Once Power, Now Peril? The Legacy of Protests in Iran

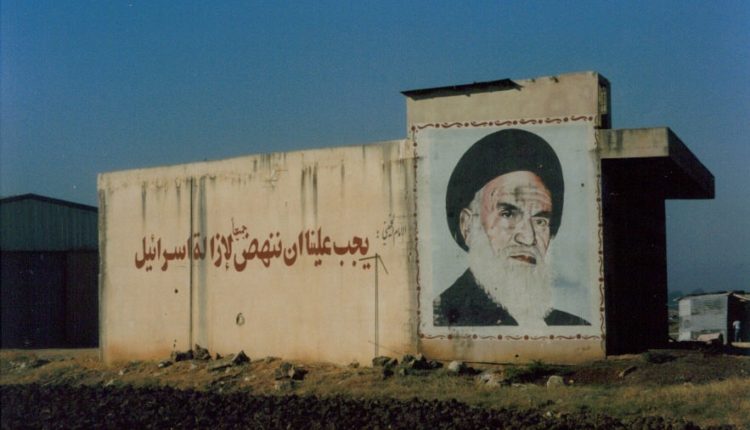

The anniversary of the Iranian Revolution which is commemorated annually on February 11th. On the poster is Ayatollah Khomeini and his successor, Ayatollah Khamenei.

The anniversary of the Iranian Revolution which is commemorated annually on February 11th. On the poster is Ayatollah Khomeini and his successor, Ayatollah Khamenei.

After the killing of Qasim Soleimani and downing of Ukranian Flight 752 last month, protests erupted within Iran in outrage against the United States, then against the Iranian government. Meanwhile, the country’s diaspora anxiously anticipated the future of the Islamic Republic of Iran. Some revel in the idea of the Shiite fundamentalist Iranian regime coming to its end. The Islamic Republic is often cast as “backwards” because it abandoned the Pahlavis’ economic liberalization and veneer of multiplicity in exchange for theocracy just over four decades ago. The previous government was marked by vast social change and is generally remembered as significantly more tolerant toward religious minorities within the country. However, while the Pahlavis brought religious recognition and inclusion to some, they failed to extend this tolerance to the Shi’a majority and enacted widespread political repression. The Shah’s stride toward a developed Iran is remembered by many as a period of economic and social disenfranchisement for particular groups. The marginalization the Shi’a population experienced during the Pahlavi reign served as the fuel in the effort to make Islamic ideology the ruling doctrine and put Ayatollah Khomeini into power. While it may be difficult for outsiders to understand how the selectively liberal Pahlavi dynasty gave way to a deeply conservative and theocratic contemporary Iran, it was this bubbling public resentment that caused regime change.

Prior to Pahlavi rule, Iran had religious governance as its early Qajar and Safavid leaders emerged as the champions of Shia Islam. Shiism became synonymous with Qajar Persia in the context of colonization and capitulation across the Middle East. Shiism was the basis of which Qajar rule was legitimized as rulers used rhetoric like “protectors of Shi’a Islam” to justify their power and suppress the multiplicity of Persia’s religious inhabitants.

Living in Reza Shah’s Iran was a clear improvement for some religious minority groups. For example, Jews were legally excluded from society in previous periods, but Reza Shah banned forced conversions and the idea of uncleanliness of non-Muslims that had appeared under previous rulers. Under Pahlavi rule, Persian Jewish welfare improved, and they were made equal citizens under the rule of law—a reality the modern populations had yet to experience.

Recognizing minority religious rights was a pragmatic decision for the Pahlavis. Reza Shah sought to build a global powerhouse in Iran and used Persian ethnonationalism to unite the populace instead of the religious legitimacy of his predecessors. Within the bundle of Pahlavi reforms, catalyzed by Reza Shah’s successor Mohammed Reza’s “White Revolution,” came a sale of some nationalized industries; the development of rail, air, and road networks; the enfranchisement of women; and the vast expansion of literacy to rural areas. The White Revolution of 1960-1963 aggressively modernized and industrialized the Iranian state, placing it on a new pathway of development.

