The Price of the “Olympic Spirit”: The Economic and Social Costs of the Olympic Games

The Olympics are upon us, and with the opening ceremonies on August 5th, the games have promptly begun and will continue until August 21st, showcasing the world’s top athletes. Nations will come together and forget about current transgressions, substituting conflict for the grand concept of the “Olympic spirit” – or so is the contemporary global narrative. For others, the Olympic Games can be a tiresome exercise in nationalism, sidestepping the strife of the oppressed or struggling people of the host country or of those around the world. Before I go further, I want to state that I consider myself a big fan of sport. I was a competitive swimmer for years, as well as a coach shortly afterwards, so I understand how much it must mean to someone to compete at a level as high as the Olympic Games. That being said, the games have never been without controversy, and have often proved to ultimately be a cumbersome process with minimal benefit in terms of social and economic costs, often proving negative long-term effects.

When thinking of long-term economic effects, Greece is one country in particular that comes to mind. Currently in extreme economic turmoil (partially also due to the austerity regime of the Troika), Greece (with Athens as the host city) hosted the 28th Olympiad in 2004, amounting to a whopping price of 9 billion euros, the most expensive games ever at the time. This came briefly after Greece had weathered a period of austerity to qualify for the adoption of the euro, so money was already tight regardless of whether the games had been there or not. Despite that fact, as a result of the “Olympic spirit” and eventual entry into the euro, the purse strings were loosened and with an already ballooning public debt of 168 billion euros, the Olympics were funded by unsustainable borrowing. Infrastructure that once hosted world-class athletes lay unused and derelict. While the games themselves are not the main reason behind Greece’s recent economic hardship, they are a good example of the systemic economic problems facing the country today, and also a good example of how the Olympic games can steer infrastructure investment into the wrong direction. And Greece is not the sole example: one can also look to Beijing, as well as the recent World Cup in Brazil, where a soccer stadium that can host 40,000 is home to a second-division team that only draws 1500. This constant shift of infrastructure spending for host cities to Olympic venues is hurting their economies, taking capital away from projects of possible greater importance.

Brazil is also facing huge economic costs, with the state of Rio De Janiero having had to declare a financial emergency in June. The state of Rio is facing its worst financial recession since the Great Depression, as well as a period of political turmoil which saw former left-wing president Dilma Rousseff ousted and replaced with the controversial and unpopular Michel Temer, who has been accused of imposing authoritarian rule. In a controversial ordinance, Temer dissolved the Ministry of Women, Racial Equality and Human Rights and gave its functions over to the Ministry of Justice. However, in the new structure of the Ministry, there is no citation to women, racial equality or human rights, signaling that the Olympics are given more importance than human rights under the new regime. The high price tag along with political tension led Brazilians to hold anti-torch relay protests where they attempted to extinguish the flame on its way to the Olympic Stadium. These protests were quashed by the increased militarized police presence (as a result of higher security for the Olympics), resulting in the injury of a ten-year old girl who had been reportedly hit by a police projectile.

According to a report by Amnesty International, police killings in Brazil have seen a surge, with 11 people dead in the month of April alone. According to the report: “the majority of the victims of this recent “surge” in police brutality have been young, black men from favelas and other marginalized areas.” In addition, a few months prior as a result of the World Cup in Brazil, there was an increase in

displacement of people due to new infrastructure projects for the event; a report from Dundee University and Pontifical Catholic University of Rio claimed that several street children had been removed due to “social cleansing” operations. Although athletes and foreign spectators face certain dangers like the Zika virus or contaminated waters, it seems as though Brazillians (more specifically those living in favelas) have the most to fear, according to the report. There is no direct way of linking the killings to the Olympic Games but Amnesty points out that there is a clear correlation, with Rio expected to use twice as many police as London did in 2012.

With increased police presence during the Olympics (Brazil’s own police force was increased by 33 percent), there is not much room for civil dissent, and those deemed to be disturbing the games could face harsh consequences. For example, four years ago in London, according to the Guardian, the UK saw the biggest mobilisation of military and security forces since the Second World War. This came at a time of severe civil unrest in London, when the people of the city were also facing significant welfare and housing benefit cuts. The Guardian also cleverly points out that more police were mobilised during the London Olympics than were in Afghanistan during the time. The same was true for Beijing in 2012 and for Athens in 2004.

