Presidential Narcissism: Ego in the Empty Suit

Taking on a political position is sometimes referred to as moving into “service”, entailing a level of self-sacrifice. A person who vies for office need only be a capable individual with strong convictions who seeks to serve the interests of a majority of citizens. Unfortunately, this is not always the case. Because the allure of power seems to attract those with egotistical tendencies, quite often politicians end up only promoting themselves whilst the needs of the masses remain ignored. Nowhere is this more obvious than in American presidential races, where narcissism seems to run rampant.

Narcissism is often defined by four characteristics: a draw to positions of leadership, high levels of self-admiration, a tendency towards arrogance, and an exploitative or entitled nature. Typically, narcissists tend to be self-serving and stop at nothing to achieve their goals. In the political arena, it manifests as individuals who run without clear convictions beyond their own fitness and no distinct policy agenda. It all begins with a grand announcement, often indicating an arrogant belief in the candidate’s individual superiority with little focus on a tangible vision. Then follows an ever-slippery period of platform-shaping. The hope is twofold: appeal to targeted voters while also avoiding any specific promises that may need to be kept once in office. These candidates bury their lack of guiding philosophy in a pile of platitudes and endless flip-flopping on important policy matters without ever making commitments or risking failure.

As ideology inevitably takes a backseat to political ambition, the logical conclusion of this self-serving deceit is clientelism. The candidate will provide promises to wealthy donors in return for significant campaign funds, an act that essentially silences working-class voters. If the interests of their large voter base and those of their wealthy donors conflict, narcissistic actors inevitably bend towards those who helped them most actively achieve their goals.

Sometimes this narcissism is so blatant that it is called out immediately, the clearest example being President Trump with his boastful tweets and inability to take criticism. This trait was already on display in 2016, during his chaotic and contradictory campaign. Bereft with racist dog whistles and typical right-wing grievances against liberal elitism, his campaign, either by genius or simple luck, zeroed in on a vague populist agenda against outsourcing. It is mainly by appealing to Midwestern voters, who had long been the victims of controversial trade deals leading to massive job losses, that Trump secured a victory. Unfortunately, this appears to have been a simple attempt at lying his way into power, a tendency common among narcissistic politicians. Since 2017, outsourcing has increased and Trump’s new trade deals only secured small improvements.

This was not the only bait-and-switch. On the campaign trail, Trump railed against the establishment, claiming he would stop corruption. However, once elected, he packed his administration with Bush administration fixtures and Wall Street executives. He also famously claimed to be “self-funding” his campaign, while simultaneously accepting enormous sums of money from multiple wealthy donors. It is therefore unsurprising that Trump’s tax code now overwhelmingly benefits the top 1%, as this form of clientelism helped propel him into the White House. Evidently, Donald Trump ran for president to feed his ego, and with very little commitment to his base.

While this behaviour has been highly visible with Trump, there also exists a strong vein of narcissism within more mainstream politics. In fact, egoistic behaviour is perhaps more insidious when it is packaged in more typical presidential candidates. Two candidates in the 2020 Democratic presidential primary exemplify political narcissism in action.