Because the poorest third of Jews who predominantly lived in the provinces mostly moved to Israel prior to the White Revolution, those who remained lived in higher numbers in non-agrarian economies; these reforms were especially beneficial to them. The Jewish community was scapegoated by the discontented Shi’a masses who felt politically and economically excluded in the Shah’s new model of multiculturalism and capitalism. Iranian Jews were living their ‘Golden Age’ and flourished proportionate to their population size. The community at large was highly represented in the country’s universities, medical staff, and in other highly regarded professions. However, as economic disparity continued to plunge much of society into financial hardship, discontent with the Shah and his beneficiaries rose.

The Shi’a majority experienced a diminishment in their power as a result of said reform, and their religious leaders were losing their voice in government amid the Shah’s effort to secularize. These clerics expressed opposition towards the Shah’s reforms as the array of liberalization efforts chipped away at their power, including that over legal and education systems. Meanwhile, the Iranian masses blamed their grievances on economic misfortune and increasingly limited political participation. The Shah developed a secret police force called SAVAK to censor, jail, torture, and execute dissidents. A number of political parties were banned, and torture and harassment of the general Iranian population became common practice. Compounded by the hindering of the economy and a decreasing means for political expression, the Iranian masses looked to radical, yet influential figures for means of change.

Khomeini’s Rise to Power

Discontent with the Shah was so widespread that secular intellectuals provided Ayatollah Khomeini with the platform to emerge as a religious leader. These intellectuals had transformed their goals from reducing the power of the Shi’i Ulamas, to using these figures as allies to depose the Shah. The suffering rural poor was disenchanted by the Shah’s modern Iran and joined the intellectuals, Marxist parties, and religious scholars in an effort to reform their government from the ground up. Support for Khomeini’s utopian Shiite theocracy increased as cyclical violence ensued in January of 1978. Demonstrators took to the streets opposing the Shah and his domestic and foreign policy. He responded by sanctioning violence against protestors. Instead of suppressing these voices, each death fuelled further protests. The movement, enthralling those from the secular left to the religious right, was cloaked in Shi’i Islam, mourning the death of Iran’s once traditional, conservative, and feudal orientation.

The Shah was overthrown in February of 1979 and sought asylum from his American ally. With Khomeini in power, Iran became the ‘Islamic Republic of Iran’ shortly thereafter. In a 1979 referendum voting on the potential of an Islamic Republic, Iran’s 99% Muslim population voted almost unanimously in favour. People likely used Khomeini as a vehicle in which to assert their dissatisfaction with the Shah, his policies, and his foreign allies such as Israel and the US. Iranian revolutionaries were successful in restructuring their government to mirror its Qajar and Safavid bases and characteristics, using Islam as a blueprint for future domestic operations. This 1979 referendum is often used by the Iranian regime to justify their democratic foundation, while also serving as the initial fusion of political and religious life.

The distinction between the perception of Islam as oppressive in and of itself and the regime merely using a revivalist interpretation of Islam to justify their oppressive tactics is an important one. The ways in which Iran changed as a result of new reforms and alliances implemented during the Pahlavi Dynasty served as the foundation of the construction of today’s regime.

The Pahlavi’s have a complicated legacy. They greatly benefitted some minority groups who had suffered economic deprivation on religious grounds, yet in turn isolated the Shi’a majority. It was this discontent with the dynasty that gave rise to the current regime. The Shi’a majority called for the transformation of their government by voicing their frustration with the Shah’s growing undemocratic practices, and favouritism towards the urban class. The current regime would do well to remember that ignoring the needs of the citizens in favour of ideological cohesion is not sustainable. In the context of government-sanctioned violence and economic turmoil—a remarkable continuity of the circumstances in which the Shah was deposed—the Islamic Republic of Iran may come to face a similar reality. Changes in government structure grow out of discontented masses, and the Islamic Republic may prove to be no exception.

Featured image by Mostafameraji on Wikimedia Commons, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0