Op-Ed: Unplaceable Creepiness, Gendered Unprofessionalism, and Uncle Joe

Last week, I attended a conference devoted to progressive causes. While there were many downright inspiring speakers, the conversations that I’m most likely to remember were those initiated by “Robert”, a retired professor who repeatedly invaded my personal space and rudely badgered me.

The incursions were subtle, occurring within the gray zone between friendly and inappropriate. It is difficult to pinpoint what exactly felt so invasive and annoying. I can’t quite find fault until I reverse the roles.

Would I, a small, young, and remarkably unthreatening woman, have ever reached onto a sitting person’s lap to pick up their name badge instead of asking the person their name?

Risen from my table to lean over another and grab a near-stranger’s arm to make an unimportant remark?

Repeatedly issued lunch and dinner invitations to young women who declined with increasingly emphatic assertions of clearly made-up excuses ?

Changed tables during a keynote speech and gotten in a person’s face to ask for contact information?

Absolutely not.

This kind of behaviour is an especially insidious threat to women’s confidence in the public space partially because of a lack of language to describe it or ways to handle it. If sexual harassment is “unwelcome sexual advances, requests for sexual favors, and other verbal or physical conduct of a sexual nature”, then this was not harassment. There was no Harvey Weinstein waving a dick in my face. No Matt Lauer with his door-locking button. No mention of sex or anything else patently inappropriate. I did not protest the first dinner invitation or the first time he went out of his way to speak to me, because to do so would have been genuinely rude.

Still, he made me uncomfortable through interactions which I cannot imagine initiating with another stranger. He then depended upon my instinct to respond politely and upon his own plausible deniability of bad intention for his cover. What would I say to the conference organizers if I had decided to report him?

Would I have said: “Excuse me, this man grabbed my name tag off my lap, asked me to dinner and touched my shoulder”?

I have seen the dismissal that harassment complaints often meet, and I failed to convince myself that conduct this commonplace warranted official action. The only assertion about his gendered unprofessionalism that I can make with confidence is that he would not have treated me this way if I were a man.

The decision of what to do—report, walk away, make a scene, or politely excuse myself—is fraught. Arguably, responding tersely and excusing myself would have minimized time and attention spent on the uncomfortable encounters with “Robert”. And yet here I am, spending my time angry at him. Becoming upset over offenses that are so small and commonplace affords this old man more power over me than I would prefer. Instead of writing about the contents of the speech he interrupted, I’m writing about my discomfort with the liberty he took in our interactions.

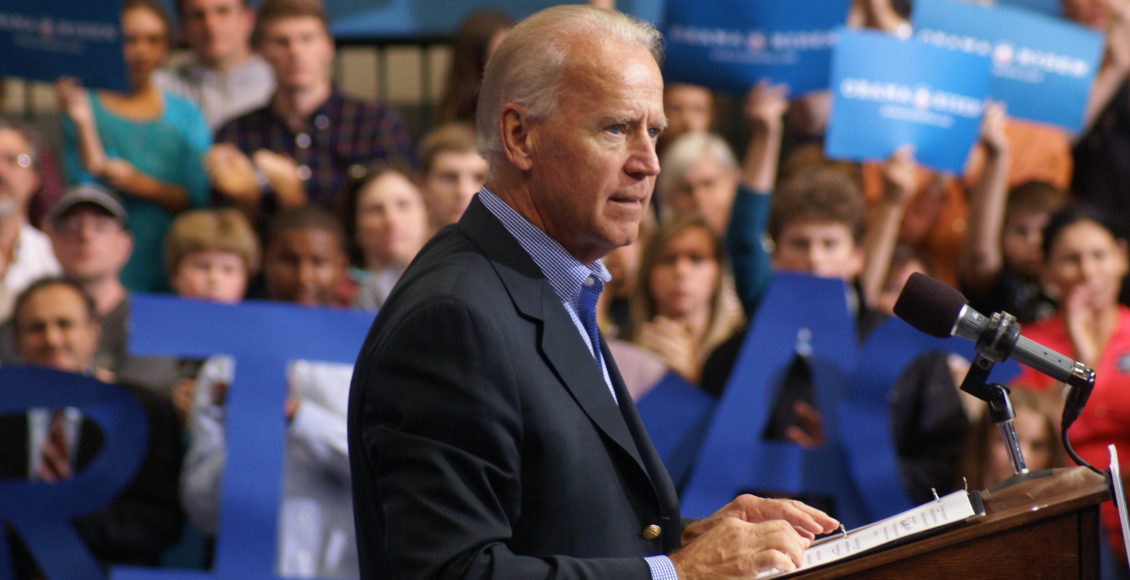

I’m sure that Lucy Flores must feel somewhat the same way. Instead of remembering or writing about the important speech she gave, she is gaining attention for her recollection of Joe Biden’s gendered unprofessionalism. Time and again, women’s own professional time and attentions are consumed by men’s refusal to use a standard set of professional etiquette or consider others’ perceptions of their actions.

Rationalizations of Joe Biden and men like him range from the “wasn’t that bad” logic that trivialises the victim’s experience to the denial that comes with a good character defense. Some afford these men the naiveté and aloofness that is allowed to casually sexist grandparents everywhere. Sure, it may be a waste of everyone’s time to get the oldest among us to renounce their Thanksgiving-table sexism. But is that really an indulgence that we should extend to a presidential candidate?

For anyone defending “Uncle Joe”: Why? Are Democrats really so confident that we couldn’t make one of the other 17-odd candidates work that we are willing to degrade our standards for someone whose etiquette requires such basic apology?

Biden’s latest statements on the allegations of inappropriate touching are “not once- never- did I believe I acted inappropriately” and “I may not recall these moments the same way, and I may be surprised at what I hear”. I’m sure that he believes he didn’t act inappropriately, and I’m sure that he does remember them differently, just as the man who badgered me for two days straight would likely claim incredulity at my discomfort. However, Biden’s judgment on the “appropriateness” of his actions is moot in comparison to the perspective of the woman whose hair he allegedly kissed. Validating Biden’s perspective is to prioritize an older, powerful, male perception of interactions over the experiences of the women usually subject to them.

Democratic support for Biden’s run will further invalidate this experience of rudeness and creepiness that many women share. In order to make women feel valued in the professional sphere, we have to make men accountable to the most basic principle of etiquette: try not to make people uncomfortable. We should demand that old men extend the same courtesies to young women that they do to their peers. We can do this by refusing to sanction gendered unprofessionalism in progressive presidential candidates. After all, the Roberts and Joes of the world will never see their behaviour as “inappropriate”. The responsibility to call this unacceptably gendered unprofessionalism what it is now falls to the Democratic party. Abdication of this duty will tacitly encourage young women like myself to continue politely excusing ourselves by making up meetings. If allegations of gendered unprofessionalism from multiple powerful women cannot retire an arguably disposable 76-year old, then how will I and future women ever be free from the “Roberts” of the world?

Edited by Christopher Ciafro and Alexandra Yiannoutsos