The DeSantis Effect: How Florida Turned Red This Election Cycle

One week before this year’s midterm elections, Governor Ron DeSantis was outpolling Democrat challenger Charlie Crist by 8.9 per cent. On Election Day itself, DeSantis found himself up 12.1 per cent in the polls, suggesting a firm – but somewhat modest – victory. Yet as the votes began to trickle in, it soon became clear that DeSantis had not merely won by a respectable margin, but by a landslide. DeSantis swept the ballot in Florida, winning 62 of Florida’s 67 counties and beating Crist by more than 1.5 million votes. While the Democrats were largely able to prevent a “red wave” from sweeping the country, gaining control of the Senate and losing just nine seats in the House, they ultimately failed to prevent Florida from swinging rightward, with DeSantis winning by the largest margin of any Floridian governor in 40 years.

DeSantis’ victory on November 8 was not, however, the product of last-minute campaigning, nor was it the result of a sudden shift in the political inclinations of Floridians. Rather, DeSantis’ election night win was a highly calculated effort, driven by a years-long initiative to gain the support of Florida’s Latino population.

“The freest state in these United States”

Upon taking office, DeSantis spearheaded a shift in the party’s campaign strategy, primarily aimed at increasing Republican voter registration and turnout in Florida. DeSantis had, after all, won the 2018 gubernatorial election by a 0.4 per cent vote margin, meaning a victory in 2022 was far from guaranteed. Beginning in 2019, Republican committees organized voter registration campaigns in each Florida county, with Florida Republicans funnelling over $89.4 million USD into party advertising.

DeSantis further built upon the party’s voter registration efforts by positioning himself as a guardian of civil liberties following the outbreak of COVID-19. Throughout the pandemic – and despite a rising case count and death toll – DeSantis fiercely opposed the adoption of lockdowns, vaccine mandates, and mask requirements in Florida, reopening schools and businesses just four months after the pandemic’s outbreak, and proclaiming Florida “the freest state in these United States.” In DeSantis’ Florida, businesses, hospitals, and local governments were legally required to allow employees to opt out of vaccine mandates and school districts were barred from implementing mask mandates.

DeSantis’ pandemic policies held a degree of appeal nationwide, with masses of northeasterners migrating to Florida to escape stringent COVID-19 mandates in their home states. However, DeSantis’ rejection of lockdowns and mandates was, as DeSantis intended, especially well-received by Florida’s Latino population, the vast majority of whom supported DeSantis’ policies. The wealth gap between Florida’s Hispanic and non-Hispanic white populations is stark, with white households earning an average of $10,000 more than Hispanic households each year. By reopening Florida businesses in July, DeSantis enabled Latino families to return to work and earn an income at a time of profound economic uncertainty. Moreover, with elementary and high schools open, the children of families who had recently immigrated to Florida could continue to learn English without experiencing many of the educational setbacks associated with remote learning. Above all, DeSantis’ freedom-based rhetoric appealed to Florida Latinos of Cuban, Venezuelan, and Nicaraguan descent, whose families had immigrated to Florida to flee authoritarian regimes in their respective home countries. Under DeSantis’ governorship, first- and second-generation Latino voters had little need to fear the introduction of lasting government mandates in Florida.

Building on the governor’s efforts, DeSantis’ political entourage attempted to connect with Hispanic voters throughout the campaign period. Seeking to pitch DeSantis’ pandemic policies to Latino voters, Helen Ferré, a Nicaraguan immigrant and Executive Director of the Florida Republican Party, asserted “We know that movie, and we know that never ends well.” Ferré’s allusion to Nicaragua’s history of authoritarian rule – and use of the inclusive “we” – is an explicit appeal to her Nicaraguan heritage, intended to resonate with Floridians of Nicaraguan descent. Additionally, DeSantis’ Lieutenant Governor, Jeanette Núñez, attempted to connect with Floridians of Cuban descent during DeSantis’ gubernatorial campaign. On October 27, just 12 days before Election Day, Núñez tweeted a video of her parents at DeSantis’ inauguration in 2019, captioned “As the daughter of Cuban exiles, I proudly carry their legacy. Hispanic by heritage, American by the grace of God.”

Florida’s rightward swing

As Election Day approached, it became clear that DeSantis’ freedom-based rhetoric had strongly resonated with Latino voters. As a result of DeSantis’ campaign efforts, the number of registered Latino Republican voters exploded in Florida, with Florida Republicans gaining almost 60,000 – and Democrats losing 46,000 – registered Latino voters. With the support of tens of thousands of newly registered Hispanic voters, including former Democrats, DeSantis was able to flip predominantly-Latino Democratic strongholds, such as the counties of Osceola County and Miami-Dade, which no Republican gubernatorial candidate had won in decades. By the end of election night, Desantis had won 58 per cent of the Latino vote, not only gaining the support of 68 per cent of Cuban Americans, who have historically voted Republican, but of 56 per cent of Puerto Ricans, who typically vote Democrat.

