The Extreme Difficulty of Diplomatically Resolving the Ethiopian War

In early November 2021, the African Union envoy – former Nigerian President Olusegun Obasanjo – stated that he saw a “small window of opportunity” to end the ongoing civil war in the Ethiopian Tigray region. However, that slim glimmer of hope now seems elusive, as panic has mounted due to rebel forces claiming more cities in the Amhara region and preparing to launch an assault on Addis Ababa, Ethiopia’s capital city. Abiy Ahmed, Ethiopian Prime Minister and Nobel laureate, responded by putting on a military uniform and calling for public rallies on Facebook, vowing to “lead troops in the war against advancing Tigray rebels.”

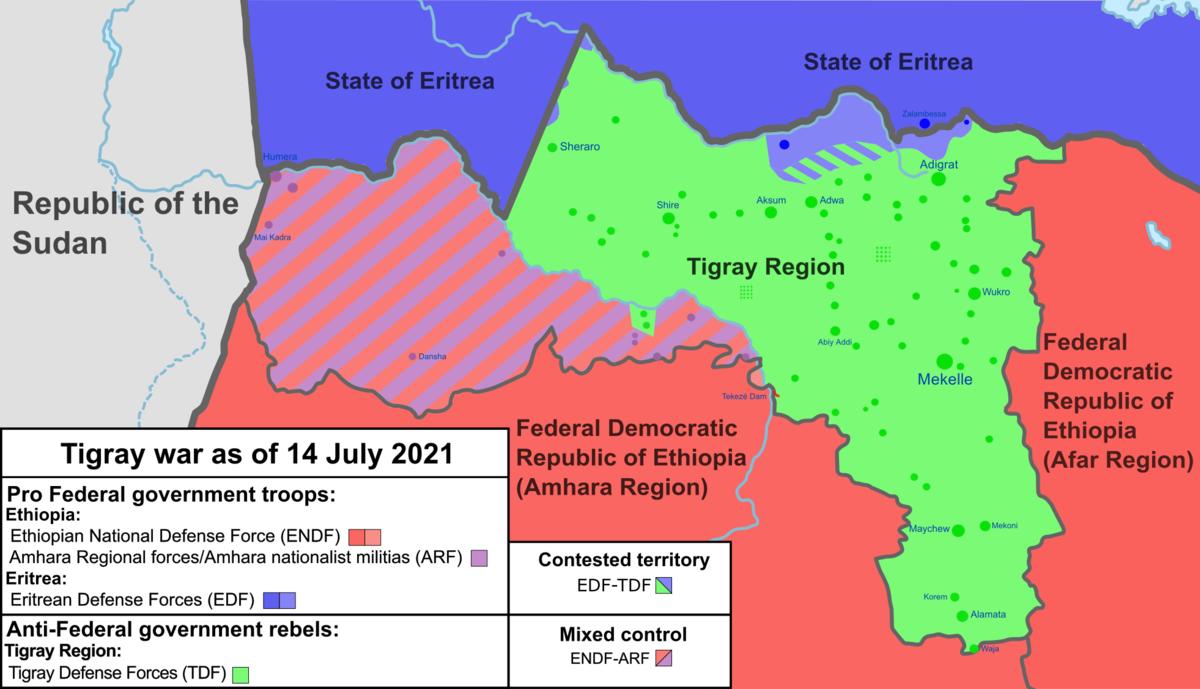

The conflict was sparked in November 2020 by clashes between the federal government of Abiy Ahmed and the Tigrayan People’s Liberation Front (TPLF). The TPLF, representing the Tigrayan ethnic minority, ruled Ethiopia for nearly 27 years without political division. In 2018, the election of Abiy Ahmed and the establishment of an Ethiopian federal government of Oromo ethnic origin removed the TPLF from the government sphere. Accusing the Ethiopian government of marginalizing the Tigrayan ethnic group, the TPLF has since stated its objective: fighting against the centralized power handled by Abiy Ahmed in Ethiopia and freeing Tigray. The rebels armed themselves heavily, held independent legislative elections in 2020, and the war was officially started by the attack on a federal army barracks on the night of November 3. Ethiopia has now reached the heart of the conflict between the coalition of the TPLF rebel forces and the alliance of Oromo and Amhara militias, helped by the Eritrean army, which the Prime Minister allowed to intervene.