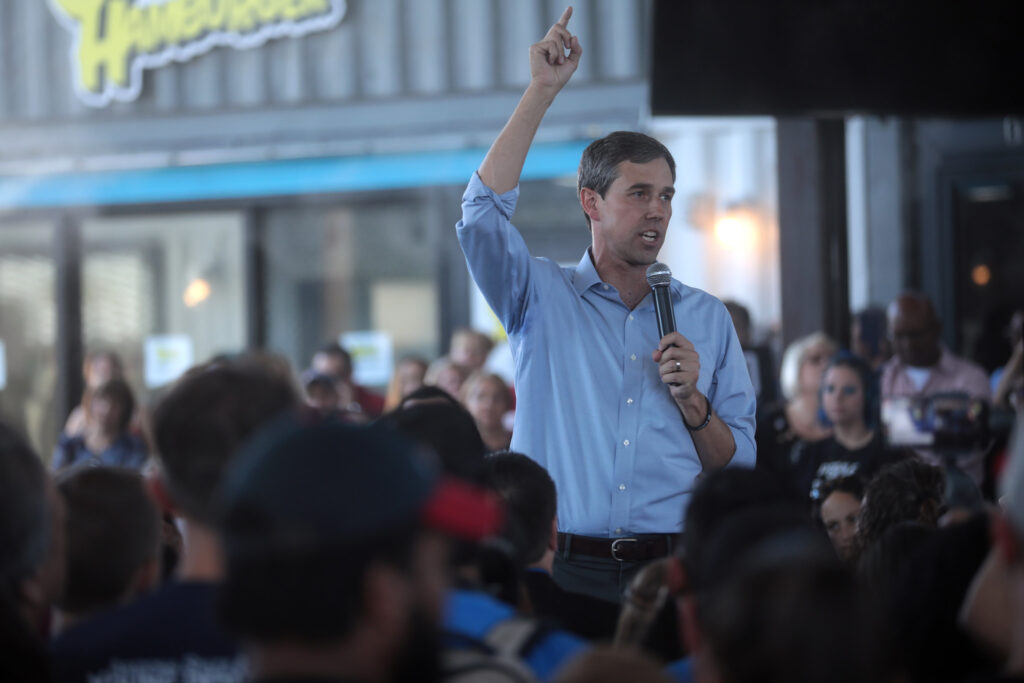

In March 2019, Vanity Fair ran a cover of Beto O’Rourke, sleeves rolled up, on a rural Texas backroad. The quote read, “I want to be in it. Man, I’m just born to be in it.” Fresh off an exciting but unsuccessful run for Senate against Ted Cruz, O’Rourke had a choice: run for another winnable Senate seat or capitalize on recent media attention to propel into the limelight of presidential politics. He had become a political celebrity, amassed a large army of small donors, and a media audience enamoured by his charismatic look. The one thing Beto lacked was a real reason to run for president.

At the beginning of his run, O’Rourke, instead of pushing firm policies, discussed “better things.” He had yet to decide how he would work towards that, and simply justified his run by stating that he was “for everyone,” a belief consistent with narcissistic behaviour. Many began to note that O’Rourke lacked any big ideas of his own and instead delivered platitudes to his supporters. His glittering generalities earned him some support, but the lack of specificity also manifested in contradictory behaviour. O’Rourke stated climate change was an existential threat while accepting fossil fuel money, and he denounced money’s corrupting influence in his Senate run but later accepted large corporate donations throughout his presidential race.

Eventually, when O’Rourke’s campaign began to sputter, he flailed to grab any attention he could. After going viral for his off-the-cuff response to the shooting in El Paso, O’Rourke paired cursing with unnecessarily divisive stances. Not only was this ineffective and counter to his vague platitudes about “unity,” but it also provided a strawman for conservatives to attack, thus dooming any future success.

Much of O’Rourke’s media attention then shifted to a similar candidate, Mayor Pete Buttigieg, who quickly catapulted into stardom. Often, the media’s portrayal bordered on adoration, and headlines such as “Why You Love Mayor Pete” became commonplace. Once again, policy took a backseat to personality. Buttigieg ran largely on his impressive resume: elite educational institutions, military service, a stint in corporate America, and brief mayoral experience. Coverage hovered over superfluous personality quirks such as his multilingual ability, his favourite socks, or his dogs’ personalities. But the media wasn’t solely to blame for overlooking policy; Buttigieg himself painted presidential politics as “a question of what alignment of attributes you desire,” rather than plans for governance. While he insisted on “philosophical commitments” and “values”, there isn’t a history of him taking firm moral stands. In his memoir Buttigieg recounts, without any shame, striding past picket lines for Harvard janitors’ wages to attend a “Pizza and Politics” session with politicians and journalists. He also describes blindly traveling through institutions such as Harvard and McKinsey without acknowledging any of the injustices they foster.

As per the narcissistic formula, the Buttigieg campaign soon turned to flip-flopping on key issues. At the onset of his run, after he had gotten past his philosophical preoccupations, he claimed support of progressive policies. He firmly believed in Medicare for All; opposed corrupting campaign finance laws; and suggested restructuring the Supreme Court. Utilizing these stances and his positive media coverage, he amassed a large number of small donors. Unfortunately, the progressive lane was already crowded, so Buttigieg shifted gears. He became one of the firmest critics of Medicare for All; justified his massive billionaire support by insinuating that small donors were “pocket change;” and dropped his Supreme Court critiques after receiving advice from wealthy donors. Unsurprisingly, his share of small dollar donors fell from 65 per cent to only 29 per cent, and his charming personality stopped being enough to justify his run. Despite all of this, the media still favourably covers Pete, and it seems likely he will run for president in the future.

Until both voters and the media recognize the demagoguery of narcissistic actors — those who try to be all things to all people and will sell voters out to the highest bidder, all in order to achieve higher status — the injustices of the world will continue. Such politicians have no real interest in fixing issues that aren’t politically expedient and simply seek the title of “Most Powerful Person in the World.” These individuals do not deserve our attention or our votes. Until they have proven that they care more about serving society than their own fame, ignoring their efforts to advance it is our best shot at electing efficient politicians.

The featured image Pete For America is licensed as Public Domain.

Edited by Justine Coutu.