Race and Population: Japan’s Economic Timebombs

To address its economic meltdown, Japan will need to turn away from standard financial data, and towards its own historical racism

"Many ascribe falling birthrates to women’s higher education, which has seen growth since the 1970s in negative correlation with birth rates, because as women obtain higher education, they tend to have fewer children." The featured image is courtesy of the author.

"Many ascribe falling birthrates to women’s higher education, which has seen growth since the 1970s in negative correlation with birth rates, because as women obtain higher education, they tend to have fewer children." The featured image is courtesy of the author.

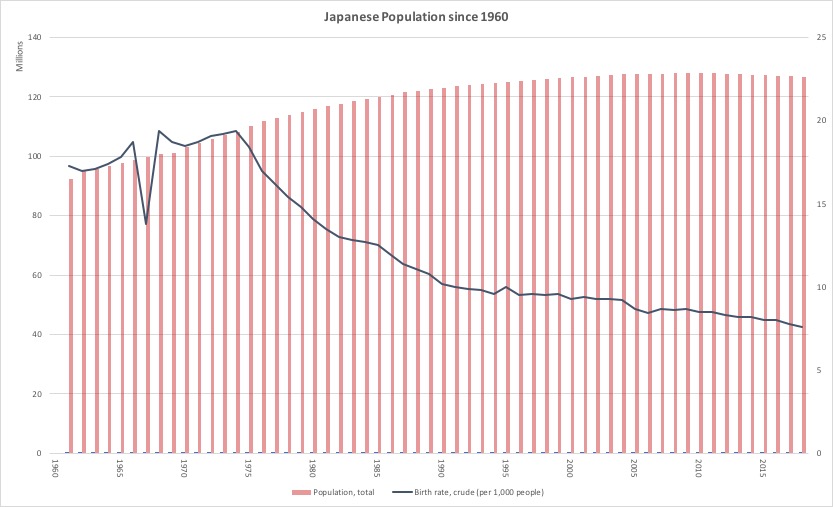

Last week, Masamichi Adachi, chief economist at UBS, summed up Japan’s economy as “very weak, dismal, shockingly bad.” His warning draws on decades of financial disappointment, which have accompanied the country’s rapid birth rate decline. Last year, Japan’s population fell by 430,000. That’s equivalent to cities the size of New Orleans, Halifax, or Sochi completely disappearing, and it all happened in only a year. Since 2008, the country has faced the steepest population decline in the world, unrivalled by war-torn countries or stagnating economies. Last year’s demographic drop is a steady trend the Asian archipelago has been experiencing since the 1970s; now, it’s catching up to its economy.

Demographics are often overlooked in introductions to economics and policy, but they’re essential to any analysis. If populations fall, they take with them supply and demand, tax revenue, total output, and innovation — all frontier matrixes on any economic spreadsheet. Some of history’s most prominent economists obsessed over population. Adam Smith warned that population growth was essential to increasing public output, while Thomas Robert Malthus famously decried it, fearing catastrophic overpopulation. Keynes dreaded depopulation, foreseeing declining outputs and living standards alike.

But with the rapid technological advancements that followed the Second World War, innovation became the key metric with which economists associated growth. Take the Solow Growth Model, the first economic development equation any student of the subject learns, which absolutely dismisses population in favour of technological innovation. Equations like this have been tolerated for decades, but as populations decline, birth rates are returning to the spotlight.

Historical Background: Birth Rates’ Fate

When Japan began its impressive modernization in the 1870s, attention was duly paid to birth rates. The state believed it needed to increase its workforce, consumer base, and military personnel, gearing up for competition against European empires who have a head start on industry and trade. In the late 19th century, the country’s first baby boom helped mold Japan into an industrialized state. Leading up to the Second World War, extensive government propaganda begged the population for more children — and again the people provided. This baby boom lasted into the 1950s, creating the largest elderly population share worldwide at 27%. The generation is now cashing in on their state pension plans and healthcare needs, crippling state finances even further.

Such services might be provided smoothly if not for Japan’s birthrate decline since the 1970s. Baby boomers had fewer children, who in turn had fewer children themselves. Today, the national birth rate hovers around 1.4 kids per family, nowhere near the amount required to maintain the UN-estimated “replacement level” of 2.1. Annually, Japan expects to lose over 400,000 people, rising to 900,000 in the next thirty years. That’s losing a city the size of San Francisco or Bordeaux every year.

So what caused birth rates to decline so rapidly?

Given the country’s sense of urgency, researchers have developed overlapping theories. Some are cultural, like marriage rates and child interests. Today, 10 to 20 per cent of the population don’t get married by the time they turn 50, and even higher proportions of younger generations don’t plan to. For those that do, they expect to marry later, rendering them less likely to have children. Many ascribe this trend to women’s higher education, which has grown since the 1970s in negative correlation with birth rates: as women obtain higher education, they tend to have fewer children. This is true worldwide and has caused divergent feminist critiques. It doesn’t help that today’s Japanese culture expects approximately 27 hours of a mother’s week to be devoted to child care, while expecting only 3 hours from the father. In Canada, we often understand children to cause a pause from one’s career, but for Japanese women, it can mean the destruction of their career altogether.