During his victory rally, DeSantis acknowledged his inroads with Hispanic voters, proclaiming that the party had gained a “significant” number of votes among formerly non-Republican Floridians. For DeSantis to describe this increase in vote share as “significant” is, without doubt, a monumental understatement. With its population of 5.8 million, Florida’s Latino community comprises one of the state’s largest electoral bases. Armed with a majority of the Latino vote, DeSantis was able to gain millions more votes than Crist, providing DeSantis with sufficient electoral support to win the midterms by a landslide, and to turn Florida crimson red.

In St. Petersburg, Crist offered his own election night speech, assuring Floridians that he was “at peace” with DeSantis’ victory. In acknowledging and accepting his defeat at the hands of DeSantis, Crist was, of course, playing the part of the gracious politician. Florida Democrats, however, should be deeply unsettled by the sheer scale of DeSantis’ victory this November. For Florida to turn blue in 2024, Democrats will need to drastically rethink their electoral strategy in Florida. With DeSantis winning such a large proportion of the Latino vote, Florida Democrats can no longer afford – both literally and metaphorically – to wait for newly Republican Latinos to vote Democrat in the upcoming election. In the inter-election period, Florida Democrats will need to make a substantive effort to reconnect with the state’s Latino community, especially those who formerly voted Democrat, such as Puerto Ricans. Only then can Florida hope to turn blue in 2024.

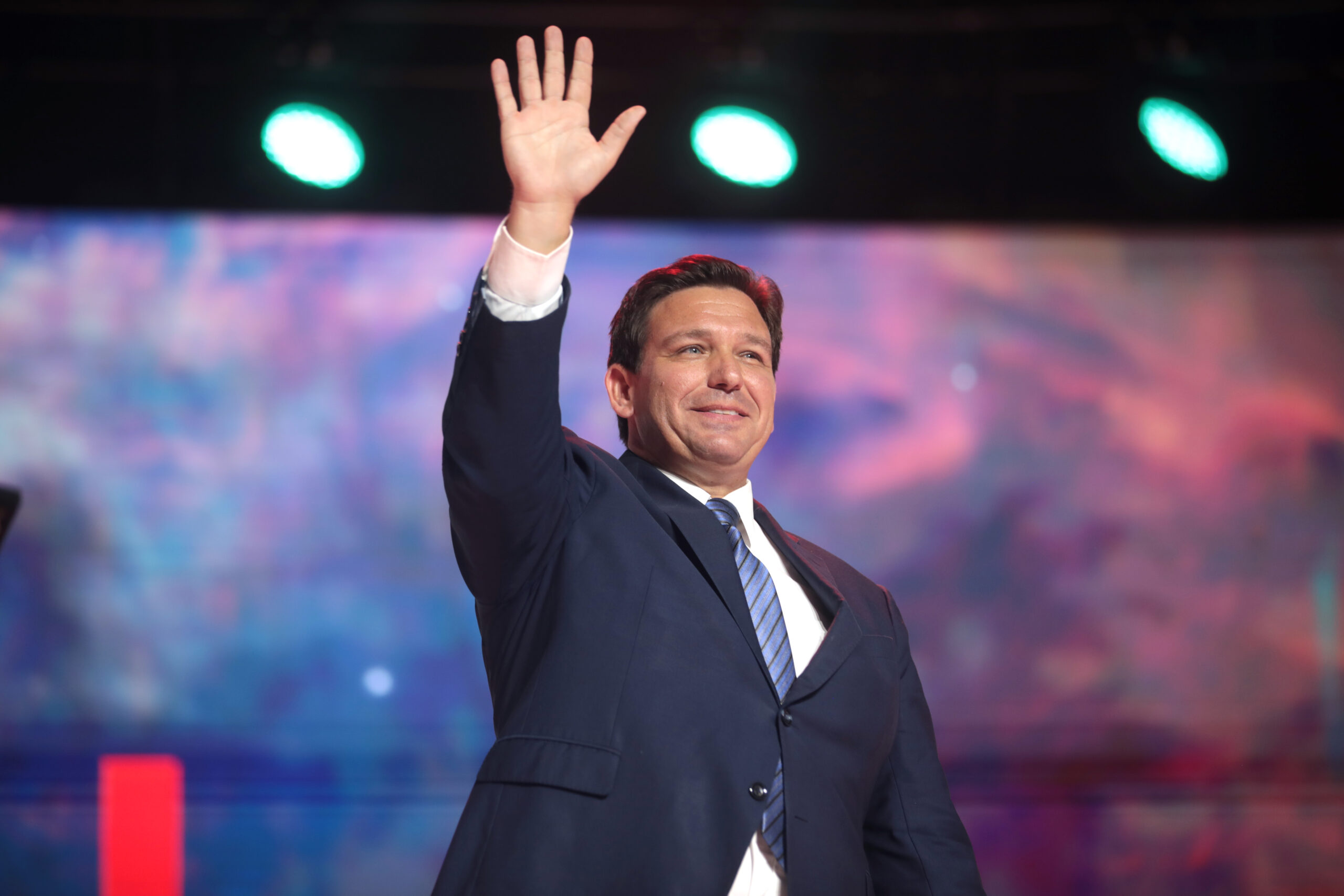

Featured image: “Ron DeSantis” by Gage Skidmore is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

Edited by Skyler Bohnert.