The Sound of Shattered Glass: Contextualizing Jacinda Ardern’s Victory

Governor-General of New Zealand: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:GGNZ_Swearing_of_new_Cabinet_-_Jacinda_Ardern_2.jpg

Governor-General of New Zealand: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:GGNZ_Swearing_of_new_Cabinet_-_Jacinda_Ardern_2.jpg

Just about two years after gender parity at the Cabinet level was first achieved in Canadian federal politics, a similarly impressive result came to pass in another Westminster parliamentary democracy this past September: a young, unmarried woman was elected to the office of Prime Minister of New Zealand. Make no mistake, however: the ascension of 37-year old Jacinda Ardern to her country’s highest political office was no fluke. In studying the intricacies of the 2017 election campaign, it becomes evident that she possesses extensive political skill in addition to a capacity for transcending a political climate that remains hostile to ambitious young women.

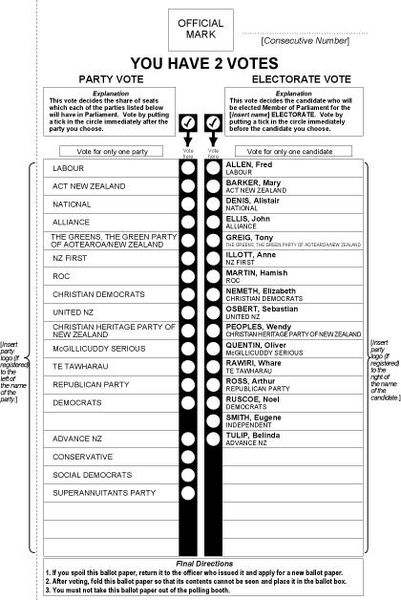

In order to situate Ardern’s political career and the 2017 election result in context, we will first need to examine the electoral system under which her country operates. New Zealand has employed a mixed member proportional (MMP) electoral system since 1996. Under this system, voters have two responsibilities in casting their ballot: they must vote for a party at large, and vote for a candidate in their electoral district. The total number of seats in the New Zealand House of Representatives is divided between electorate MPs, who are elected by simple majority in each of the 71 electoral districts of New Zealand, and list MPs, who are elected based on their party’s overall share of the vote and account for the other 49 seats in the House. Seven district seats are reserved for New Zealand’s indigenous Māori peoples, which makes it unique among Westminster democracies. Each party must compose its own ranked “party list” for list MPs; this ranking decides the order in which the list candidates of one party are elected. Parties must win either 5% of the vote-at-large or one district seat in order to be guaranteed representation in the House. The implications of this system are twofold; firstly, it is proportional, and ensures that vote share of each party corresponds to its share of the seats, and secondly, it often results in coalition governments. This latter implication demands complex negotiations and political compromises, both of which have been commonplace in New Zealand’s post-MMP political history.

While her Premiership is still extremely young and her tenure as leader of the Labour Party only slightly older, Jacinda Ardern’s first involvement with the Labour Party came in the late 1990s; she was also elected as the President of the Union of International Socialist Youth in 2007. Ardern lost her first district election in Waikato in 2008, but became a Member of Parliament due to her high position on the Labour Party list. This same trend repeated itself in 2011 and 2014, as she lost two very close races to Nikki Kaye of the right-leaning National Party in the Auckland Central district. By early 2017, Ardern had become a popular figure within the Labour Party, and was selected as its deputy leader in March. The resignation of Labour leader Andrew Little in July of the same year put the party in an incredibly difficult spot: Little, who had served as Leader of the Opposition since 2014 had resigned amid low poll numbers just shy of two months before the upcoming general election.

Upon her selection as the leader of Labour immediately following Little’s resignation, Jacinda Ardern was faced with a seemingly impossible task: she had scarcely two months to develop her public image, restore her party’s standing in the polls, and oust the incumbent National Party in her first electoral contest as leader. To make matters worse, Ardern was asked a series of blatantly sexist questions mere hours after occupying her new post, which inquired about whether she intended to have children, and the implications this decision could have on her political career. Ardern responded admirably both in professional and moral terms, pointing out the double standard that would never have had reporters asking male politicians such questions about family planning. These questions continued well into the election campaign, one of which asked Ardern about her outfit choices ahead of an election debate. The new Labour leader remained consistent, forcing the interviewer to acknowledge the sexist nature of the question by asking him if he had asked the same question to her opponent, incumbent Prime Minister Bill English of the National Party, a 55-year old male.

Rather than capitulate to unfair, gendered scrutiny from the media, Ardern decided to take matters into her own hands, drawing inspiration from the “sunny ways” of the leader of another Westminster parliamentary democracy. “Jacindamania” was thus born: the Labour hopeful engaged the youth base by vowing to expand access to tertiary education, responded confidently to skepticism from parties both domestic and foreign about the prospect of her forming government, and mobilized human and financial capital alike by attracting a large number of donations and volunteers.

The initial results of the election of September 23rd were encouraging for Labour: while the National Party retained the largest share of the seat total at 56 of 120, Labour surged from its previous result of 32 seats in 2014 to a total of 46 seats under Ardern’s leadership. Given that the National Party had fallen short of the 61 seats required to form government, coalition negotiations were to inevitably ensue. Ardern was faced with yet another colossal challenge; to form government, she would need to secure support from the New Zealand First Party and its populist leader Winston Peters, who had won 9 seats, as well as the Green Party and its 8 seats. After almost a month of vigorous negotiations, Ardern displayed her penchant for overcoming adversity once more, signing a coalition agreement with Peters and the New Zealand First Party, as well as a confidence-and-supply arrangement with the Green Party, securing her the Prime Ministership. The coalition agreements remained faithful to several main tenets of the Labour platform including climate responsibility and economic justice, further demonstrating the Prime Minister’s ability to reach satisfactory compromises.

Amid Ardern’s victory and that of another young and energetic female candidate (the latter in the Montreal mayoral election), it would seem that the fall of 2017 has marked the beginning of an encouraging trend for women in politics. Institutional stigmas that depict family life and political success as mutually exclusive clearly remain, but both victories demonstrate that with enough resolve and resilience, they can no doubt be surmounted, and by extension dismantled. From her initial election as an MP, to her overnight accession to the head of Labour, and lastly to her triumphs both in election and in negotiation, the career of Jacinda Ardern has made one thing clear: no ceiling is safe, and no victory is out of reach.

Edited by: Thea Koper