Segregated Suburbia: The Single-Family Home and the Struggle for Integrated Housing

Discussions of systemic racism have dominated media outlets across the United States, with the murder of George Floyd sparking renewed demands for police reform, including calls to defund police forces in order to invest in community-based policing. The COVID-19 pandemic has further illuminated systemic racism, with the virus disproportionately affecting low-income and racialized communities. In New York City, eight of the ten neighbourhoods with the highest death rates have predominantly Black or Latino populations, while those with the lowest death rates all have six-figure median household incomes, and all but one are majority white.

These issues highlight how US cities remain heavily segregated by race and income level. Everyday interactions with police and the ability to social distance during a pandemic are just two of the most visible examples of how lived realities can vary according to your ZIP code.

When the Fair Housing Act was passed in 1968, it promised integrated housing by outlawing explicit racial discrimination in selling and renting homes. However, segregation not only persists, but is on the rise — although US cities have grown more diverse over the past 50 years, the neighbourhoods within them remain divided by race.

Despite the ban on racial discrimination, another source of segregation remains intact in the US: economically discriminatory policies that exclude low-income Americans from entire neighbourhoods, most commonly in the form of single-family zoning laws. In effect, single-family zoning excludes Black, Indigenous and People of Colour (BIPOC) from richer and whiter neighbourhoods — often areas with better access to transportation, employment, and schools. Zoning laws determine where and how people live, and undoubtedly contribute to other forms of systemic racism in the United States.

The History of Zoning American Cities

Although invisible on land and often inscrutable on paper, zoning laws are responsible for how cities are constructed and the way people live in them. In the early 20th century, US cities began to adopt zoning ordinances due to rapid urbanization and industrialization. Early zoning laws were designed to prevent nuisances in residential areas, such as Los Angeles’ first municipal zoning ordinance (1904), which prohibited public laundries and wash houses from entering residential districts.

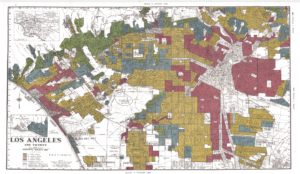

Alongside factories and high-rise buildings, early 20th century zoning laws deemed Black individuals a nuisance to residential communities across the segregated United States. Although the US Supreme Court ruled in Buchanan v. Warley (1917) that racial zoning is unconstitutional, lawmakers and city planners found loopholes to keep racial segregation intact. Jim Crow laws remained virtually unchanged in the Southern US, upholding the “separate but equal” narrative that condemned African Americans to inferior treatment. In the 1930s, redlining, the practice of banks disproportionately denying mortgages to BIPOC because they were considered “high-risk” for defaulting, became commonplace.

While Jim Crow laws were abolished with the 1964 Civil Rights Act and redlining was prohibited under the Fair Housing Act of 1968, exclusionary housing practices still endure in the form of single-family zoning laws. In response to the 1917 Buchanan decision, cities across the United States adopted zoning laws preventing the construction of duplexes, triplexes, and apartment buildings in white neighbourhoods. In 1916, only eight cities had single-family zoning ordinances, but by 1936, 1,246 cities adopted single-family zoning. The commonly used argument that multi-family dwellings ruined neighbourhood character was ruled constitutional by the US Supreme Court in the Euclid v. Ambler (1926) decision, stating that single-family zoning was linked to public welfare.

The Dark Side of Single-Family Zoning

Single-family zoning is ubiquitous across American cities, with detached, single-family homes accounting for over 70 per cent of all residential land in cities such as Charlotte, Minneapolis, and Los Angeles. At face value, exclusively building single-family dwellings in neighbourhoods does not seem particularly insidious, but single-family zoning is so detrimental due to its indirect impact — pricing out low-income communities. Single-family zoning effectively bans all other types of housing, such as apartment buildings, student housing, and low-income housing, disproportionately impacting Black and Latino communities. When entire neighbourhoods are restricted solely to those who can afford to buy or rent single-family homes, they remain enclaves for the rich and white, preventing the development of more integrated housing.

Residential segregation not only endures, but is on the rise due to processes such as gentrification that are facilitated largely through zoning laws. Between 2003 and 2007, the City of New York rezoned nearly 200,000 properties in the hopes of stimulating housing developments across the city. New York’s city council voted to decrease residential densities in wealthier areas, while “upzoning,” or increasing density in low-income neighbourhoods. Although the rezoning projects did not mention race, they resulted in the disproportionate displacement of the city’s minority communities. For example, in Park Slope, although rezoning successfully added over 6,000 households to the area between 2000 and 2013, this was also accompanied by a decrease of 5,000 Black and Latino households over the same period, as new housing projects drove up the cost of living.

Worsening housing segregation by income level is a cause for concern, because the neighbourhood someone lives in affects so much of their lives — their well-being, access to decent health care, and the opportunity to send their children to better schools. Families in poorer neighbourhoods do not have the same access to health care, as seen in the example of Washington, DC, where the affluent suburb of Bethesda has one paediatrician for every 400 children, compared to the poor and predominantly Black Southeast DC, where there is one paediatrician for every 3,700 children. Housing segregation also manifests in the public school system, as approximately three-quarters of students in the US attend the school nearest to their homes. As students from low-income and racialized communities are unable to attend better-funded schools in wealthier neighbourhoods, higher education and employment outcomes continue to diverge on the basis of race and income.

Moving Beyond The Single-Family Home

Acknowledging the negative impacts that single-family zoning can have on low-income communities, cities and states across the US have introduced legislation greatly reducing the amount of land allocated to single-family homes. In July 2019, Oregon passed legislation legalizing duplexes, triplexes, and attached townhomes in cities of more than 25,000 people. While not explicitly banning single-family zoning, the bill leaves few towns in the state where single-family zoning is still operable.

In December 2018, the Minneapolis City Council went one step further by voting to get rid of the category of single-family housing, allowing residential structures with up to three dwellings in every neighbourhood. Despite not mentioning high-rise buildings or condominiums, this legislation faced opposition from local groups fearing that the city’s plan would result in the bulldozing of entire neighbourhoods. However, as housing costs have skyrocketed and housing shortages have grown worse since the 2008 financial crisis, single-family zoning has increasingly come under attack as a barrier to affordable housing.

Single-family zoning is practically gospel in America, which is why proposals to limit the ubiquity of single-family homes feel sacrilegious — it belies one of the most iconic symbols of the American Dream, that if you work hard enough, you can buy a house in the suburbs surrounded by a white picket fence. Of course, the possibility of achieving the American Dream was for a long time not afforded to African Americans, a lasting legacy of centuries of slavery and segregation. Despite de jure housing segregation ending with the Fair Housing Act of 1968, American cities remain highly segregated by race and income level, largely due to single-family zoning. Although today’s exclusionary zoning policies do not explicitly mention race, the American myth of the single-family home continues to stand in the way of equitable and integrated housing across the nation.

Featured image: Suburbia Texas Style by Wayne S. Grazio is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Edited by Chino Ramirez