

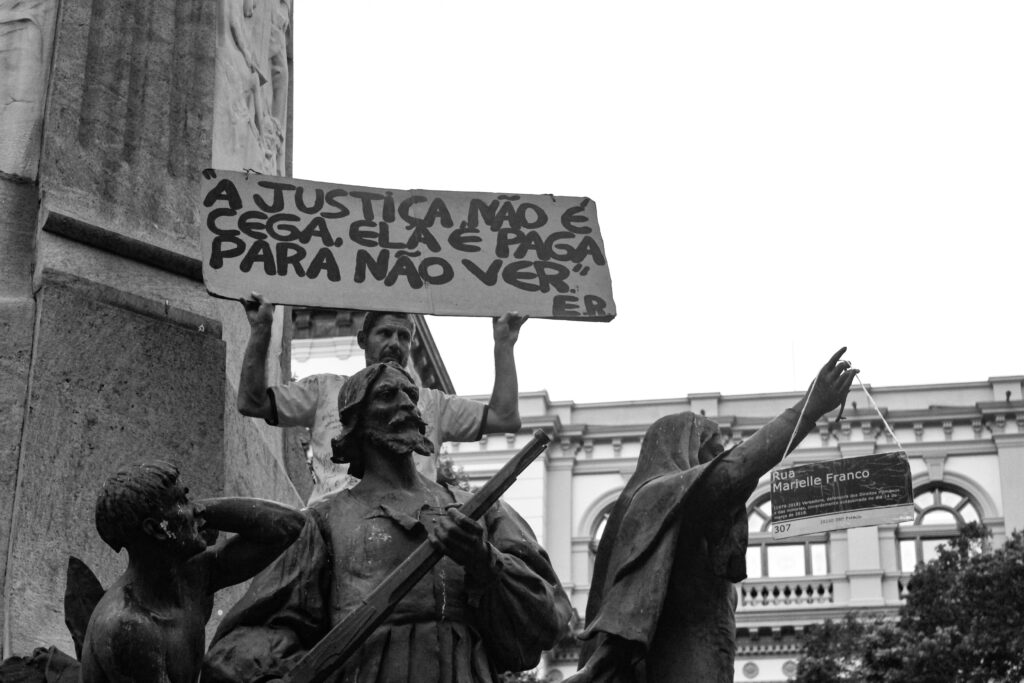

In the urban shantytowns prevalent throughout Rio, infrastructural endeavours authorized by Paes forcibly evicted poverty-stricken tenants from 14 favelas. All this to make way for access roads and parking lots for an athlete village that now resembles a ghost town. Gentrification has created “a crisis on top of a crisis,” with soaring inequality manifesting in record-breaking crime rates, deep recession, and delayed payments of pensions and salaries to teachers and hospital workers.

The trend of prioritizing visitors’ needs over those of locals is a trend observable in many Olympic host cities. Yet, hosting bids remain in demand due to validating a host city’s potential, despite knowing of and paying for the exorbitant costs that make the glory of hosting elusive. Cities like Toronto have openly declared the unaffordability of a 2024 bid, but Rio and Tokyo remained captivated by the illusion of Olympic prosperity.

The IOC’s revamped Olympic Agenda 2020 has induced some welcome changes, including lower bidding costs, using existing facilities, and implementing sustainability initiatives. While Tokyo 2020 has been a step in the right direction, so long as new cities rudimentarily build facilities rather than use existing infrastructure, the “hazard of shiny new hosts” is inevitable. As the persisting socio-economic realities of Rio and Tokyo demonstrate, surmounting social, environmental, and financial reparations mean hosting costs outweigh benefits, which, in turn, menaces repeated host city hangovers.

Featured image: “Olympic games stairs of the year” by Kirill Sobolev is licensed under Pixabay License.”

Edited by Chino Ramirez