The Archipelago’s Ascent: Indonesia Waiting in the Wings of the Global Stage

Made up of 17,000 islands, spanning 5,000 km from west to east — the same distance as Montreal to Lisbon — Indonesia is a vast archipelago. Its many islands are inhabited by over 270 million people, making it the fourth most populous country on earth and the largest Muslim one, with over one-sixth of the world’s Muslim population. Indonesia’s median age of 30 is younger than the G20 average and significantly younger than the European Union’s average of 44. The resource-rich country holds deep stores of minerals, oil, forestry and metals and looks set to become the world’s 7th largest economy by 2030, ahead of the U.K. and Germany.

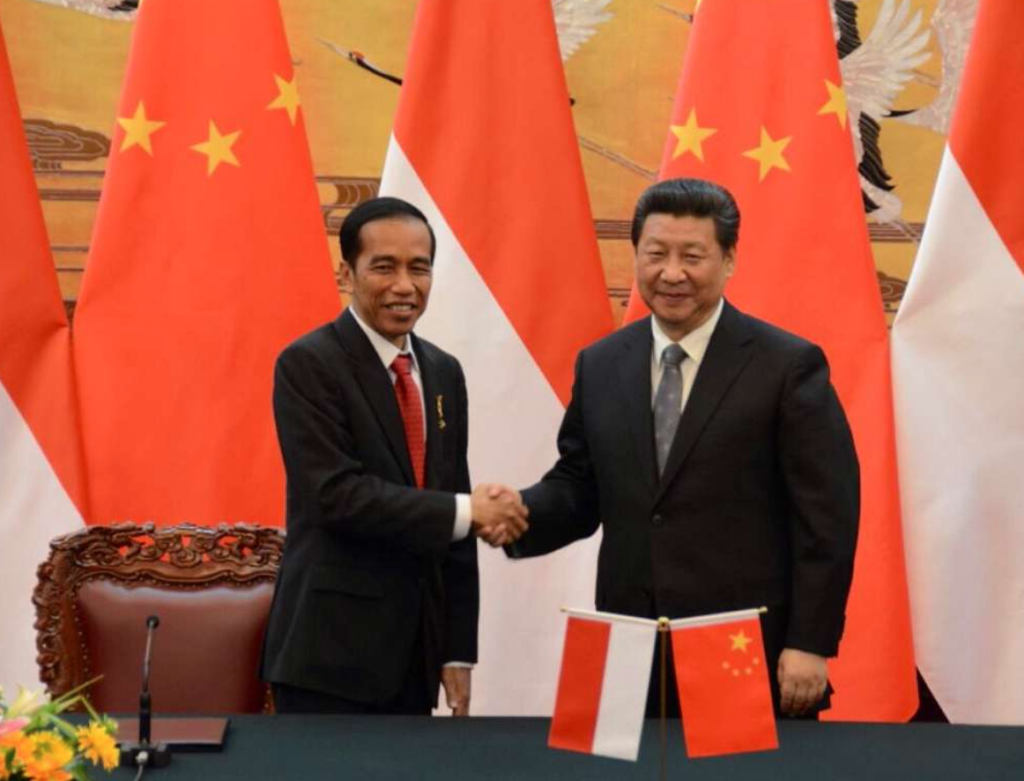

No matter the metric used, Indonesia is a powerhouse. This makes its relative discretion on the world stage astonishing. Some have even argued that it is punching below its weight in global affairs. Recent world events, however, ranging from China’s expansionist policies in the South China Sea (SCS) to war on Europe’s eastern border, have propelled President Joko Widodo — more colloquially known as Jokowi— to increasingly significant roles in global affairs. Consequently, the forthcoming decades could witness Jakarta’s ascending influence on the global stage.

If Indonesia has achieved meteoric growth since independence from the Netherlands, it is because it has harnessed the power of unity in diversity and national identity. Fostering a sense of unity is incredibly challenging in a country of many thousands of islands, with over 300 recognized ethnic groups and 700 languages spoken across the archipelago. The establishment of Bangsa Indonesia, which represents the collective cultural and social identity of what it means to be Indonesian, was a central element of Jakarta’s political project, both leading up to and following independence. Embodied in the nation’s official motto, “Unity in Diversity,” the state has adopted Bahasa Indonesia as an official language and has promoted shared cultural symbols, like the Garuda—a mythical bird deity which gave its name to the Indonesian flag carrier— and a shared history.

