The Depth of Our Denial: The History of Discriminatory Policing in Canada

Author’s note: police brutality and murder.

The death of George Floyd on May 25 at the hands of Minneapolis police has been a turning point in the fight for racial equality and police reform across the world. For the most part, Canada’s response echoes the Black Lives Matter movement in the United States, with protests demanding justice for Black residents victimized by police violence and calls to reform the current justice and policing system that disproportionately targets Black and Indigenous people. However, Canada’s colonial past, which has informed the use of surveillance and control mechanisms over Black, Indigenous, and other communities of colour, reflects a larger problem in contemporary Canadian society: a denial of the existence of systemic racism which is perpetuated by a history of discriminatory policies and policing.

Canada’s history of racial discrimination and surveillance

Canada’s recent response to police misconduct was primarily motivated by the tragic death of Regis Korchinski-Pacquet, a Black-Indigenous woman who fell to her death after an altercation with Toronto police. Korchinski-Pacquet’s death, alongside other Indigenous and Black deaths at the hands of police officers, emphasized the dire need for police reform in Canada. Data collected between 2000-2017 by the CBC shows that Indigenous people made up 15 per cent of deaths by police despite representing 5 per cent of the population, while Black people represented 10 per cent of total victims and only 4 per cent of the population. A CTV news analysis also revealed that an Indigenous person is ten times more likely to be shot by the police than a White person. Such statistics highlight the undeniable odds faced by Black and Indigenous Canadians when interacting with the police.

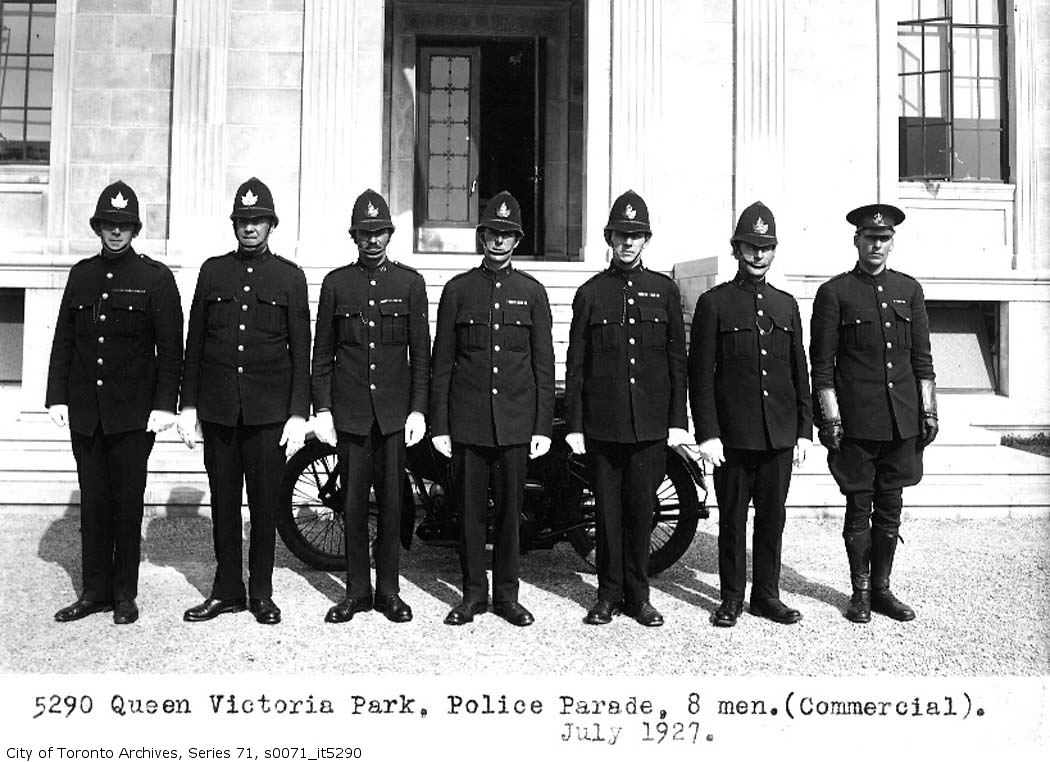

Though Canadians often pride themselves on offering a more inclusive socio-political climate compared to the United States, Canadian history tells a different story. Rooted in colonial practices and notions of white supremacy, Canada’s history is rife with discriminatory policies toward visible minorities that were recommended by the state and implemented by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) and other military agencies. African-Americans escaping the Jim Crow laws in the US confronted Canadian “agents” who were rewarded for persuading them to turn back. Furthermore, the RCMP, along with other military agencies, recommended that Japanese-Canadians be forcibly placed in internment camps to surveil and monitor potential traitors. Discriminatory policing also extended to the control of immigration by certain ethnic groups, such as Chinese and Indians, through strict laws and taxation.