Finally, the Japanese economy leaves many of its couples too mired in debt and desperation to withhold hope for proper family lives. Though Japan currently enjoys a 97% employment rate, this figure masks deep insecurities. Nearly half of their jobs are impermanent and without benefits. Others demand long hours, working employees to exhaustion (Karoshi, the Japanese word for death-by-overwork, has become a common term). With these strains in mind, it’s easy to understand the hesitation about having one child, let alone 2.1.

Policy Response: State (dis)Solution

Up until now, state solutions have come slowly. Decades ago, the government gambled that automation would maintain output levels without requiring a workforce to manage them, but this technology is still decades away. New spending on welfare has tried to counter pecuniary barriers to having children, but pension plans and state treasuries are being bled by pensioners faster than they can be replaced. Last week, Japan found itself staring down the barrel of its next recession, questioning its potential for growth in the midst of a demographic crisis. Headlines proposing solutions reek of desperation: “Japan’s Demographic Crisis: Any Way Out?” “Can Dating Apps solve Japan’s Sex Crisis?” “Could unmanned ships solve Japan’s population crisis?”

Japan can’t wait for technological automation and it can’t rely on cultural change. But there’s one factor certain to reverse a stagnating population and restore an exhausted workforce: people. Immigrants bring with them more than the money in their bank accounts. Two-thirds of US GDP growth since 2011 can be attributed to immigrants who are twice as likely to start their own business, tend to raise wages in their communities, and receive less government services due to their absence during formative years. And the best part? Immigrants are likely to have more children than Japanese natives.

Origins: Race to the Bottom

So why hasn’t Japan introduced sweeping immigration reform? Racism. Japanese voters fear waves of non-Japanese foreigners flooding their country and destroying their culture. It’s a phenomenon well documented in academic studies, political platforms, and public rhetoric. These fears reach deep into the country’s past, when it was isolated from the world before 1854. Since then, racialized rhetoric comparable to European phrenology and American mythos has established the Japanese as a superior race to neighbouring Asian ethnicities and global cultures. This became even more entrenched with the country’s imperialism, as well as its later experience in the Second World War (known there as the Greater East Asian War).

These events left racial issues that remain untackled. Textbooks don’t mention war crimes, and war memorials don’t mention their cause. The Japanese imperial flag can still be spotted all over Tokyo, an icon of a heroic past unblemished by historic aggressions, colonization, and genocides. In an era where Swastikas and imperialism have fallen out of vogue in industrialized politics, Japanese memory stands out in the developed world as one which applauds its imperialist past. In many ways, they mirror recent Western phenomena, like flying the Confederate flag in the US, or waving a Nazi salute in Europe, but on a much more generalized scale.

Today, Japanese racism actively prevents racial integration. Last year, Japan brought in 161,000 migrants, a record for the country but a relatively small number for its population (Canada, for example, expects twice this number annually, despite having a population three times smaller). Over 40% of those migrants have reported housing discrimination after a landlord refused to lease them a home due to their race — an entirely legal and legitimate action in the eyes of Japanese courts. For example, Baye McNeil is a black man living in Japan who writes frequently on this subject; the Japanese media generally avoids educating the public on such realities. As a result, the state is under little pressure to change citizens’ outlooks and does even less to alter its ethnic breakdown. Racism not only deters prospective migrants from moving to Japan, but it also deters the state from pursuing immigration policies which could be harmful to re-election campaigns. Of 10,000 refugees who applied for asylum in 2018, just 42 were approved.

Implications: What Now?

To effectively utilize immigration as a solution to its falling population, the Japanese state would need to invest a high degree of energy, money, and political capital in deescalating racial tensions. It’s not an appealing project for any government, nor an easy one. “Success” would take time, if it is even possible, but Japan might look to nations like Germany for inspiration. Germany, for reasons of occupation, took an alternate strategy in memorializing its imperial past, banning Nazi imagery, and educating its population on its failures. Improvement will be hard-won, but the intermixture of other ethnicities in Japanese society would accelerate this process alongside its stagnating economy.

Japan isn’t alone in its population problem, as global birth rates’ decline has accelerated in most major states. An increasing concern is placed on the pace of the changing global population, which is expected to peak around 2100 before declining. China, Europe, and the US all project decreasing populations. This has created fears of international stagnation unparalleled in human history. The issues are not disconnected, but a natural aspect of economic development. As education and welfare increase, families tend to have fewer children. If they wish to maintain their workforce while ensuring high standards of living, states will increasingly need to compete for immigration from low-income countries.

Japan is the first of many countries paralyzed in fear of demographic trends. National policy and planning have taken centre stage, but they are currently preoccupied with avoiding migration. This route should be understood for what it is — national economic suicide. Japan prefers to die racially “pure” rather than develop with ethnic diversity. As their economies dance to a steady drumbeat of depopulation, other states eagerly await Japanese innovation. But innovation can’t solve their problem. Immigrants can.

Edited by Albert Gunnison

The featured image is courtesy of the author.