Selfish Altruism: Lessons from the Remdesivir Buyout

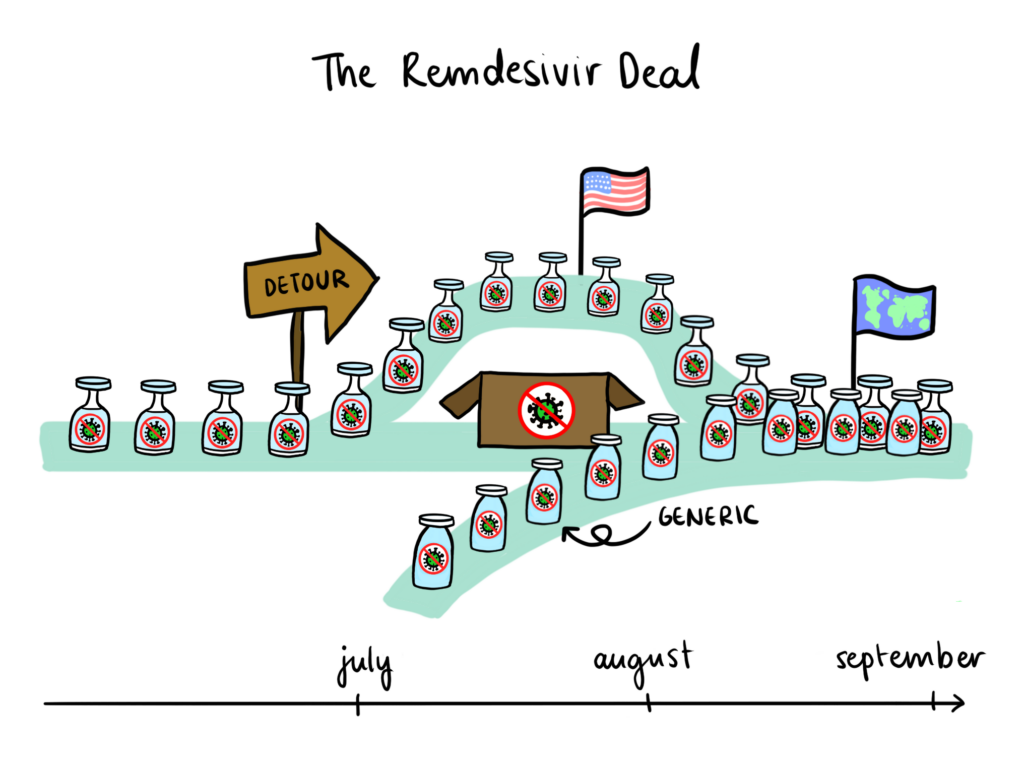

The steady tick, tick of the counter for confirmed COVID-19 cases worldwide pays no regard to news that as of the first week of July, the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) has bought out nearly the entire global supply of remdesivir for the upcoming months. The antiviral drug is one of few supportive medications for COVID-19 patients, and represents for many a last glimmer of hope as clinical trials for its alternatives are discontinued. It is unsurprising, then, that the deal struck between the HHS and remdesivir manufacturer Gilead Sciences, which secures 100 per cent of Gilead’s projected production for July and 90 per cent for August and September, was met with fervent unease.

Given the capricious nature of the pandemic, the degree to which this deal might threaten global health responses over the coming months remains unknown. According to Thomas Senderovitz, who leads the Danish Medicines Agency, Denmark has enough of a supply of remdesivir “to make it through the summer if the intake of patients is as it is now,” though there is fear that challenges may arise if a second wave is to occur. However, what is certain is the greater concern that the unprecedented buyout “signals an unwillingness [for the US] to cooperate with other countries.” Calls have been made for the establishment of stronger frameworks that guarantee fair pricing for and access to “key medicines.” Yet, a deeper dive into the history of pharmaceutical giant Gilead may provide insight as to how the remdesivir deal might be an unsuspecting candidate for executing the very results sought by critics.

In early 2019, Gilead was the face of an innovative new market model known to health economists as the “Netflix” model. At its core, this model involves two agents: the manufacturer (in this case, Gilead) and the payer (the state of Louisiana). In exchange for some lump sum payment, the manufacturer provides the payer with unrestricted access to a drug, originally intended as a treatment for hepatitis C, and both parties benefit — the payer negotiates a reduced price for the medication, while the manufacturer is guaranteed recovery of production costs. The terms of the Louisiana-Gilead contract ensure accessibility and affordability of the hepatitis C drug, and Governor John Edwards is confident that this deal is “a big step forward” in the effort to eradicate hepatitis C in Louisiana. Meanwhile, until 2024, Gilead will have a monopoly on hepatitis C treatment drugs across the state.

