Salvation or Insecurity? Afghanistan’s Ethnic Politics

Afghan Leaders including Dostum (second from the right) and Abdullah (third from the right), during the signing of a security pact in 2014

Afghan Leaders including Dostum (second from the right) and Abdullah (third from the right), during the signing of a security pact in 2014

Former Mujahideen leader and now governor of Afghanistan’s northern Balkh province, Mohammad Atta Noor has sparked controversy due to his recent refusal to step down from power. An ethnic Tajik, Noor claims that the national government in Kabul led by President Ashraf Ghani, who is ethnically Pashtun, is lazy and corrupt. He also alleges that Ghani is trying to sow discord in his Jamiat-E Islami Party ahead of the 2019 Presidential election. Pledging support for the Coalition of Salvation of Afghanistan (CSA), a political alliance between leaders of several prominent minority groups, many fear that Noor and his political allies will spark greater tension in the already ethnically fragmented nation.

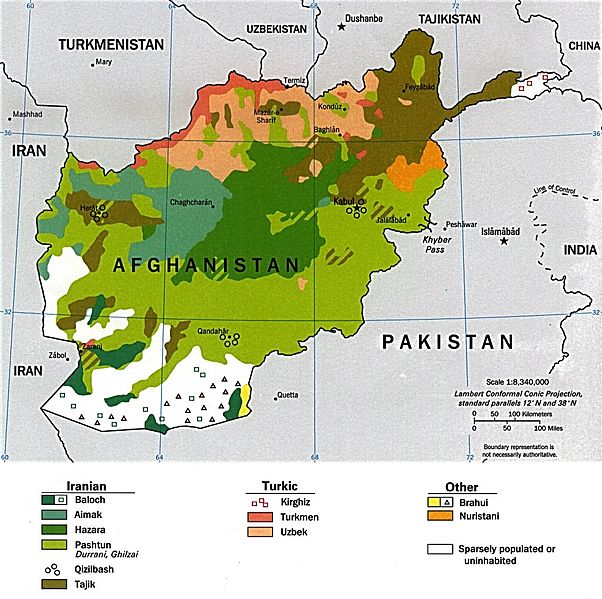

The formation of political alliances along ethnic lines is nothing new in Afghanistan. Having initially been independent, the Northern Uzbek, Tajik, Hazara, and Turkmen ethnic groups were brought into what is modern day Afghanistan by Pashtun King Ahmed Shah Durrani.*

Since the formation of Afghanistan as a nation, these ethnic groups have been subjected to persecution at the hands of the Pashtun majority, with many (especially members of the Hazara community) suffering enslavement and repression from the majority. These ethnic divisions were further aggravated by Soviet policy during their invasion of Afghanistan in the 1970s. Arming the Uzbeks, the Soviets utilized them as military support sending them into battle against Mujahideen fighters in the Pashtun south. This was the first time that the Uzbeks had been given autonomy since their subjugation at the hands of the Durrani’s and saw them alongside the Hazara community seek greater representation in the Rabbani government following the war’s end. During the political turmoil that followed the Soviet withdrawal and emergence of the Taliban, members of the Hazara, Tajik and Uzbek communities banded together establishing the Northern Alliance and fought the Taliban who were primarily composed of Pashtuns. Mass killings such as the 1998 massacre in Mazar-EI Sharif against Hazara, Tajik and Uzbek minorities carried out by Taliban militants, sparked further ethnic division and fear among minority groups in the country.

Formally created in Turkey, the CSA seeks to undermine what it sees as Pashtun hegemony in government. The group’s alliance brings together former allies and enemies from the country’s decades-long civil war. Representing the Uzbek community is former Northern Alliance commander and Vice President of Afghanistan Abdul Rashid Dostum. Dostum was once a prominent militant and has since been a key political player in the nation since the Soviet invasion, fighting against both the Mujahideen and Taliban in recent years. Recently exiled to Turkey from Afghanistan, Dostum is currently wanted in Afghanistan for allegedly orchestrating the torture and rape of political opponent Ahmed Ischi, a former governor of Jowzjan Province. Dostum holds much political clout among his Uzbek community whose interests he has been representing for several years in Kabul, as the leader of the Junbesh-I-Mili party. Another key leader in the alliance is former Mujahadeen and Northern Alliance commander Mohammad Mohaqiq of the ethnic Hazara community. Mohaqiq is the founder of the People’s Islamic Unity Party of Afghanistan and deputy to the government’s Chief Executive Abdullah Abdullah and thus a key part of the current government coalition. The last important leader of the alliance is the aforementioned Muhammad Atta Noor of the Jamaat-e-Islami party. These leaders have key support in their communities, due to the fact that they fought for their interests in the vicious civil war in the 90s, when different ethnic communities were fighting for control over the country. Due to the still feudal nature of many places in the country tribal groups and thus their leaders are still an integral part of the society which manifests itself politically.

The election of Ghani and the formation of the National Unity government in 2014 was based on the careful alliance of various ethnic leaders in the country. In order to gain the Uzbek vote, Ghani enlisted

Dostum to run alongside him for the Vice Presidency. Despite this, it has been shown through the study of several appointments that Ghani favours his Pashtun kin in government positions. Out of 40 appointments made by Ghani to the national unity governments cabinet and provincial government 29 were Pashtun. Chief Executive Abdullah Abdullah, who is serving alongside Ghani as per the agreement made following the 2014 election, has similarly made his appointments along ethnic lines. An ethnic Tajik, 14 of the 23 appointments made by Abdullah were to members of the Tajik ethnic community.

Discontent between the country’s various ethnic groups has been growing and manifested itself in 2016 in the form of mass protests across several Afghan cities. The protests were conducted by members of the Hazara community who said that the diversion of a key infrastructure project from the Hazara dominated Bamiyan province was an attempt to subvert their community’s development. Grievances such as these have fuelled the rise of the coalition for the salvation of Afghanistan. The coalition is calling for the increased government power-sharing with leaders from ethnic minority groups. Due to their role in the fight against Taliban, these leaders feel that they have more legitimacy to their name then Ghani who did not partake in the war. As such they are also calling for all charges to be dropped against Dostum, who played a key role in fighting the Taliban in Northern Afghanistan.

The CSA has also been the recipient of much criticism. Former Pashtun warlord Hekmatyr has said that he believes that the coalition is more focused on gaining back personal power for the disgruntled ex-warlords. Ghani has made similar claims stating that the coalition is angry that they are being cut out of power due to Ghani’s extreme anti-corruption stance. Critics have further pointed out that the coalition calls for more ethnic inclusion, despite having a complete lack of Pashtun representation in their leadership. As such, many say that they are in fact accomplishing the exact opposite of what they set out to do and are increasing ethnic tensions in the country. The Taliban has capitalized on this ethnic division to create alliances with certain key tribal leaders and thus bolster their recruitment in regions across the country.

The formation of this coalition is notable due to the implications it has for the upcoming 2019 Afghan presidential election. As voting in Afghanistan is primarily conducted along ethnic lines, the coalition for the salvation of Afghanistan could become a force to reckon with in the elections next year. In order to maintain his level of support and continue to hold onto power, it is likely that Ghani will have to create a wider appeal to the ethnic minority populations in the country. However, in the long run, continuing to base support and politics along ethnic lines will be detrimental to the country’s success. If politicians are more concerned with garnering support among their ethnic groups then the wellbeing of the nation and its unity then these problems will continue unabated.

Edited by Sarie Khalid

Bibliography:

*Williams, Brian Glynn . The Last Warlord. Chicago Review Press, 2013. pgs, 74-75.