Opinion | Slavery Distorts Conservative Interpretations of the Second Amendment

Slavery's cultural legacy is expressed in fundamentalist interpretations of the Second Amendment.

This is the second in a two-part series on the origin of the United States’ Constitution’s 2nd Amendment. For the first part, click here.

Every mass shooting in the United States sparks a conflagration of debates over gun rights and the Second Amendment. Each time, Second Amendment fundamentalists crusade against anti-gun violence activists, marching against regulations that they perceive as unjust limitations on their constitutional right to bear arms. Yet if Second Amendment fundamentalists understood that slavery — and the white supremacy used to justify it — were the root impulses behind their aversion to regulation, perhaps they would be compelled to recognize their flawed legal logic.

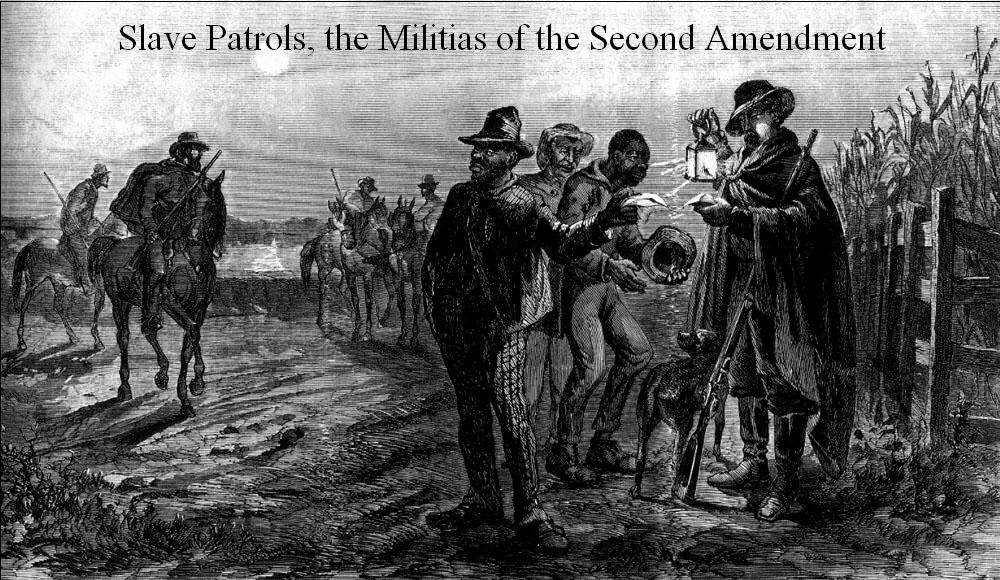

The institution of slavery likely determined the language of the amendment, passed in 1791. At that time, state militias were the primary agent of slave suppression. Because the original Constitution undermined states’ control of their militias, it potentially jeopardized the slave system. With the introduction of the Bill of Rights, the Second Amendment balanced state and federal control of state militias, securing slavery. However, far from ceasing to influence gun rights legislation, slavery’s legacy has distorted modern interpretations of the amendment: the historical context produced the wording itself, but the imprints that slavery left on the American cultural fabric gave rise to modern fundamentalist interpretations.

