The Chinese Problem in Indonesia: A Ghost from the Past that Haunts the Present

The Chinese question is nothing new in Indonesia. Two decades after the post-Suharto reforms, Chinese-Indonesians enjoy greater political freedom and no longer face the coercive assimilation and legislative discrimination they endured during Suharto’s reign. Nevertheless, anti-Chinese sentiments still resonate within society, especially after the election of Jakarta Governor Basuki “Ahok” Tjahja Purnama in 2014. The emergence of Sinophobia this decade can be attributed to a continuation of Indonesia’s past, growing anti-PRC sentiments due to the rise of China on the global stage, and anti-Ahok rhetoric that again fuels the anti-Chinese attitudes at the domestic level. Thus, the story of anti-Chinese sentiments is both historical and current; it is domestic and transnational.

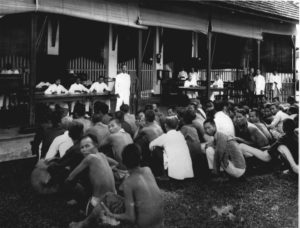

Making up roughly three percent of the entire Indonesian population, Chinese Indonesians have been a dominant player in the economy since the Dutch colonial era. Their strong economic performance and difficulties to fully integrated into local communities due to language and cultural practices made them outliers in Indonesian society. Their “Chineseness” carried a negative connotation that portrayed them as disloyal foreigners. Furthermore, their economic partnership with the Dutch through the trading of sugar and other products and performance as mediators between the Dutch East India Company and local communities were interpreted as cooperating with the enemies of Indonesians. While Indonesian elites also established trade treaties with the Dutch, the Chinese were the scapegoat of indigenous anger because of their foreign identity. This precarious situation made the Chinese victims of violence during economic and political instability. For instance, the notorious killings of ethnic Chinese between 1965 and 1966 demonstrated the hostility directed toward the Chinese population. Going hand-in-hand with the growth of communism in China, anti-Chinese rhetoric has been coupled with fears of resurgent communism in Indonesia. This perception of Chinese as economic exploiters because they traded with the Dutch and the danger of them supporting communism impacted Suharto’s attitude toward the ethnic minority, which increasingly became repressive as Suharto implemented discriminatory policies during his authoritarian New Order government, in which he introduced an aggressive assimilation plan to cope with the Chinese minority.

Under the New Order, Suharto banned Chinese media, Chinese language schools, and Chinese cultural practices. Suharto’s assimilation programs forced Chinese migrants to integrate into local communities by adopting the local language and traditions. While these programs successfully forced the migrants to integrate into local communities, Suharto continued to emphasize Chinese Indonesians’ differences from the rest of the society. Interestingly enough, Suharto himself developed close personal ties with Chinese elite businessmen, which cultivated public dissatisfaction from the Indonesians. Yet, his assimilation program had a temporary effect on containing public discontent toward the administration. When the 1997 Asian financial crisis hit Indonesia and the Suharto regime collapsed, popular anger was directed toward the familiar scapegoat: the Chinese. The historical narrative of Chinese as economically dominant permeated throughout the financial crisis which eventually turned into a series of anti-Chinese riots in May 1998, resulting in bloodshed in Jakarta and other major cities.

Post-Suharto governments have attempted to remedy the situation by abolishing the assimilation policies created under the New Order and by increasing tolerance toward the ethnic Chinese. This loosening of attitudes saw a dramatic revival of Chinese Indonesians’ socio-cultural lives, as Chinese schools, media, and organizations flourished. Despite these assimilation policies, the stereotypical portrayal of the Chinese as economic powerhouses who were hired by the elites to exploit the people continues. Some Chinese Indonesians attempt to debunk this stereotype of “economic animals” by actively participating in politics. The creation of Chinese parties such as the Chinese Indonesian Reform Party (Partai Reformasi Tionghoa Indonesia, PARTI) displayed a change in mood in the Chinese minority after the violence of 1998. This time, the Chinese not only participate economically but also politically.

The trend of overt Sinification during the post-Suharto era and the rise of China as a global power create rifts between the ethnic Chinese and other Indonesians. For generations of Chinese who experienced Chinese education and felt resentment toward Suharto’s assimilation policies, the rise of China as a global power rouses ethnic pride and legitimization. Many Chinese use this opportunity to establish commercial relationships with business counterparts in Mainland China, where their Chinese background and ability to speak Mandarin provide them great advantages. In addition, President Jokowi Widodo has welcomed Chinese investments, including contracting a $5 billion high-speed rail line connecting the capital to the West Java city of Bandung to Chinese companies. His apparent closeness to China, nevertheless, attracts criticisms that his administration is strongly biased towards, and acting in the interests of, Chinese businesses. The awarding of powerplant contracts to Chinese consortia adds another layer to the criticism. Panic over an influx of Chinese labourers into Indonesia and criticisms about China becoming overtly significant in the Indonesian-Chinese trade market have emerged. The negative stereotypes of Chinese as foreigners and disloyal to Indonesia from the past century continue to resonate in the current era.

Domestically, the blasphemy charge against the incumbent Jakarta Governor Basuki “Ahok” Tjahja Purnama during his reelection campaign in 2017 unleashed another wave of anti-Chinese sentiments across Indonesia. As an ethnic Chinese and Christian politician, Ahok’s double-minority identities set him up as an ideal target for sectarian troublemakers. Any dissatisfaction toward Ahok ultimately turned into anti-Chinese sentiments because, to his sharpest critics, he is the epitome of a stereotypical Chinese Indonesian: foreign, non-Muslim, and rich. To Sinophobes, ethnic Chinese have long been perceived as occupying a privileged perch in the country’s economic hierarchy, but now they are also moving upward in the political hierarchy. In addition, Ahok’s close ties with President Jokowi ruffle even more feathers amongst anti-Chinese Indonesians. They are criticized together as bringing Indonesia too close to China and bringing the potential of turning Indonesia into China’s backyard. Thus, anti-Ahok sentiments have been used interchangeably with anti-Chinese sentiments both because of his closeness with pro-China President Jowoki and his own ethnic identity.

Post-Suharto Chinese Indonesian identity politics in the past two decades have been adapting to changing socio-political climates given the rise of China in regional and domestic politics. While populist Islamist groups are gaining political momentum in the country, the Chinese are riding waves of economic opportunities to trade with Mainland China. Chinese businesses have contributed significantly to the Indonesian economy, but this contribution is often associated with negative stereotypes from the past. The difficulty for Chinese Indonesians to find a balance between exercising political rights and maximizing their economic benefits remains a challenge, and their foreign identity and negative historical portrayals still raise questions about their loyalty to Indonesia. Are they Chinese, or are they Indonesian? The economic performance of Chinese diaspora in Indonesia creates friction with local communities, and the exclusivity of the native Indonesian population adds to the difficulty of tackling this ongoing anti-Chinese sentiment. The Chinese question is not new, but the solution to this problem has not yet arrived for Indonesia.

Edited by Jason Li