It is necessary to understand that the federal government and TPFL are not the only belligerents involved; the reality is a much more complex narrative. Ethnicity plays a crucial but not exclusive role in Ethiopian politics, as the country is home to more than 80 different ethnic groups. The ruling Prime Minister is part of the largest group, as the Oromo compose a third of the national population. Next comes the Amhara, representing a quarter of the Ethiopians. Finally, the Tigrean population, which resides mainly in the Tigray region, accounts for seven per cent of the Ethiopians.

However, presenting ethnic heterogeneity in the Ethiopian population is not sufficient to understand the causes of this complex crisis. An analysis of the region’s history is also necessary to explain the embedded obstacles to peaceful settlements. Opposition between the central power and its peripheries has existed since the very formation of the Ethiopian state. This ancient Shoa dynasty, which ended under Menelik in the 19th century, was marked by regionalist insurgencies. In the 1970s, while Ethiopia was ruled by Emperor Haile Selassie I, socialist-influenced movements enabled the rise of a progressive popular revolution. In 1974, the Coordinating Committee of the Armed Forces (the Derg) joined the revolution and overthrew the emperor. Thereupon, a military dictatorship controlled the country between 1975 and 1991.

The Ethiopian military junta pursued centralized control that managed to wipe out all contending political opposition through widespread violence and repression against various communities. Thus, in the early 1980s, the TPLF gained strength and a broad base of popular support. It became a regional liberation movement for Tigray and, with its allies, fought the military equally to take power and to reinvent the conception of the Ethiopian state. Therefore, a coalition of other regional movements with the TPLF created the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF), which overthrew the Derg in 1991 and reformed the country after numerous resurgences. The autonomist and regional parties in the coalition thus drafted the 1994 Ethiopian constitution.

Ethnic federalism is enshrined in Ethiopia’s 1994 Constitution, which states that “every Nation, Nationality, and People in Ethiopia has a right to self-determination, including the right to secession.” Although it is hard to achieve because of legal conditions, this embedded right to secession and federalist rhetoric left a lasting legacy on Ethiopian politics. Today, for Amhara and national elites, ethnic federalism impedes the creation of a strong, unitary nation-state that Abiy Ahmed has been seeking since 2018. Ethnic federalism is not enough of a compromise for ethnonational rebel groups; a peaceful ceasefire could still be an option and a highly desirable one in the eyes of the international community, but it seems unlikely considering the ongoing progress made by rebel groups.

One year later, the crisis has transformed into a disastrous humanitarian situation in the Horn of Africa region, emphasized by the recent escalations of violence. North of Ethiopia, 400,000 people in Tigray live in famine conditions. The Ethiopian government’s efforts to constrict the flow of aid into a region controlled by Tigrayan rebel forces only reduce the likelihood of successful negotiations. Indeed, the government denying permission to trucks filled with food, medicine, and fuel to move from neighbouring regions to Tigray enhanced has only incentivized the TPFL to undertake an aggressive strategy for the TPLF.

In late October 2021, after the fall of two cities close to the capital, the Ethiopian government declared a state of emergency. In a Facebook post since deleted for accusations of hate, Abiy Ahmed called on citizens to arm themselves. Such a message was conveyed as the United Nations released a report on the region, which depicts the violence of the conflict as having forced more than 1.2 million Ethiopians to be displaced. Evidence is mounting of human rights violations by both sides, particularly reflecting numerous abuses against women. The conflict has resulted more broadly in violence against all civilians as thousands, whether Tigrayans considered traitors by the TPLF Amhara civilians or enemies of the central government military forces, have been killed.

Finally, in late December 2021, Ethiopia witnessed a new turnaround in the situation caused by an increase in the strength of the federal army. The government announced the non-advancement of troops to Tigray, giving hope to the international community of open negotiations. However, the situation has recently fallen back into extreme violence.

The legacy of historical secessionist movements, the horrors committed since the beginning of the conflict, and a society based on ethnic federalism make the incentives for a diplomatic resolution extremely limited. Even worse, the latest government messages promoting violence to permanently destroy the TPLF justifiably worries experts about giving rise to “the expansion of combat operations and intercommunal violence.” The airstrikes witnessed in December 2021 correspond to more preemptive government military actions rather than negotiations. These attacks have left a bitter taste to Abiy Ahmed’s Nobel Peace Prize, as the Prime Minister seems unable to resolve the Ethiopian civil war.

Featured image: “Ville gens rue banniere” by Brett Sayles is licensed under Pexels.

Edited by Joshua Poggianti