Social Work is not a Miracle Cure for Systemic Racism in Canada

As the idea of defunding and abolishing the police in Canada becomes more mainstream in the wake of nationwide protests over police brutality and systemic racism, so has the idea of replacing the police with other nonviolent services. In particular, many proponents of defunding the police have called for the replacement of police officers with social workers.

Almost every role in our community a police officer fills would be better handled by a social worker

— ellory smith (@ellorysmith) June 2, 2020

Producer and writer Ellory Smith advocates for the replacement of police with social workers in a tweet liked by over 170,000 Twitter users. Via Twitter.

Those who make this argument typically cite the lengthy education, deescalation training, and cultural competence training that social workers must undergo to practice in their field, compared to police officer training, which is generally much shorter and emphasizes the use of force. However, the rhetoric of social workers as a one-size-fits-all solution to police brutality overlooks the history and current reality of social work as a perpetrator of systemic racism, and how this field uniquely impacts Indigenous and Black communities.

Gitxsan and Amsiwa CBC journalist Angela Sterritt described her reaction to this popular rhetoric on the CBC podcast Front Burner:

“When I started to see people saying, ‘All this money needs to go to social workers’, you know, it was sort of like, record scratch… like, wait, what? Because, you know, for Indigenous people, the social workers are the ones who work hand in hand—and they still do today—with the police to remove children from their homes and place them in residential schools, in non-Indigenous homes, or in foster homes.”

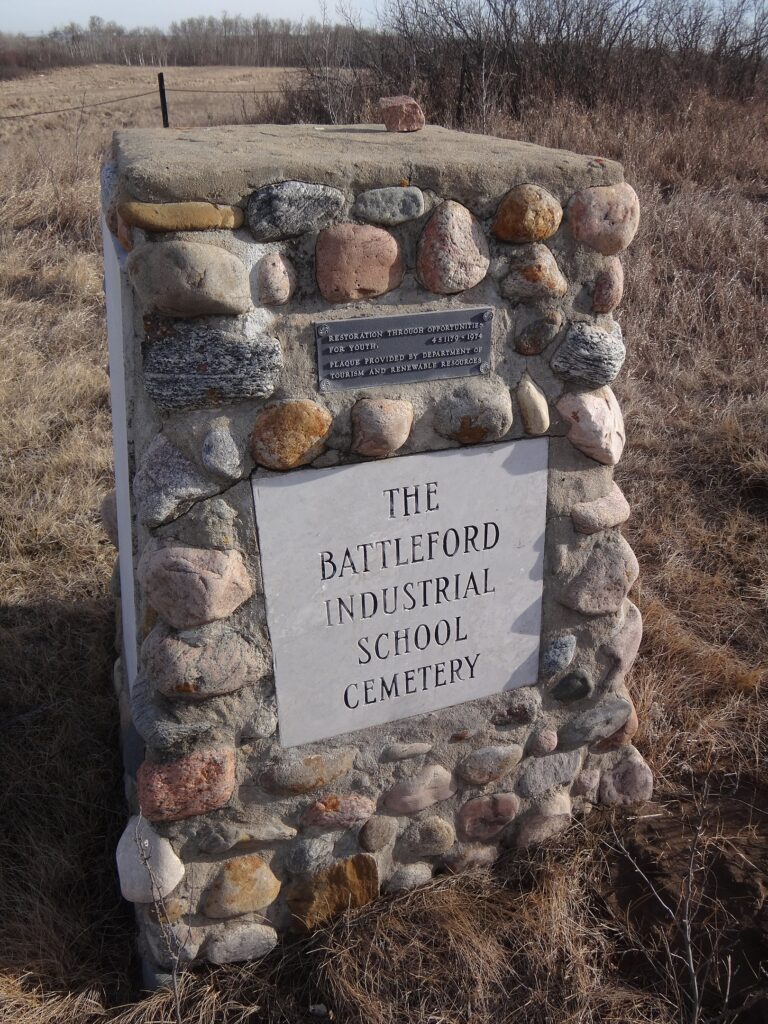

Social workers in Canada have played a primary role in the mass separation of Indigenous children from their families, beginning with their work in the residential schools system. Social workers supported Indian Agents in separating Indigenous children from their families by forcing the children into residential schools. During their time at residential schools, children suffered physical and emotional abuse as the Canadian government enacted its project of cultural assimilation. In total, over 3200 children died from disease and abuse, the majority of which occurred between 1867 and 1940. These conditions were ignored by social workers, who also failed to notify families of deaths in many cases.

