The Taliban: Looming Kingpins of Afghan Opium

An opium poppy post-harvest.

An opium poppy post-harvest.

What the Afghan government and other actors hoped would be a period of stabilization and decline, or at least stagnation, turned out to characterize a continuous and tremendous upsurge in the country’s notorious opium production. In 2017, Afghanistan’s opium production hit record levels, rising 87 percent compared to the previous year. What is paramount though, is that the group reaping an increasing amount of the proliferation happens to be one of the world’s most feared insurgent forces.

Opium: A national health crisis

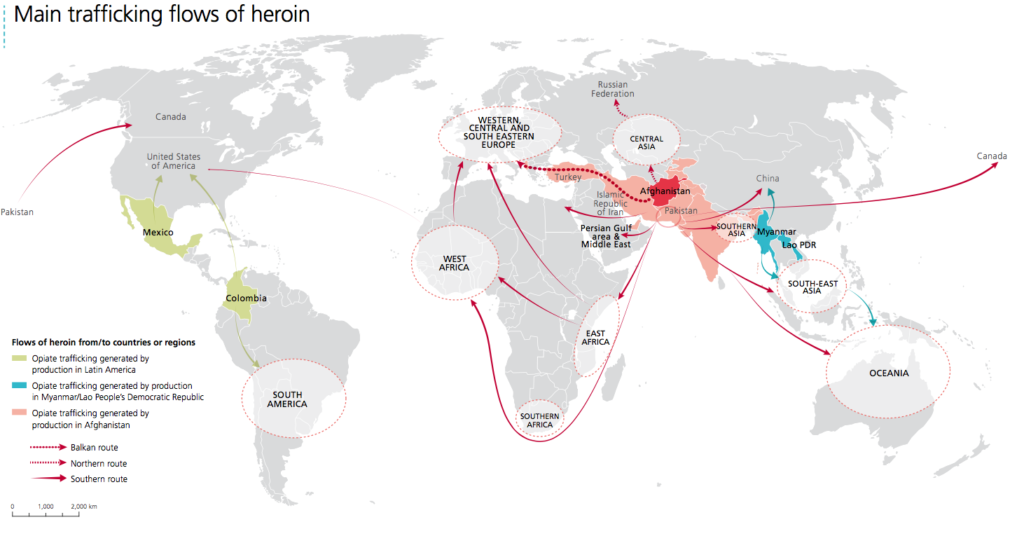

Earlier, opium would be smuggled out of Afghanistan unrefined, but now more than half is domestically processed into morphine or heroin. This makes it easier to smuggle through trade routes both inter-provincially and internationally. Afghanistan is currently responsible for 80 percent of the world’s opium supply. The drugs are directly trafficked to Iran, Pakistan, and Central Asia, from there, they are transported to the rest of the world. A smaller portion of the heroin in the U.S. can be traced back to Afghan production, but significant portions of European and Canadian supplies – over 90 percent of heroin in Britain and Canada – comes from the growing narco-state. As the problems abroad are exacerbated with the increase in cultivated areas, so are problems at home.

Afghanistan is cemented in a drug war, where right now, there is no winning side. Over 2.9 million Afghans are involved in opium production, which accounts for over 12 percent of the population. Most of the work is concentrated in the southern Helmand province, where about 80 percent of the country’s poppies are grown, and clandestine morphine and heroin labs prevail. Helmand has also been the leader in investing in advanced agricultural methods. They’ve developed special fertilizers and pesticides, and have adopted the use of solar panels for irrigation pumps to make sure they are able to produce opium efficiently, even under inconvenient conditions. The farmers behind the cultivation process are drawn to these illicit livelihoods only because opium is far more beneficial than other crops like wheat; it sells at a much higher price, and can also be stored and used as an investment for several years. Combined with local factors like poor education, little employment opportunities, and limited access to markets and financial services, people in rural areas are compelled not by any drug cartel, but by the basic necessities of survival.

Apart from production, Afghan opium is largely conducive to drug addiction problems. The UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) in their 2015 Afghanistan Drug Report report, estimated that there are between 1.9 and 2.4 million adult drug users in Afghanistan, alone. This figure has likely risen and not to mention, does not include adolescent users or children who have regular secondary contact. The situation for treatment is abysmal. Medical professionals use a cold turkey method; addicts are left to find emotional comfort only amongst themselves. There is a total of only 70 spots in clinics in Helmand, none of which are for women. Recently, females are becoming especially prone to addiction in such regions. They have increased access, and use the opium high to escape the many hardships that are imposed upon them. In turn, this affects the entire family unit because of their central role in domestic life. However, even if treatment is a viable option, women risk being shamed by their society if identified as an addict. The opium trade has left its mark in all places of Afghan life.