Police as weapons of control and censorship

Canada’s past clearly exhibits the surveillance and control of Indigenous peoples, which, in turn, contributes to extensive legacies of poverty and abuse among Indigenous communities today. Residential schools, a state-mandated program designed to “kill the Indian in the child,” abused Indigenous children and forcibly took them from their parents to indoctrinate them with settler values. In “Colonizing Surveillance,” Chris Proulx, a Métis professor, also argues that “Indian Act Status cards, the reserve pass system (LeRat 2005) and Inuit numbered identification disks (Scott et al. 2004:36-37)” [1] were all employed as methods of state surveillance under the guise of identification. He points to the RCMP’s origins — the North West Mounted Police — as another example; the NWMP protected the Canadian Pacific Railway against “Indians, non-indigenous peoples and their own employees,” [2] negotiated unfair treaties to remove Indigenous people from territories, suppressed Indigenous “uprisings,” and forcibly transported Indigenous children to residential schools. He quotes the Oka, Ipperwash, Gustafsen Lake, Burnt Church, and Caledonia land disputes and standoffs as efforts to suppress Indigenous self-determination and establish military dominance by the state. [3]

The legacy of such policies is illustrated by heightened violence against Indigenous women (prompting the nation-wide campaign for Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls), disproportionate rates of racial profiling and police abuse, and limited access to essential resources and health care in Indigenous communities. This self-perpetuating cycle of discrimination recently manifested in the assault of Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation Chief Allan Adam by police, and the involvement of police in the death of a First Nations woman, Chantel Moore, during a mental wellness visit. Instances of police brutality against Indigenous protestors and climate activists have also been recorded at protests against the Trans Mountain and Coastal GasLink pipelines, which have exacerbated civilian-police tensions and highlighted the frequent use of non-essential force by the RCMP.

Anti-Black racism is also evident in Canadian history, and is a major reason for the creation of modern policing systems. In “Activists and the Surveillance State,” Dr. Aziz Choudry argues that many modern policing practices are based on “counter-insurgency techniques tested against earlier anti-colonial/independence struggles, in policing Black life under slavery and Indigenous Peoples’ resistance.” [4] He states that movements for Indigenous sovereignty and Black justice are framed as “subversion, extremism, terrorism and radicalism” to discourage mass uprisings and to dichotomize Black, Indigenous, and People Of Colour (BIPOC) from non-BIPOC residents.[5] Recent research shows how US and Canadian security services “co-operated to undermine and arguably sabotage” Black activism, with operations such as hiring an American FBI agent who “infiltrated Black and Indigenous activist groups” to encourage violence. This pattern of surveillance has also been replicated more recently. For instance, in 2016, the RCMP was revealed to have surveilled members of Black Lives Matter Vancouver to uncover potential connections to hate groups in the United States.

Police reform: what’s being demanded and what’s being done

BIPOC activists remain at the forefront of the police reform movement. Their agenda includes demanding that officials acknowledge systemic racism, calls to defund the police force, petitioning for more education on BIPOC history, and pushing for the use of independent investigation agencies or community advisory committees to ensure greater police accountability. For many First Nations and Inuit communities, police reform can translate to independent police forces composed of local Indigenous officers. Daniel T’seleie, chief negotiator of the K’asho Got’ine self-government agreement in the North West Territories, argued for this change, stating that “Our people functioned as nations with governance structures and our own laws for a long time before Canada even existed.” Amid growing distrust due to numerous civilian deaths at the hands of the police, turning investigations over to third-party watchdogs has become increasingly routine.

Thus far, the movement’s demands have begun to reach the ears of government legislators. Public Safety Minister Bill Blair promised greater civilian oversight in the RCMP, and Montréal’s Mayor Valérie Plante announced that body-worn cameras will be mandatory for the SPVM. The Montréal police department reported that it will present a new policy for random street checks on July 8. Moreover, the SPVM Chief of Police vowed to “eliminate racial profiling” after a scathing report showed that Black, Indigenous, and Arab people are more likely to be apprehended than White people.

In Saskatchewan, the currently tabled Police Amendment Act 2020 “allow[s] members of the public to monitor investigations where someone has died or been seriously injured in police custody” to ensure greater civilian oversight. The Act also allows the Public Complaints Commission to appoint Investigation Observers, who must be Indigenous in cases where an Indigenous person is involved. Furthermore, it mandates greater availability of report summaries to the public.

Despite some headway being made, activists argue that what has been promised so far is not the end-all for racial justice. Notably, Canada was recently exposed as a major hub for white supremacist activity on online platforms such as 4chan, Twitter, and Facebook. BIPOC activists and allies continue to protest issues such as the unwarranted use of tear gas, vague promises, and the reluctance of the RCMP to collect racial data on those “on the other end of the firearm, taser, pepper spray, or physical restraint.” Concerns over elected officials refusing to explicitly condemn systemic racism are becoming amplified. In order to fully understand recent events, a critical examination of Canada’s racist past and surveillance tools cannot be forgotten.

Though the future of Canadian police reform is unclear, racial justice will only be achieved through the collective effort of non-BIPOC people, government legislators, and civil society. By pushing for transformative reformation in Canada’s policing and justice systems, we can ensure greater accountability, increased transparency, and the unbiased protection of the rights and lives of all Canadians, whether Black, Indigenous, or otherwise.

Feature image: “Canada Day (2009) – Royal Mounted Police” by lezumbalaberenjena is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Edited by Teresa Tolo

Notes

[1] Proulx, C. (2014). Colonizing Surveillance: Canada Constructs an Indigenous Terror Threat. In Anthropologica, Vol. 56, No. 1 (pp. 83-84). Canadian Anthropology Society.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Choudry, A. (2019). Lessons learnt, lessons lost: Pedagogies of repression, thoughtcrime, and the sharp edge of state power. In Activists and the Surveillance State: Learning From Repression (pp. 3-5). Pluto Press.

[5] Ibid.