The Suharto dictatorship from 1968-1998 heavily emphasized the principle of “unity in diversity” as a cornerstone of its governance. By standardizing education, controlling media, suppressing regional movements, advancing collective economic policies, and ensuring religious harmony, Suharto’s regime aimed to bolster national unity, maintain its grip on power, and prevent internal conflicts. This emphasis on unity was paired with a robust push for inclusive economic development throughout the country. This not only helped reduce inequality but fostered a sense of individual contribution to national growth. This unity has, in turn, led to more stability and a more robust environment for economic growth.

This all remains true today. Indonesia’s tech sector has been growing exponentially, and Jakarta is aiming to become the next start-up capital. Many observers point to the success stories of tech start-ups Gojek and Tokopedia as examples of a flourishing Indonesian tech sector. Entrepreneurs often benefit from the particular sense of Indonesian unity because they could easily scale nationally before going international.

Indonesia has used this increased economic might to flex its muscles more in geopolitical settings. Nowhere is this more visible than in the South China Sea and, in particular, the Malacca Strait, a narrow chokepoint crucial to global maritime trade. Indonesia controls the entire western side of the strait, through which approximately one-third of all global trade passes, about 3.5 trillion USD per year. With Malaysia and Singapore, Indonesia has started patrolling the waters more aggressively, defending its exclusive economic zone (EEZ) against piracy as well as foreign interference, showcasing a more robust stance against territorial infringement. Indonesia is especially wary of Chinese encroachment, from both civilian and military vessels: in 2016, the Indonesian navy shot a Chinese fishing ship in Indonesian waters. Jakarta’s vision of Indonesia as a “Global Maritime Fulcrum” demonstrates the importance Jokowi attaches to the strait and the increasing need to defend it, especially as it allows Indonesia to maintain its positive trade balance with China.

Indonesia’s increased influence has allowed it to have a more substantial impact on decisions within the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). Jakarta was both the driving force and mediator for the Code of Conduct negotiations between ASEAN and China regarding the South China Sea. In 2019, amidst the genocide of the Muslim-minority Rohingya in Myanmar, Indonesia intervened both in its capacity as an ASEAN member and in its own right. Recognizing the potential for spillover, Jakarta leveraged its economic might, political weight, and soft power to engage Myanmar diplomatically and coordinate humanitarian efforts throughout Southeast Asia, embracing its new “free and fair” foreign policy, and contrasting its long-standing policy of non-interference.

Indonesia’s newfound foreign arm is not limited in scope to Southeast Asia. When war broke out in Ukraine in early 2022, Indonesia quickly emerged as a potential mediator. While neutrality on foreign affairs is inscribed in ASEAN’s founding charter, nine of the eleven voted to condemn Russia’s actions in Ukraine – Jakarta abstained from the resolution, repeatedly calling for a peaceful resolution to the conflict instead. At the G20 in late 2022, held in Bali, Jakarta invited Presidents Zelenskyy and Putin, the leaders of Ukraine and Russia, demonstrating its commitment to neutrality and growing potential to act as a mediator in global affairs.

While sound macroeconomic policy has opened the floodgate of foreign direct investment, many questions still surround Jokowi and his democratic credentials. Known as “the man of contradictions”, Indonesia’s seventh president, and the first not to hail from the military elite, is known for his many policy reversals and U-turns. Through various policy changes and political moves, he has firmly placed the judiciary under his control, and many backroom deals, including some to allow his otherwise ineligible son to run for Vice President, have raised eyebrows. The lack of a clear successor to Jokowi has led many to wonder if he is aiming to set up a dynasty for when his term comes to an end next year. This is especially worrying in a country deeply marked by its history of brutal military dictators. Doubts over Indonesia’s political inconsistency and democratic legitimacy may undermine the country’s effort to establish itself as a heavyweight on the world stage.

Indonesia’s potential to emerge as Asia’s foremost power is undeniable. Its immense resources, burgeoning population, strategic location, and growing tech sector provide a solid base. Ultimately, however, its trajectory will be determined by its ability to navigate internal challenges, uphold democratic values, and craft a consistent foreign policy that resonates with its aspirations on the world stage. As the nation approaches a pivotal moment in its history, the choices it makes will shape not only its future but also its role in the global order.

Edited by Daniel Harris.

Featured image: “Jakarta Skyline Part 2” by The Diary of a Hotel Addict is licensed under CC BY 2.0.