The Taliban: Insurgency group or drug cartel?

This is why the increasing involvement of the Taliban is so troubling. Profits from the drug trade are now making up more than 60 percent of the terrorist network’s total income, with at least $200 million of the opium industry going into their hands. More and more senior Taliban leaders are beginning to take larger and more direct roles within the business, making it hard to tell whether the Taliban is a terrorist group or a drug cartel. They’re involved at every stage of the process. In areas where there are few refining labs, they have created their own, as close to the poppy fields as possible. They continue to tax farmers and provide security to smugglers and producers, but now use their own “drug factories” to profit from the sales and trafficking of morphine and heroin, two significantly more expensive opioids. Such enticing economic incentives minimize the chance that the Taliban will move towards peace talks and reconciliation with the government. Towards the latter half of the year, Taliban resurgence revealed a new tactic of blowing up police and military bases; one can guess where the funding for explosives came from. It is estimated that 45 percent of Afghan districts are now contested or controlled by Taliban forces, corresponding with a 5 percent decline in the amount of government-controlled territory in 2017.

As the United States continues to wage its longest war in history, its forces are employing both counter-terrorism and counter-narcotics efforts. The Trump administration now allows the Pentagon to target Taliban revenue sources, which is unlike previous programs where it would only act preemptively or directly with Afghan forces. In November, the U.S. military conducted airstrikes targeting labs in the north part of Helmand, where the Taliban had a stronghold. The Afghan president, Ashraf Ghani, is on board with the new campaign as well, expressing his determination in tackling “criminal economy and narcotics with full force”. Overall, there was little attention from the Trump administration on the opium trade through the year. When the President announced his new strategy in August, the opium issue was not brought up once, even though it was announced in June that almost 4,000 additional troops would be sent in. The military, however, is clearly taking steps forward.

Stopping a relapse

Is blatant extermination really the best solution? The poppy farmers themselves disagree. Destroying the factories would affect ordinary people and their ability to generate income more than it would hinder the Taliban. They also know that labs are easily replaceable and can be built in a few days. Analysts from the Kabul-based Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit called it a futile game of “whack-a-mole”; it’s been tried and failed before. Finding the effective solution cannot just be a “band-aid” effort; a lucrative business that took decades to expand will not be taken down with a few bombs. If Ghani continues to support eradication methods, it will only drive more farmers into destitution, and leave them susceptible to Taliban manipulation. Thus, it will perpetuate a terrorist-controlled drug network that fuels anti-government and anti-American sentiment among civilians.

Internationally, a stronger Taliban will worsen tensions between Afghanistan and her neighbors. Saudi Arabia supports the U.S. plan and the Afghan government, yet many influential tribe leaders funnel money into the hands of the Taliban. This juxtaposition is unstable especially in the face of a proxy war with Iran over Lebanon, which has a significant influence in Western Afghanistan. Not to mention, the greater supply of low cost, high-quality heroin to consumer markets around the world means more consumption and addiction harms. From the Taliban’s present success, it’s expected that their capabilities will become more extensive; their alternative sources of revenue are nowhere near as remunerative.

Afghanistan’s severe economic dependency on the opium trade will make it extremely difficult to successfully make the transition from illicit to licit methods. In addition, corruption within the government means resources are enmeshed with the criminal business, as some officials derive income from the trade themselves – their mansions are referred to as “poppy palaces”. Not only does this further strain the government’s ability to distribute crucial public health services to those needing addiction treatment, but it also perpetuates the poppy cultivation further. No one seems to be considering the threat of environmental damage either; with such rapidly manifesting crops, overexploitation will come fast and with harsh ends for poppy farmers and workers.

The steps that stakeholders need to take in order to fix the opium crisis go beyond the poppy fields. Other than simple eradication, the legalization method would also be ineffective as it is heavily contingent on security, which Afghanistan clearly does not have a convincing amount of. Development based approaches, including crop substitution, need to be emphasized. The alternative development (AD) program endorsed by the UNODC, which comprises of interdiction and eradication as well as human development, needs adequate economic means and political determination to prosper. There is too much focus on drug production, and not enough on its motivators.

Afghanistan will have to solve the socioeconomic and political causal factors in addition to promoting legal alternative crops, so that the millions who rely on the opium trade will be able to maintain subsistence. The U.S. on the other hand, will need to deconflict its counterinsurgency and counter-narcotic efforts. The Taliban threat and the perils of the opium trade go hand in hand. Getting rid of one will lessen the threat of the other, but both require distinct procedures, and immediate action.

Edited by Sarie Khalid