As residential schools closed towards the end of the 20th century, the separation of Indigenous children from their families by the child welfare system continued in the form of the “Sixties Scoop”, which extended from the 1960s until the 1980s. Separations were frequently based on Eurocentric cultural standards, as social workers viewed elements of traditional cultures, such as traditional Indigenous foods, as harmful for children. Children were frequently placed into non-Indigenous foster homes or adoptive families where parents frequently lied to their adopted children about their backgrounds, refused to help or allow them to connect with their cultures, and sometimes physically abused them.

The Sixties Scoop is officially recognized as having ended in 1984, however, many Indigenous youth assert that they are now part of a “Millennium Scoop” exemplified by the overrepresentation of Indigenous children in child welfare. Youth speaking on this issue describe being separated from their siblings and being discouraged from exploring their Indigenous heritage, among other stories strikingly similar to survivors of the Sixties Scoop. The Millennium Scoop also continues to perpetuate the use of poverty as a justification for the apprehension of children, separating children from loving homes based on Eurocentric definitions of “neglect”. This disproportionately affects Indigenous and Black caregivers, who frequently receive lower pay than their white coworkers for the same jobs, with the pay gap widening further for women of these communities. Both of these communities are also likely to live on First Nations reserves or in formerly redlined neighbourhoods, where residents are more likely to suffer from institutional financial discrimination.

Although legacies of white supremacy in Canadian social work and child welfare are rooted in anti-Indigenous residential schools, the child welfare system and social work are also agents of anti-Black racism in Canada. Black children in the child welfare system are more likely to remain in the system longer, are less likely to be reunited with their families, and are more likely to be reported to child welfare than their white counterparts despite there being no significant differences in child maltreatment between white and Black families. Black parents are also more likely than white parents to be viewed as “‘aggressive’ and ‘crazy’” by child welfare workers when externalizing emotions such as “resistance, grief, fear or shame”. Black families are also subject to the same Eurocentric cultural standards that Indigenous families are. Two Black children in Ontario were reported to child protection workers on separate occasions for being sent with Caribbean flatbread and Jamaican patties for lunch. Another Black child in Ontario was reported by their school simply for being Jamaican.

Indigenous and Black communities have been speaking out against racism in social work for decades, with the 2015 Truth and Reconciliation Commission and its Calls to Action being one of the most high profile examples. The Nisichawayasihk Cree First Nation has successfully implemented the practice of removing parents from homes, rather than children, as a way to keep children within their community for over ten years. Indigenous activists and organizations have fought for the end of birth alerts in multiple provinces, a practice which separates newborns from their parents and disproportionately affects Indigenous women. The Nova Scotia-based Association of Black Social Workers actively recruits Black foster parents to maintain cultural connections for children. The Black-led One Vision One Voice project is working to end the overrepresentation of Black children in Ontario’s child welfare system by creating and advocating for 11 Race Equity Practices. Indigenous and Black social workers have also continuously spoken out regarding explicit racism in the social work classroom, as well as implicit bias in social work curriculums which have often neglected to acknowledge cultural differences in depth.

These efforts, among many other initiatives, have clearly demonstrated the positive impacts that can arise from rethinking and restructuring social work and child welfare. Some advocates argue that the under-resourcing of social work is the reason the discipline perpetuates trauma in the child welfare system. Advocates for defunding the police argue this problem would be addressed by the shifting of funds towards social work, away from police departments.

However, many arguments for the shifting of funds from police to social workers do not address the racist history and current reality of the field, nor do they distinctly acknowledge the hard work of Indigenous and Black communities both within and outside of the official sphere of social work to remedy this reality. The juxtaposition of these two realities of mainstream, often white-led social work and prevention-oriented Indigenous and Black-led social work demonstrates the need to examine the profession of social work (and other positions within the child welfare system) as critically as we are currently examining policing, and reject narratives that present social work as an inherently anti-racist field.

It is critical that advocates for defunding the police learn and acknowledge the history of social work and child welfare in Canada, the current realities of these fields, and the work that Indigenous and Black communities are doing to change these realities. Furthermore, the work and voices of these communities should be supported with both funds and attention from non-Black and non-Indigenous advocates for defunding the police as they continue to remind those of us who have not had the same experiences with social workers that white supremacy and systemic racism are not only foundational to police forces, but also to other “neutral” fields.

Featured image Defund the Police by Taymaz Valley is licensed for use under CC BY 2.0.

Edited by Jacob Lokash