The Chongryon: North Korea’s Ethnic Enclave in Japan

Japan does not maintain formal diplomatic relations with the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea [DPRK], and when they do meet, their talks often devolve into the difficult issues of Japanese citizens abducted by North Korea during the 80s. However, more than 10,000 students in Japan attend schools which teach allegiance to North Korea, begging the questions why this is, how this enclave come about, and more importantly how have they maintained their way of life in a hostile country?

The answer is found in the Chongryon, a pro-North Korean ethnic enclave in Japan who have maintained a series of pro-North Korean schools since the 50s; it is an organization which, at its height, held more than 500,000 members.

Retrieved from: https://tinyurl.com/y5xwnlbl.

The Chongryon’s Founding:

The Chongryon in Japan are primarily the descendants of Korean labourers forcibly sent to Japan by the colonial authorities during the Second World War.

In 1945, the ethnic Koreans created the Association of Koreans in Japan in order to aid Korean migration back to the Homeland. However, the outbreak of the Korean War caused divisions within the movement, and the Korean Socialists in Japan emerged triumphantly in the leadership race for the organization, whilst the pro South Koreans would form the Mindan.

North Korea lured nearly 100,000 Koreans from Japan with fantastical propaganda promising returnees “Paradise on Earth”. They were unaware it was a land of no return@AFPgraphics pic.twitter.com/y6WjosCErn

— AFP news agency (@AFP) February 21, 2019

This group eventually became the Chongryon in 1955: an organization which essentially ran a state within Japan, as it collected taxes used to run its large networks of schools, in addition to providing ethnic Koreans legal advice, protection, and political representation. The Chongryon was able to survive in Japan as Japanese officials initially viewed the organization and its campaign of promoting migration back to North Korea as a means of reducing the number of Koreans in Japan. In addition, some Japanese politicians, including the once powerful and dominant political lobby in 70s and 80s, the Tanaka faction, worked with the Chongryon under the condition that their business revenue would be utilized in the Tanaka faction’s political machine.

Critically, the organization in the 50s embarked on a program to promote migration back to North Korea, resulting in over 100,000 Koreans in Japan to emigrate to the North, 10,000 of which were estimated to have been placed in North Korean political prison camps after they attempted to return to Japan.

However, those who chose to remain did not assimilate into Japanese society, and the reason can largely be attributed to Japanese citizenship laws, in which Koreans in Japan, termed Zainichi, are deemed to be Special Permanent Residents. This classification hindered the right of ethnic Koreans to Japanese citizenship, even though they were born in Japan and spoke fluent Japanese. This is largely derived from Japan’s citizenship status: citizenship is determined by Jus Sanguinis, in which citizenship is conferred by parent’s ethnicity, rather than Jus Solis, where citizenship is conferred on an individual’s place of birth.

This was problematic, as this hindered ethnic Koreans from obtaining social welfare benefits, legal employment, and social acceptance from society at large, driving many Koreans to join the Chongryon, not because they were Pro-North Korean, but because it gave them a sense of belonging. However, this further ostracized the Chongryon from Japanese society, especially due to increasing fears in Japan over North Korea’s provocations.

The Chongryon and Sense of Belonging for the Ethnic Koreans:

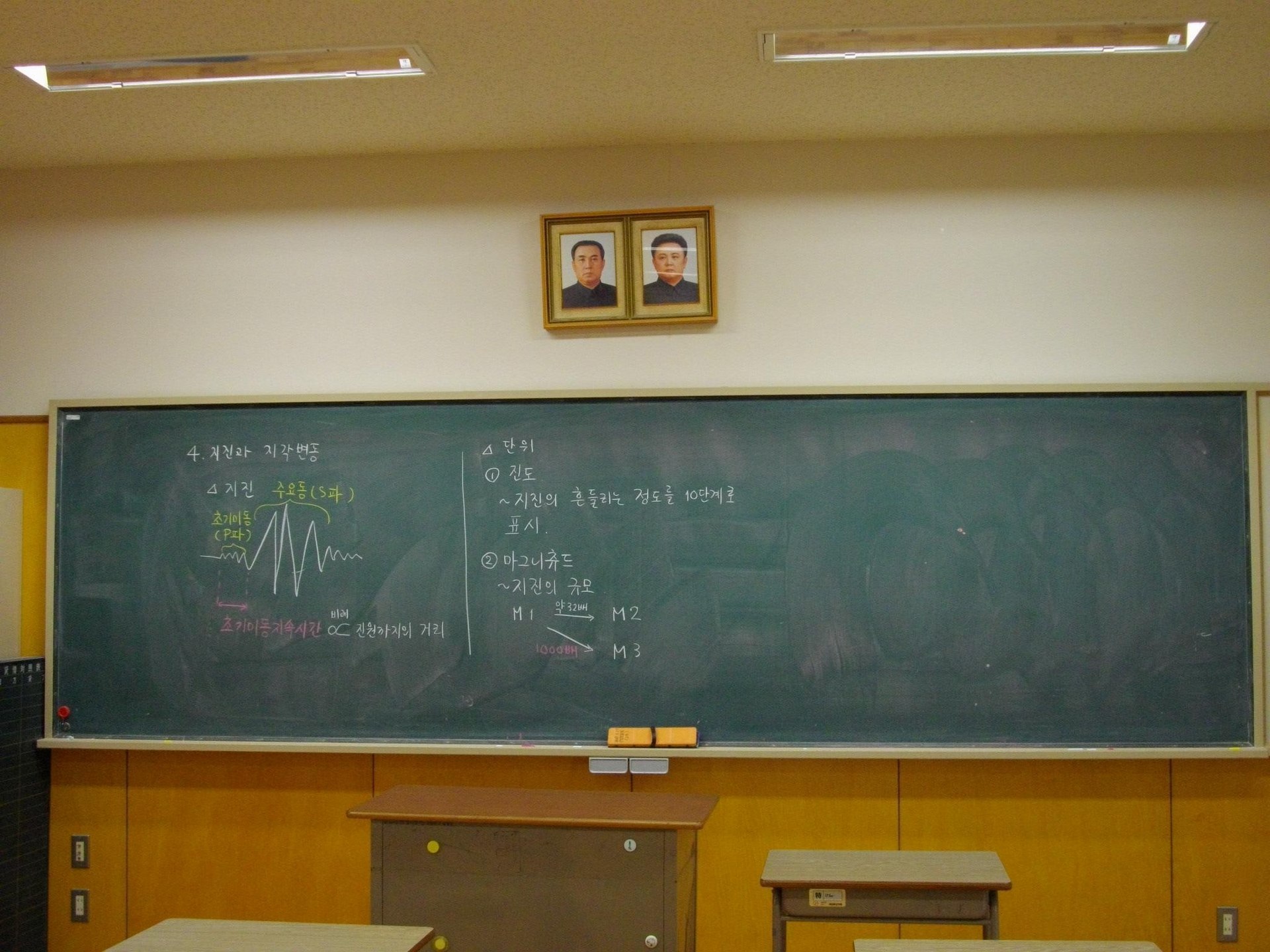

The Chongryon gave the ethnic-Koreans a sense of belonging in a national project through a network of elementary, high-school, and the Korea University in Japan. These schools taught its students diverse subjects such as mathematics, Korean history, and taught North Korean ideologies of nationalism and socialism (there was, and still is, an annual pilgrimage to North Korea).

Retrived from https://tinyurl.com/y5po3m8q

The inculcation of pro-North Korean ideology amongst the ethnic-Koreans who attended these schools were greatly enhanced by the daily discriminations that they faced in Japanese society at large. Economically, many Koreans were traditionally denied good, respectable jobs and were instead employed in low-paying work.

In this context, the Chongryon’s appeal to ethnic Koreans in Japan makes further sense, as the organization provided employment to its members through its quasi-informal business networks throughout Japan. The Chongryon’s economic presence in Japan was largely felt through its dominance of the country’s informal economy such as the Pachinko parlours, a form of arcade or gambling activities, which produced a billion dollars a year in revenue alone during the 80s. At its height in the 90s, the Chongryon’s banking system was valued at over $25 billion.

However, the organization’s power began to decline in the 90s, as the anti-corruption sweeps of the era banished pro-Chongryon leaders from Japanese politics. This, in conjunction with the confirmation of North Korea’s abduction of Japanese citizens, began to harden Japanese public opinion on the issue, and by 2009, the Chongryon closed two-thirds of its schools and the majority of its once mighty business empire.

The Future?

It is difficult to say for certain what the future has in store for the Chongryon. While the young ethnic Koreans in Japan, even those who are educated in Chongryon schools, are increasingly disillusioned of their duty towards North Korea, the fact remains that Japan’s ethnic citizenship laws continue to prevent most of the ethnic-Koreans, many who have been in Japan for over three generations from becoming Japanese citizens. The only hope is that Japan will facilitate the citizenship process for those whose families have resided in the country for over three generations.

Edited by Helena Martin