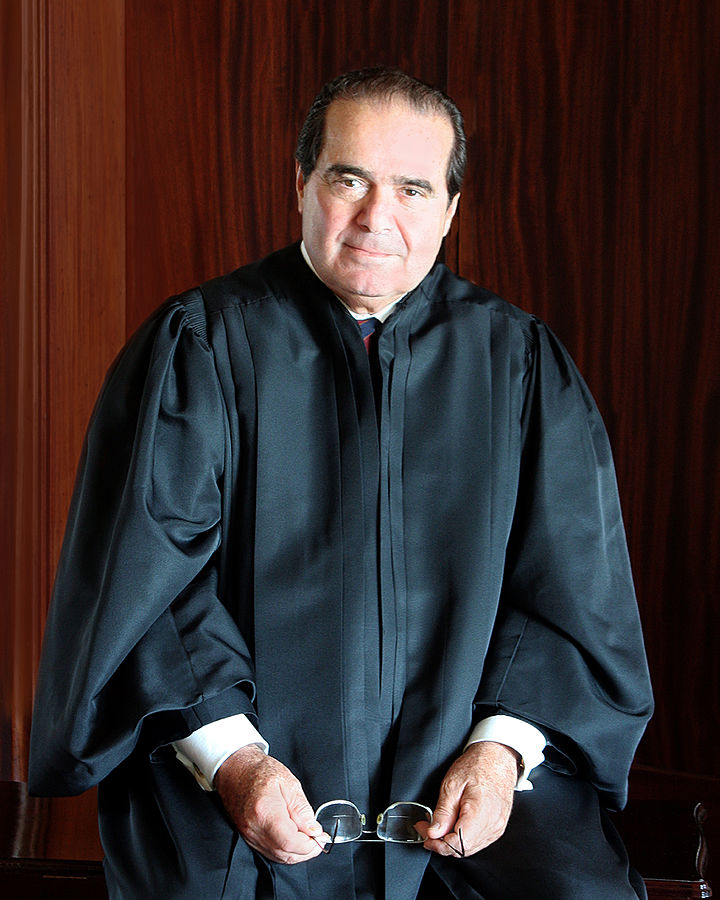

One of the most important of these interpretations was canonized by the Supreme Court in its 2008 decision in District of Columbia v. Heller. In Justice Scalia’s majority opinion, he reasoned that the Second Amendment could be divided into one “non-operative” clause followed by three “operative” clauses. In short, he said that the first clause relating to a “well regulated militia” should have no bearing on the scope of the right to bear arms, ignoring the historical context.

Dismissing the significance of the militia clause opened the door for broader legal interpretations. Scalia’s opinion was also the first to give official credence to the notion that the amendment was included as a ward against tyranny. This has impeded regulation efforts, because it has become an asset to conservative legal arguments, allowing conservatives to disdain as a heretic anyone who suggests repealing the amendment.

It seems Scalia, an avowed “originalist,” decided to throw reverence for the Founders’ “original intent,” along with basic grammar rules, into the dustbin of irrelevance. By modern grammatical logic, the first clause would be an absolute clause, modifying the whole sentence. Of course, in 1788, commas were not always used to enforce grammatical rules but rather to indicate pauses for speaking. Still, even without the commas, the logic is the same: the Founders were educated in the classical tradition, and they would have recognized the first clause as an absolute ablative rhetorical device — a grammatical structure in which the first few words dictate the meaning of the whole sentence. An honest consideration of grammar, then and now, renders Scalia’s conclusion bogus.

Even more damning is the fact that Thomas Jefferson, the author of the Declaration of Independence, was appalled by the misleading punctuation in the Second Amendment, and tried to rewrite it with one comma:

But Jefferson was too late: drafts of the Bill of Rights had already been sent to all of the state conventions, and sending a revision could have led to disastrous political drama. So the flawed version was adopted, obfuscating its meaning, and allowing lawmakers to make the seemingly reasonable argument that the clauses are independently significant.

Where does slavery come in? Scalia’s specious grammatical assumptions were born of political bias: the conservative fetishism for guns and unabridged Second Amendment rights formed the ideological wind that precipitated Scalia’s decision and those of other conservative judges.

That wind originally hails from the Antebellum South. Violence against slaves was the buttress of the slave system. Not only was this economically necessary, it was psychologically imperative to sustain the system. Moreover, the ever present threat of slave insurrection left slave owners in a perpetual state of insecurity, compelling them to resort to violence for the slightest infractions. Through violence, slave owners realized their white supremacist assumptions and justified the slave system, fortifying cultural biases that persist today, passed along through generations of prejudice and stifled progress.

Violence upheld the Southern system, not just the slave system. Indeed, the pseudo-feudalistic honour code that bound Southern aristocrats kindled a fetishization of weaponry, along with a permissive view of white slave owners’ right to bear arms in public.

One way in which this culture manifested was in duelling: white Southerners resorted to duelling to resolve controversy far more often than their Northern contemporaries; in fact, the practice had been banned in many Northern states. This enthusiastic embrace of violence also infested Southern legal culture. Modern open carry laws find their precedent in Antebellum Southern court rulings, which held that possessing a concealed weapon was “dishonorable” [sic] and led to “unmanly” assassinations.

These were the seeds of modern American gun culture. Of course, Northerners also bore arms to hunt and for other purposes, but the plantation system birthed a unique romanticization of violence in the South. Naturally, the western “frontier spirit” also romanticized gun culture; however, the rapid settlement of the west was stimulated by the expansion of slavery, as plantation agriculture quickly depleted soil, and slave owners required more territory to establish plantations. Moreover, the slave state coalition recognized that they could only maintain their political monopoly in Congress by establishing more slave states, leading them to encourage western settlement.

No wonder, then, that many pre-Civil War crises were a result of slave owners resisting efforts to abolish slavery in western territories. After the Civil War and the failure of Reconstruction during the 1880s, many “black codes” and Jim Crow laws prevented African Americans from invoking their Second Amendment rights. Meanwhile, white people, with their constitutional right to bear arms, enthusiastically joined the ranks of the Ku Klux Klan and reigned terror on Black communities.