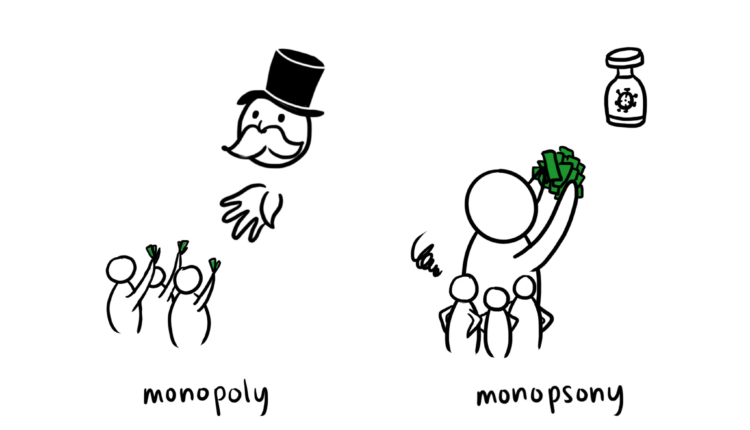

When it comes to single-entity market structures in pharma, the rules of microeconomic theory are distorted. Monopolies are often blamed for drug price inflation, as a single player in control of the market supply implies that competitive pricing schedules need not apply. Still, and perhaps counterintuitively, monopolistic market structures can derive benefits that instead lower drug prices and resolve health care inefficiencies, as evidenced from the Louisiana-Gilead contract. Monopsony, on the other hand, invokes a similar fear but for a different reason: it implies a single buyer has the power to restrict product access to everyone else. Assuredly, Gilead’s return to the world of single-entity markets has been marked by such reactions in light of the HHS’s exclusivity mandate on remdesivir.

Despite monopoly and monopsony being diametrically opposed, a common thread may account for motivations in pharma to opt into single-entity markets and the potential for net gains. Sachin Jain, adjunct professor at Stanford University, identifies risk mitigation to be a fundamental consideration drug manufacturers and buyers alike must make in the contract drafting process. The Louisiana-Gilead contract, for example, frees Gilead from risk of incurring losses, while up-front price negotiations grant the Louisiana health department immunity against rising costs and budget cuts. With this model, altruistic intention is not a necessary condition that must be satisfied for an ample supply of hepatitis C medication to be secured for the public.

In a similar way, a net benefit for COVID-19 patients worldwide can be derived from the individual gains of Gilead and the HHS. Though there is no immediate threat of a demand shortage for remdesivir any time soon, remdesivir has yet to pass clinical trials and holds only emergency use authorization in the US. Faced with the reality that several once-promising drugs for supportive recovery have since been abandoned — including hydroxychloroquine and lopinavir/ritonavir—there is substantial risk that remdesivir may be similarly ill-fated. Moreover, rocketing infection numbers have branded the US as “the globe’s leader in coronavirus cases,” and the HHS has committed to ensuring that “any American patient who needs remdesivir can get it.” Given current data showing remdesivir to expedite recovery time, the drug is an attractive tool for enhancing patient flow. It follows naturally that Gilead and the US mutually benefit from a contrived deal.

Just as the single-entity market structure of the Louisiana-Gilead contract provided a mechanism for increased affordability and accessibility, there is reason to think that the short-term monopsony on remdesivir promotes the growth of global remdesivir supply. Indeed, Gilead has signed non-exclusive, royalty-free licensing agreements with generic pharmaceutical manufacturers in India, Pakistan, and Egypt, aiming to distribute remdesivir in 127 low- and middle-income countries fighting the pandemic. Furthermore, medical officials around the world are confirming adequate supplies of remdesivir for the immediate future and existing remdesivir stockpiles have been donated by Gilead to ensure current patient needs around the globe are met. Setting speculations of malicious intent aside, this monopsony is largely responsible for mobilizing drug access at the international level.

Ultimately, the remdesivir deal is a testament to the complexities that drive multilateral responses to a global pandemic. There is a clear urgency for nations to adapt to novel market structures whose unfamiliarity may be frightening, but with a coordinated international effort, long-term gains are within arms’ reach.

Edited by Elizabeth Hurley