“Sometimes I Think the Whole World’s Gone Crazy”: The Hyper-Scrutinization of Grime Music

The grime genre emerged from the unique socio-cultural context of East London in the early 2000s, acting as a vehicle for the expression of identity. Grime music is electronic with rap-style vocals, known for its gritty, raw, and unfiltered sound. Grime exposed the lived experiences of predominantly Black, working-class urban youth in London, and gave form to the amorphousness of racial injustice. Grime first emerged as young artists experimented with combining garage and house beats with rap vocals, a sound that resonated with many growing up in London’s inner-city estates. At this time, the New Labour Party in the UK had begun to promote the idea of a Britain that promised prosperity for all. It was clear for many, however, that this vision was not one that included Black Britons, who continued to be overpoliced, denied opportunities, and economically disadvantaged.

Grime was influenced by the long history of Black musical expression in the UK, particularly by Calypso, Reggae, and Ska music brought over by the Windrush generation. Upon the arrival of the Windrush generation to the UK in the mid-20th century, Black British music history reached a turning point, as the use of music as a tool for cultural and political expression began to truly take off. Many of Grime’s founding artists, including Dizzee Rascal, Wiley, and Skepta, have made use of the genre as a political tool, writing and rapping about the plight faced by many Black Britons. Dizzee Rascal, a.k.a. Dylan Mills, one of grime’s pioneers, is touted for the “urgent, high-pitched, staccato delivery” of his hard-hitting lyrics. His first album, “Boy in da Corner,” was released in 2003 and was the first grime release to achieve major commercial acclaim. As a result, Dizzee Rascal became the youngest-ever winner of the prestigious Mercury Prize. “Boy in da Corner” marked a sharp departure from the type of music that was usually recognized by this kind of prize. The album illustrated what it was like to grow up young, Black, and deprived in London’s council estates, exposing the hyper-local dangers and complexities of spending your childhood in a place drained of resources and isolated from the rest of society.

Grime is a grassroots genre that many understand to be a form of English folk music, expressing the identity and shared experience of Black Britons. The diversity of London’s multiculturalism is intimately entwined with the emergence of grime, and the influence of Patois and Arabic can be heard through the mentions of “wasteman” and “wallahi” integrated into so many grime tracks. Grime MCs have, in fact, created their own vernacular language known as Multicultural London English (MLE). MLE is characterized by the development of new slang, largely as a result of the aforementioned influences, as well as changes in pronunciation, speech rhythm, and grammar, and is ubiquitous in grime tracks.

Grime music also has a distinctly local nature, with rappers and MCs identifying their specific geographic origins in song titles, lyrics, and group names, such as Wiley’s “Bow E3” (referencing his postcode), The Square’s “Lewisham McDeez” (referring a specific McDonalds located in the area of Lewisham), and the Newham Generals (named after the Newham General hospital in East London). This notion of ‘repping the ends’ – naming and taking pride in places of local significance – follows a long-established tradition in Black music and is a way of reclaiming places that are often neglected by the general public.

As grime grew in popularity throughout the early 2000s, the media and the government began to respond. In 2006, Conservative leader David Cameron issued a public criticism of grime music for “encourag[ing] people to carry guns and knives” and glorifying violence. Cameron followed this up by adopting a party slogan of “Broken Britain” from 2007 to 2010, promising to take on the “moral collapse” that had befallen his country by commencing a “war on gangs.” In 2011, following the London riots sparked by the police killing of 29-year-old Mark Duggan, historian David Starkey infamously claimed that the problem was that “the whites have become black. A particular sort of violent, destructive, nihilistic gangster culture has become the fashion, and black and white… operate in this language together.” Starkey’s comments are reminiscent of a long-held moral panic on the right, rooted in the fear that Black culture (and Black music in particular) will corrupt white listeners and disrupt the status quo. The 2011 riots were not only sparked by the general systemic inequalities that threatened Black Britons’ lives but also by the fact that the deaths of Black Britons often go unseen and are rarely given adequate media coverage. Rather than acknowledging these issues and their own role they played in them, British media attempted to blame Black people and Black culture for the resultant violence.

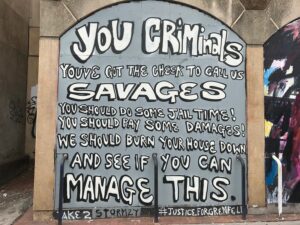

The media also continuously questioned the British identity of grime artists as they continued to garner acclaim. In 2008, BBC journalist Jeremy Paxman interviewed Dizzee Rascal on Newsnight, asking him, “Mr. Rascal, do you feel yourself to be British?” Similarly, in 2018, journalist and former head of media for the Conservative Party Amanda Platell bashed Stormzy’s Brit Awards performance that criticized the government’s treatment of the Grenfell Tower tragedy, writing that he lacked “gratitude” and was “trashing” the country that had “offered his mother [an immigrant from Ghana] and him so much.” Moreover, in 2018, Wiley was invited to Buckingham Palace to receive a Member of the Order of the British Empire, which the Daily Mail commemorated with the headline “Grime Does Pay! MBE for drug-dealer turned rapper.” In all of these cases, the media perpetuates a sense of ‘otherness’ towards grime rappers, attempting to exclude them from British culture while simultaneously expecting them to show it gratitude and reverence.

Grime music was also met with criminalization by the government through the implementation of various legislations. The political right, in particular, began to link grime to an increase in anti-social behaviour that was supposedly plaguing Britain and igniting a moral panic. Specifically, the murders of Charlene Ellis and Leticia Shakespeare were used as an example of the dangers of grime, as the incident occurred due to a gang clash based on the use of mocking lyrics. In the aftermath of the event, grime was further stigmatized and condemned as a symbol of illicit activity and deviant behaviour. As a result, grime music and events became increasingly policed. In 2005, the New Labour Party introduced Metropolitan Police Form 696, a risk assessment form that was required for bars, clubs, and promoters to fill out before music events in London. Still in use until 2017, Form 696 drew widespread criticism due to the excessive amount of personal information it required, including the real names, addresses, ethnicity, and genre of music played by performers, as well as the ethnicity of the audience they expected to attract. Thus, it facilitated the over-policing of Black music genres, including grime. Moreover, in the lead-up to the 2012 Olympics, for example, Newham council removed 76 grime music videos from YouTube that were filmed in the Newham area as part of a “public safety initiative,” furthering the narrative that grime music posed a threat to the general (white) public.

Despite all this, grime has continued to thrive in the UK and around the world, paving the way for new expressions of Black British culture, such as UK drill, and giving rise to some of the biggest names in British music, like Stormzy and Dave. Grime’s resilience and popularity are testaments to the power of music as a tool for expression, even in the face of suppression.

Edited by Zoe Lister.

Featured image: Wiley performing with the grime crew Roll Deep in 2005. Photo by Kevin. Licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.