The Murray Darling Basin Plan: Exposing Australia’s Own Watergate

In 2012 the Gillard Government signed the Murray Darling Basin Plan (MDBP) into law. The Plan, as envisaged by former Prime Minister John Howard, set out a holistic framework for equitable water distribution, ensuring communities, industries, and local environments are well sustained. Since then, the Plan has battered river communities, severely weakened local supply chains, and has left many locals with a sense of hopelessness for what the future within the Basin holds.

Imagine being a farmer standing over the banks of the inundated Murray River as it flows downstream past your dry, parched land. Even worse, imagine not being allowed to take even a single drop from that river. This is the case for farmers right across the Murray-Darling Basin area, despite the drought continuing to subside. Imagine being that same farmer now, watching from afar as supermarket shelves are stripped bare of staple foods as the coronavirus pandemic rages, while still struggling to sow a single seed. With global supply chains ruptured due to quarantine measures, light has now been cast on Australia’s current food supply, and whether there is enough to feed the nation. Although the Federal government has reassured Australians that food scarcity isn’t an issue, one bureaucratic policy continues to serve as a thorn in the side for Australia’s food security and desperate farmers—The Murray Darling Basin Plan.

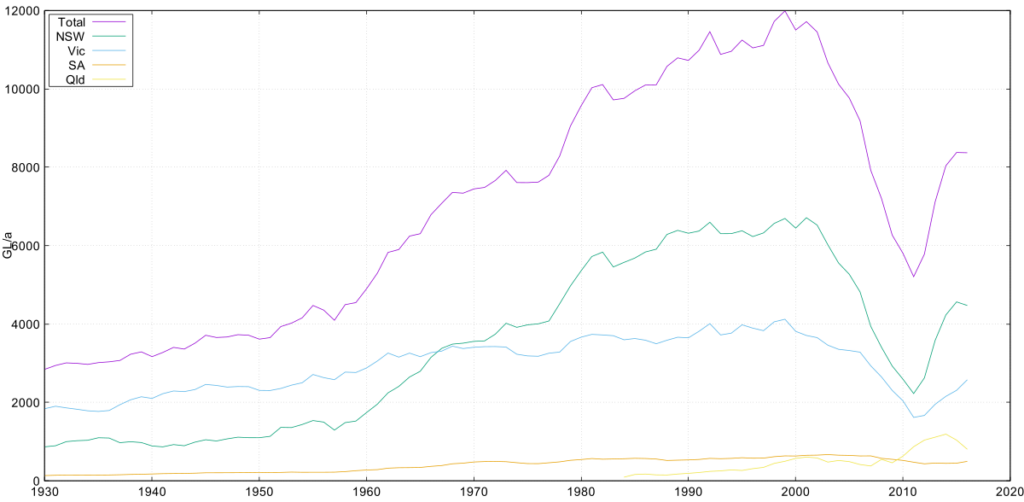

The MDBP serves as a strategic instrument that provides a national framework for water control over one-seventh of the Australian continent. The Basin accounts for roughly 40 percent of Australia’s agricultural productions—essentially making it the lifeblood of Australia’s food supply. However, in recent years the MDBP has undervalued the importance of a productive agricultural system, instead wasting gigalitres of water downstream. Just two years ago, the Southern Basin was producing approximately 60 percent of the nation’s food supply. Since then, the region has seen farm closure after farm closure due to inadequate water allocation and drought. This is despite the Murray-Darling River Basin storing enough water to provide relief, regardless of drought. Now, once-thriving water-dependent communities are experiencing economic volatility, sharp falls in investments, and uncertainty over the region’s future.

This imbalance of water allocation underlines the intricate nature of the Basin policy and its broader social implications for the region. To add salt to the wounds of already struggling farmers, one key objective of the plan is to remove over 2,500 gigalitres of water from the river system to maintain the health of the Basin’s environment. This is otherwise known as the sustainable diversion limit (SDL). The policy’s imbalanced approach is indifferent to the objectives and aims stipulated under the Water Act 2007. Section 3(c) of the Act requires ‘the use and management of the basin water resources in a way that optimises economic, social and environmental outcomes.’ Additionally, the SDL is required by the Act to be set based on “best available scientific knowledge.” In 2011, a group of leading scientists appointed to help develop the MDBP pulled out due to serious flaws in its direction. The scientists were concerned that the disproportionate allocations of water would severely impair key parts of the river system. It is clear that the MDBP’s objectives fall short of addressing the economic and social outcomes under the Act, given the dire situation within the agricultural sector and local communities. The pains of the MDBP are now being felt in political circles such as the New South Wales Parliament. In December 2019, NSW Nationals leader John Barilaro warned that “we simply can no longer stand by the Murray-Darling Basin plan in its current form, the plan needs to work for us, not against us.”

A balancing act or a mechanism for disparity?

In 2018, both state and federal governments agreed to ensure that water would be allocated to the environment, provided it did not result in adverse conditions for river communities. However, since this agreement was made, the SDL has been adjusted to hold up to 2,680 gigalitres of water to maintain the Basin’s surrounding environment. Even worse, there is a mechanism available in the plan that allows Basin authorities to reallocate an additional 450 gigalitres of water to the environment under the guise of ensuring it has a “neutral or improved” impact on river communities. This term has been subject to scrutiny by both farmers and bureaucrats given the ambiguity of its definition. Despite the lack of transparency behind many parts of the plan, there’s no refuting the fact that the MDBP has denied the livelihoods of farmers and surrounding river communities due to lack of water accessibility, In fact, the actions of the policy may have contravened the Water Act 2007. Amidst the coronavirus pandemic, the spotlight has shone on Australia’s agriculture industry, and by extension, the deficiencies of the MDBP.

With global trade now grinding to a halt, there is no better time to address the MDBP. The eyes of Australians will now turn to farmers delivering essential foods such as rice and wheat as we ride this crisis out. The pandemic will also challenge Australia’s food security, and expose our high dependency on global imports. Farmers are urging the federal government to release additional water to support Australia throughout the crisis. 13 bodies representing irrigators and river protection groups have signed an open letter to the Prime Minister asking for the government to sidestep the MDBP and take swift action on water releases as it is critical Australia safeguards its food security. It’s a simple matter of ‘just add water’.

Conclusion:

The unlawful predicament imposed on farmers has created a water emergency within the Basin area. All these issues could have been mitigated (or outright avoided) if it wasn’t for poorly guided bureaucratic interventions and flawed science. The MDBP has been a failure of staggering proportions, amounting to a fraudulent scheme at the expense of Australian taxpayers. A Royal Commission should be formed to investigate the Plan in its entirety. With the coronavirus threatening Australia’s food supply, the timing could not have been worse. Successful action investigating this fraud will require auditors to investigate the plan in its entirety.

Featured image “Murray-Darling Basin Map” under license CC BY-SA 4.0.

Initially published in the Kosciuszko Review, this article is published in the MIR through a collaboration between the two publications.