“Opportunity, Innovation, Choice”: How the US Government is Learning to Re-embrace Antitrust

June 11 marked the latest — and perhaps most consequential — development to date of the House Judiciary Committee’s Antitrust Subcommittee’s 16-month probe into the digital marketplace. Under the Subcommittee’s aptly titled plan, “A Stronger Online Economy: Opportunity, Innovation, Choice,” lawmakers introduced five bills targeting the likes of Amazon, Apple, Facebook, and Google.

The Antitrust Subcommittee designed reforms to address allegations of anti-competitive conduct within the tech industry and establish new standards for fair competition across all pockets of the US economy. These advancements toward strengthened antitrust laws signify a changing tide in how firms may operate and Americans may consume their services.

Big Tech as a catalyst for change

Big Tech was born out of innovation and has since evolved along a continuous trajectory to destroy it. These corporations earned their status in the industry by offering specialized and differentiated services, much like any ordinary firm — building, innovating, and achieving unprecedented levels of success. Above all else, the business of acquisition truly propelled Big Tech beyond the likes of ‘ordinary’ firms. Yet, it was these acquisitions that had sent an alarm to Washington. The “winner takes all” model made Big Tech a success story, just as much as it made the digital marketplace a warzone for rising start-ups and capable industry innovators.

In a study conducted by the US National Bureau of Economic Research on more than half a dozen start-ups bought out by Facebook and Google from 2006-2018, there was a consistent trend of decreased investments in smaller companies by forty percent within the first three years following the deal. The resulting substantial decline in market value leaves little to no incentives for innovation. Tech giants employed the “copy, acquire, kill” strategy to exploit existing nuances in the field to strengthen their array of services. The continual acquisition of new start-ups has allowed Big Tech to eliminate and reduce the lifespan of its rising competitors.

In the absence of vigilant antitrust enforcement, leaders can prescribe and manufacture barriers to entry to deter competitors. Deliberate anti-competitive conduct differs from the inherent challenges of entering and remaining in a high-demand environment such as the tech market. For instance, as the leading search engine, Google is the select destination for 92% of all internet searches. Vying competitors to these giants must meet significant capital requirements and face high economies of scale. As a result, the task of effectively building and maintaining a consumer base alone presents itself as an insurmountable obstacle for small-scale tech start-ups. Big Tech’s market domination, which has claimed the minds and attention of so many American consumers, diminishes opportunity.

If passed, this legislation would address issues of preferential treatment to a company’s products and services on their respective e-commerce platforms. It would prevent predatory acquisitions to fuel monopolization, increase funding for anti-monopoly enforcement, and push a more seamless process for consumers to share personal data across different platforms. This legislation is a long-awaited update to antitrust law in America and the most comprehensive effort since the Hart-Scott-Rodino Antitrust Improvements Act of 1976. For those who wish to break up Big Tech, this has brought a new source of optimism and hope for the future. Yet, the advent of such anti-monopoly legislation is a stark reminder of how the government was caught sleeping at the wheel.

A far cry from America’s ‘Gilded Age’ of antitrust

Confronted with the cannibalistic nature of Big Oil in the country’s oil and gas industry, Congress passed the Sherman Act of 1890 and the Federal Trade Commission and Clayton Acts of 1914, leading to the eventual breakup of Standard Oil. Today’s understanding and application of antitrust legislation continue to rely on these three critical pieces primarily. The birth of American antitrust tradition traces back to the end of its Gilded Age, signalling a new era of: “economic liberty aimed at preserving free and unfettered competition as the rule of trade” to be codified in law.

Contrary to the view of opponents of market regulations, antitrust legislation exists as a prominent defender of economic self-determination and the core values of capitalism. In response to World War II and the emergence of fascism, the US government employed this anti-monopoly, pro-competition framework as both a glaring political symbol and a practical tool for promoting capitalism. Antitrust laws represented the democratic embrace of private enterprise that, in all ways, stood opposite the heavily restrictive and state-dictated economy by the likes of Nazi Germany. President Franklin D. Roosevelt recognized the structural similarities between the fascist economic model and the private monopoly’s rule over its industry, calling it an “industrial dictatorship” void of opportunity and financial freedom for both industry players and consumers.

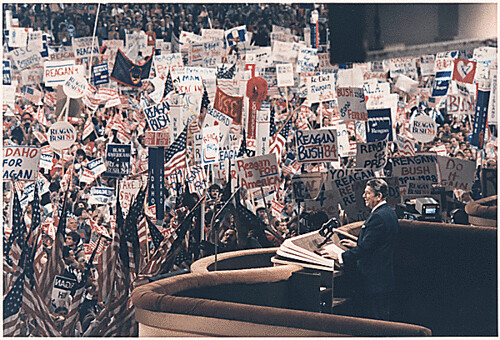

Then arrived President Ronald Reagan in the 1980s, accompanied by his neoclassical ‘Reaganomics’ playbook. The Reagan administration’s efforts to minimize government intervention in the US economy brought a halt to what appeared like a bipartisan trend of presidents dedicated to antitrust as a legitimate and necessary force of market regulation. Trust in the ‘self-correcting market’ and a quickly diminishing belief in the active regulation of monopolies as a policy priority allowed firms to rise without oversight and lay claim to all corners of the ‘free’ market.

Restoring hope in the US economy

Today, it is evident that the government’s push against Big Tech has suffered due to this extended lull in antitrust law development. From their Silicon Valley headquarters, these monopolists possess the means to deter and eliminate smaller competitors, bar innovation, and sway public opinion via online censorship. Yet, unlike the challenges faced over a century ago, the Antitrust Subcommittee now must reckon with powers that do not only unlawfully interfere with domestic competition but may pose a direct threat to national security, American democracy, and economic stability in the age of globalization.

“A Stronger Online Economy: Opportunity, Innovation, Choice” is reminiscent of a revival of the “golden era of antitrust” — an age that reigned before the arrival of the Reagan administration and Chicago school of economics tradition. This bipartisan-backed agenda captures a rare sight in US politics nowadays, rallying support from both Democrats and Republicans against predatory and hostile business practices. To make up for the lost years, lawmakers must work harder to restore fair competition, opportunity, and innovation in the economy. Ultimately, these values go hand-in-hand with a revival of the country’s belief in the ‘American Dream.’

The free market has itself debunked the all-too-popular notion of the ‘self-correcting market.’ Appropriate market regulations must exist to assist and direct the flow of the markets and reinforce pillars of capitalism. These developments in antitrust law should not solely be considered as an isolated solution to Big Tech. Should they pass, they represent a stride towards a strengthened American economy.

Featured Image: “Monopoly” by wwarby is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Edited by Tim Rhydderch