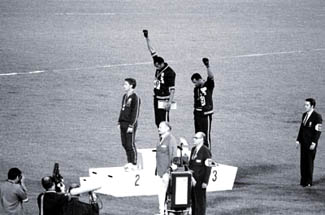

The quashing of political dissent and activism manifests itself in many different ways during and after the Olympic Games, not just in the form of police violence. One prominent example that comes to mind is during the 1968 Mexico City Olympics, when African-American athletes, John Carlos and Tommie Smith, raised their fists clad with black gloves in solidarity with the Black Panther movement while on the podium. Most don’t remember the third man on the podium, white Australian Peter Norman, wearing a button that read “Olympic Project for Human Rights,” an organization set up to oppose racism in sport. All three athletes were scrutinized and banned from competing at the Olympics for life by their respective countries. No one, however, really expected the protest from Peter Norman.

Australia had been struggling with racial tension, trying to implement its “White Australia” policy which entailed putting heavy restrictions on non-white immigration into the country as well as several anti-indigenous laws including taking indigenous children at birth and giving them to white parents (a policy akin to the Sixties Scoop policy in Canada during the 1960s where the Canadian government implemented a virtually similar policy). Norman was not expected to come second in the 200 meter final against the two American athletes, but his actions on the podium changed his life forever. Norman was the fastest sprinter in Australia and among the top in the world, but was not allowed to qualify for the Munich Olympics four years later and then retired from running in disgrace. In the 2000 Sydney Olympics, his nephew, Matthew Norman explains, “he was not invited in any capacity.”

The Olympics seem have often been a way for nations to bolster their national image, resulting in the shunning of anything that could get in the way of national pride. The most

prominent example of this are the 1936 Olympics in Berlin, of course, where the city was adorned with Nazi flags and national pride, while anti-Semitism and racism ran amok as the world and the IOC turned a blind eye. Avery Brundage (IOC president during those Olympics) opposed a boycott and noted that the Olympic Games belong to the athletes and not the politicians…” effectively suppressing dissent and saving the “Olympic Spirit” at any cost.

Finally, the Olympics also prove to be a huge hindrance to labour standards as well. This has been quite clear in Brazil from claims of workers having lived in conditions akin to slavery to the outright violation of human and workers’ rights. The Toronto star notes that: “leading up to the Games, host countries are supposed to honour Olympic pledges…but they aren’t held to them. Repressive countries renege, and they count on the international bodies to ignore it.”

Even though the Olympics have traditionally been an event surrounded by elitism and marred by claims of human rights violations, they don’t have to be. In Sweden’s bid for the 2022 Olympics in Stockholm, they have made an historic labour deal with the Swedish Trade Union Confederation, with the agreement guaranteeing “union organising and collective bargaining rights, non-discrimination and freedom from forced labour and child labour.” This was in response to the overuse of migrant workers in construction projects for high profile sporting events like the 2022 FIFA World Cup that will take place in Qatar (see one of my past blog posts). Additionally, a coalition of NGOs and labour unions (the Sports and Rights Alliance), wrote to Thomas Bach (president of the IOC) to “recommend that the IOC includes labour and human rights standards in the 2024 Olympic Host City contract.” Moves like these can help improve the Olympic Games so they do not continue to be a byword for oppression.

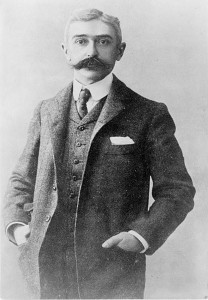

The Olympic Games are many things: spectacular, exciting, a chance for nations to come together, and a once in a lifetime chance for

athletes who have worked their entire lives for that one important moment. However, they are also a continuing example of human rights and labour violations, elitism, and nationalistic bias. It is time to change the games, and actually make them an opportunity to, as Pierre Coubertin (the founder of the modern Olympiad) writes in his poem O Sport, You Are Peace, “forge happy bonds between the peoples.” It is time that the Olympics become a space where universalism trumps nationalism and the rights of all, poor, rich, labourer, or athlete, can be respected.

In Solidarity,

Sam