“Persuaded to Return:” China’s Undercover Police Stations Abroad

In October of 2022, Han Yutao’s brother called him from China. Han, a student at Bellevue College in Washington State, had expressed support for the pro-democracy activist Peng Zaizhou. Peng is known as the “Stone Bridge Warrior,” a lone protester who displayed banners that called out Xi Jinping on the Eve of the 20th National Congress, a rare site in China. A few days after he expressed his support, Han said, “police from Zhongguancun West district found my family and knocked on their door. They asked for my mother’s phone number, then called her and asked her where I go to school, when I left China, what I’m studying, then asked for my phone number in the U.S.,” Han says his visible stance against the CCP on campus has led to wariness from other Chinese students; even overseas, speaking out against the CCP can have consequences.

Chinese police in Beijing pressure family of US-based student Han Yutao over support for ‘Bridge Man’ – RFA https://t.co/58mAeLHsyq

— Sense Hofstede (@sehof) October 24, 2022

In 2022, the NGO Safeguard Defenders published a damning report stating that the CCP operates approximately 110 secret police stations across 53 countries. The Chinese foreign ministry claims these are “service stations” intended to assist Chinese tourists and nationals with administrative procedures and renewing their driver licences. Nonetheless, the NGO, whose staff is kept largely anonymous for security reasons, has had its report confirmed by numerous intelligence services and governments worldwide. FBI Director Christopher Wray says the existence of these police stations on foreign soil “violates sovereignty and circumvents standard judicial and law enforcement cooperation processes.”

“Persuaded to Return”

A core aspect of these police stations on foreign soil is the persuasion of Chinese nationals to return home, often to face criminal charges. An official statement from the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI), a government entity of the CCP, states that while official extradition is the ideal, “irregular methods” can also be employed. These methods can include entrapment, kidnapping, and exploiting legal loopholes – actions almost always carried out without the local country’s permission and knowledge. In March of 2022, for instance, a pregnant US citizen was detained for over eight months and told she couldn’t return home unless she convinced her mother to return to China.

The communique of the first plenary session of the 20th Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI) of the Communist Party of China (CPC) was issued on Sunday.

Read full: https://t.co/C9uAdpotOl pic.twitter.com/zeRUq2tf2P— Voice of the People (@VoiceofPD) October 24, 2022

These “persuasion” tactics were operated under the name of “Fox Hunt” until 2015, when the program was transformed into “Operation Sky Net.” The goals of Fox Hunt were expanded through this transformation as the Chinese government’s network became more all-encompassing. Xinhua News, the CCP’s official state media, lists the primary goal of the operation as “capturing suspects of duty-related crimes who have fled abroad and preventing suspects from fleeing.” These stated goals of repressing wire and financial fraud (duty-related crimes) tap into the wider anti-corruption image promoted by Xi Jinping; his anti-corruption campaigns have resulted in the arrest or disappearance of numerous top public officials that most likely threatened his consolidation of power. Since January of this year, Beijing has commenced probes into 41 new top officials.

Since Operation Fox Hunt’s inception in 2014, the Chinese-run CCDI (Central Commission for Discipline Inspection) admitted to the return of approximately 10,000 fugitives to Chinese soil through official channels. However, Safeguard Defenders estimates that over 200,000 individuals have been pressured or threatened to return “voluntarily.” Indeed, Global Times, a newspaper subsidiary of the People’s Daily (a state-sponsored paper), reports that “230,000 telecom fraud suspects [were] being educated and persuaded to return to China from overseas to confess crimes from April 2021 to July 2022.” Both Chinese nationals living out of the country and their relatives who remain in China are intimidated and often threatened to have the individuals return “voluntarily.” It’s clear that the goals of these foreign “service stations” are not limited to simply catching alleged criminals of wire or monetary fraud, as claimed by the CCP; it has the subversive goal of silencing dissidents.