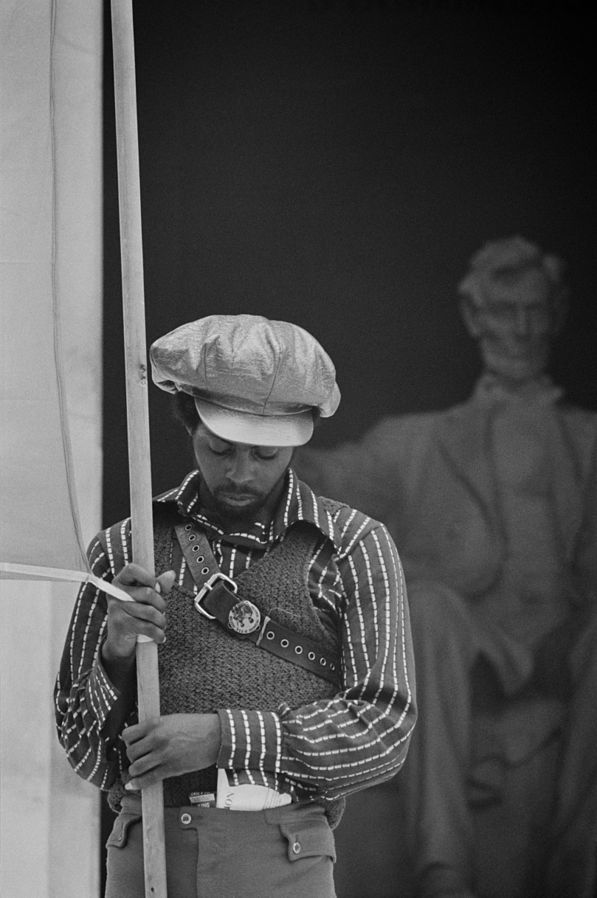

As often in American history, hypocrisy and racism muddy the waters. During the 1960s, the Black Panthers movement would invoke the Second Amendment and open carry laws to defend their right to carry weapons to protect themselves against racists. In response, many states overturned open-carry laws and referred back to the “militia” clause — supported by the NRA and other organizations that are today at the helm of the open carry movement. If their reversal wasn’t hypocritical, perhaps it was out of respect for the Founders’ original intent: the amendment was originally a product of white supremacy, and it had always existed as a tool of oppression.

In time, the Black Panthers dissolved, and conservatives readopted the Second Amendment as a monument to libertarianism. Instead of an agent of the state’s right to oppress Black people, it became every American’s inalienable, nearly unlimited right to resist the overtures of “big government.” But the racist underpinnings did not disappear. Rather, they morphed into the spectre of “big government,” born from a reactionary backlash against government programs and social safety nets that were a direct result of the 1960s Civil Rights movements — and which were predominantly intended to uplift marginalized communities.

This phantom likely influenced Scalia’s decision in 2008. His disregard for grammar and historical context was not a mischaracterization of the Second Amendment, it was a reaffirmation of its original purpose: to oppress Black Americans. The big government “tyranny” he referred to is a euphemism for a government that protects the rights of minorities. Likewise, the idea that every American has an inalienable, unlimited right to bear arms originates in part from a cultural allergy to armed Black people, developed in the Antebellum South and left untreated throughout American history. Even the superficiality of Americans’ affection for firearms can trace its origins to the Southern slave system and the culture of violence that kept it in place. The NRA, and other gun lobbyists who promote an unrestricted interpretation of the Second Amendment are not only impeding recognition of the amendment’s racist history: they are perpetuating racial injustice.

Scalia, and other conservative lawmakers who have gone even further than he did to advance an unlimited interpretation of the amendment, are either blind to the racism that influences their ideology, or content with venerating an artifact of slavery. From its racist political origins at the nation’s founding to racist legal interpretations throughout the 20th century, it remains to this day a haunting reminder of America’s dark past. Although the principle of gun rights may not be racist in itself, those who swear by the Second Amendment and denounce gun reform efforts must recognize that they are effectively defending its racist history. It is difficult to arrive at any other explanation: the laws of grammar and historical context render fundamentalist interpretations indefensible. Presented with these facts, lauding it as a token of American virtue must stem from willful ignorance or racist malfeasance.

Recent months have turned inches into yards as Americans have rushed to the streets, crying out for America to reckon with its racist original sin. Amid these convulsions, monuments have been toppled and false historical narratives have been dismantled. For too long, Second Amendment fundamentalists have succeeded in coating the amendment with a thick sheen of revolutionary tradition. Yet it is like any other monument, and it will prove as hollow as the empty sockets of bygone Confederate statues — a reminder of the US’ misbegotten history and a landmark on the road to its overdue reckoning.

Featured Image: “Holster Gun Flag” by Alien Gear Holsters is licensed under CC-BY 2.0.

Edited by Chris Ciafro