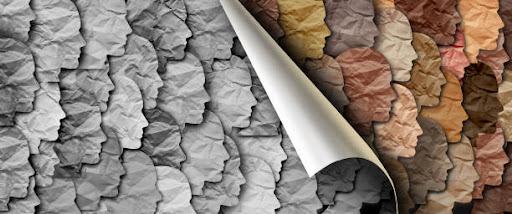

Racialization in a Multicultural Nation: Experiences of a First Generation Migrant in Canada

My lived experience of growing up in small-town Canada as a racialized migrant helped me understand the theoretical incoherence and disconnect between the internationally praised Canadian multiculturalism and the actual attitudes of Canadian society and institutions, which remain riddled with prejudice. Migrants continue to be subject to pervasive marginalization and racialization, in a country that has been legally constituted as “multicultural” with the passing of the Multicultural Act in 1988.

At age four, knowing no English and my understanding of the West being my blonde Barbie dolls, I left Iran, the only home I had ever known with my family. I began my journey of resettlement as a first-generation immigrant in the beautiful small city of Halifax, on the east coast of Canada. My parents, eager to escape the brutalities of the theocratic regime of Iran, were optimistic about our prospects of integrating into Canadian society, leading from the positive experiences of family members in Toronto.

Like many immigrant children growing up in a majority-white region, I have always struggled with my identity due to continued racialization. Throughout my childhood and adolescence, I avoided any engagement with my culture and never came to terms with what it means to be an Iranian coming from the Islamic Republic of Iran.

My lived experiences of racism and xenophobia in Halifax are far from unique, as racial prejudice affects many first-generation immigrants, nor are my experiences particularly harsh, as I acknowledge my middle-class privilege. Today, as a racialized student living in Quebec, I am constantly reminded of the racially charged atmosphere of Canada, leading me to question the core of Canada’s multicultural identity.

Canada’s dedication to inclusivity and multiculturalism was crystallized in 1967 when the Liberal government reformed the immigration system. The former prioritization of European migrants was replaced with a meritocratic system, rewarding immigrants with skills, education and resources and indicating eligibility for Permanent Residency. This “point system” represented a historical moment where Canadian migration policy became “colourblind” on a formal level, as nationality, religion, and ethnicity were no longer factors. The introduction of multiculturalism as official government policy further solidified Canada’s claim to anti-racism, and an open, diverse society.

Since 1971 when Pierre Trudeau prescribed multiculturalism as official government policy, the Canadian nation has prided itself on a diverse and pluralistic identity. Globally, Canada is regarded as a haven free from the insecurities of other, “undeveloped” countries. Migration continues to be the primary vehicle for population growth in Canada, and migrants constitute 8.3 million people and one-quarter of the population. Multiculturalism has become a key aspect of contemporary Canadian socio-political identity. A free, diverse, and liberal country is the claim of the Canadian state, but to what extent are these conceptions the lived reality of migrants, and who are they benefitting?

Despite the multicultural gloss adopted in Canadian institutions, a pervasive Eurocentric identity remains at the core of socio-economic and political affairs. In reality, the requirement for immigrants to integrate manifests itself in key policies, in particular pertaining to language and credential recognition. The Canadian government has declared that English and French languages and cultures are an essential component for integration and “full participation in society.” Furthermore, employers and professionals devalue education and training acquired outside Canada, disempowering immigrants and relegating them to inferior positions.

The term migrant has been politicized and used as a divisive tool throughout the Western world. Migrants are viewed as threats, whether to economic stability, blamed for stealing the jobs of white Canadians and overburdening housing, healthcare and childcare. In extreme rhetoric, we are seen as threats to security and the Nation itself, migrants are painted as terrorists and fundamentalists by media outlets, politicians and political stakeholders. Since 9/11, Canada has experienced persistently high rates of Islamophobia. In 2017, 349 incidents were reported, which was a 150% increase from the year before. Living as a migrant is an undeniably racialized experience.

My immigrant experience is not passive, but an active awareness of my space, language, and body. I walk through life alienated from the space I take up presently while simultaneously feeling the emptiness of the space that I was meant to occupy. I am in constant conflict about where I really belong, and whether separation from my home country and extended family was worth the opportunities afforded by living in Canada.

I live the disconnect between the acclaimed multicultural identity and the actual attitudes in Canadian society, which are riddled with racial prejudice. I experience the dissonance that comes with living in a political society that only accepts and validates certain “cultural” aspects of migrants while simultaneously silencing or mocking parts of other ones. Yes, my classmate David ate my mom’s Iranian food on Multicultural Night, praising the flavour and spices, and yet, he would call my family terrorists when we were in the playground. Migrants continue to feel “othered” as white Canadians gasp at Persian foods, praise our rugs, and comment on how good our English is (the allure and vibrancy of multiculturalism is undeniable), constantly subjecting us to orientalism.

This superficial multiculturalism means that migrants bear the onus of balancing the tightrope of assimilation vs integration in Canada. Since the core of Canada remains staunchly Eurocentric, migrants of colour are forced to assimilate as a survival mechanism in dominant white spaces. As a child, I strived to attain a proximity to whiteness that would allow me to fit in at school and be like the majority of my classmates. I adopted a deep survival mechanism by internalizing racism. I lost my fluency in Farsi, straightened my hair, kept my eyebrows thin, hated my nose, did not take Iranian food for school lunches, and declared myself Canadian. I was surrounded by my friends who were white and belonged to the upper middle class, subconsciously knowing that blending into the norm would be easier than fighting it and facing the social consequences of being “othered”. I sought constant validation from my white peers, always putting in the effort to make everyone else feel comfortable with my appearance and culture.

Despite all my efforts, I still felt othered and racialized by the people around me, from the boys in school calling me a terrorist or “hairy”, to one of my closest high school friends joking about me being the “token brown friend”. These comments hurt because they evoked my deepest insecurities and confirmed my fears of never being able to fit in. But they also proved that no matter how much I tried to assimilate, I still stood out. Whiteness is the default in society, and so, we are forced to orient within it through degrees of assimilation.

Multiculturalism as a policy was a product of its time, and as such, a sign of progress and a corrective movement away from the overt, direct racism of preceding times. It is important that Canadian society does not rest on these laurels. Canada enjoys a reputation as a welcoming safe haven, but to maintain this, it needs to actively fight against current and pervasive perceptions of migrants. It is time for Canadians to challenge their own bias towards immigrants. Canadian legal and political institutions need to address the systemic racism they perpetuate, which plays the biggest role in continuing to marginalize migrants in all walks of life.

Edited by Anya Narang.

Featured Image: Sheida Mousavi’s family by Nikzad Nourpanah.