In July of 2021, nine Chinese nationals were charged in “Superseding Indictment,” which alleged conspiracy, directed stalking of US residents, and acting as illegal foreign agents on US soil. The indictment alleges that two of the defendants attempted to force open the door of the two victims’ residence and left a note saying, “If you are willing to go back to the mainland and spend ten years in prison, your wife and children will be alright. That’s the end of this matter!” Although a prominent example, it is not the exception to the rule; this April, two Chinese nationals in New York were arrested for operating an undercover police station on behalf of the Fuzhou branch of China’s Ministry of Public Security.

The United Front System is another method through which the CCP attempts to tap into the influence of expat communities. Safeguard finds that “overseas hometown associations,” while often providing meaningful resources to local Chinese communities, have largely been co-opted by the CCP and their political agenda. In return for their help in increasing the CCP’s soft power and reach, many of these influential community members are awarded political capital and “symbolic appointments” within the CCP. Radio Free Asia reports that on top of the threats made against loved ones, Chinese students studying abroad are often faced with the “prospect of being invited for “tea” with the state security police when they go home.”

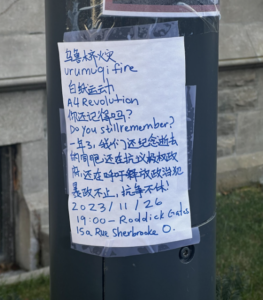

White Paper Protests: Unrest in China

Last year, the grumblings of unrest overtook much of the country. Sparked by a deadly fire in Urumqi, they had been brewing for a long time as Chinese citizens suffered under draconian COVID-19 laws. Demonstrators, who were originally calling for an end to “zero Covid” measures, eventually began to demand an end to censorship and the right to political freedom. Protestors demonstrated by holding up blank pieces of A4 white paper, a striking sign of protest that circumvents the censorship laws upheld by the CCP. M&G Stationery, one of the largest of such companies in the country, eventually banned the sale of A4 white paper for a period of time.

What about Canada?

In November of 2022, the RCMP announced it was already investigating an undercover police station in the GTA, with other such centres being uncovered in Vancouver. In March of 2023, the RCMP began investigating two alleged stations located in Montreal. Tensions between China and Canada have been increasing for years, and the investigation into the two Montreal centres accused of operating as undercover police stations came at a time when there were serious discussions and inquiries within Canadian Parliament regarding potential foreign interference on China’s part in the last two federal elections.

The two centres under investigation for allegedly operating as undercover police stations in Montreal’s South Shore and Chinatown received more than $ 300,000 CAD in federal grants over the past few years. The CCP’s Overseas Chinese Affairs Office officially designated both organizations as “Overseas Chinese Service Centres.” Dennis Molinaro, a former national security analyst and a researcher on foreign interference, stated that “if these organizations have a connection to the Chinese government, getting funding in Canada legitimizes the group, it provides it more of a foothold, it can obviously strengthen it and … give it more opportunities for influencing people.” On December 1st, the two centres threatened to sue for damages if the RCMP didn’t issue an apology for their investigation within the next 15 days.

The implementation of the CCP’s undercover police stations worldwide is part of a larger vision Xi Jinping has for the country’s future on the international stage. Under Xi Jinping, domestic surveillance has increased tremendously, and China’s domestic population has been subjected to more and more authoritarian forms of surveillance. Although its diplomacy has shifted away from the blunt “wolf warrior” tactics witnessed in previous years, the CCP’s desire for a multipolar world means that the general intent behind such diplomatic tactics has not disappeared. Declaring the need for China to “lead the reform of the global governance system with the concepts of fairness and justice[,]” the government’s desire for China to become a leading power means that more subversive actions – such as undercover police stations in sovereign nations – will increase, alongside more visible initiatives, such as the Belt and Road Project. Altogether, Xi Jinping’s push for increasing the party’s international authority indicates his desire to increase China’s prominence on the global stage.

Edited by Darius Jamal.

Featured Image: File:Tank Man Censorship.jpg by D. Thompson is public domain under the terms of Title 17, Chapter 1, Section 105 of the US Code.